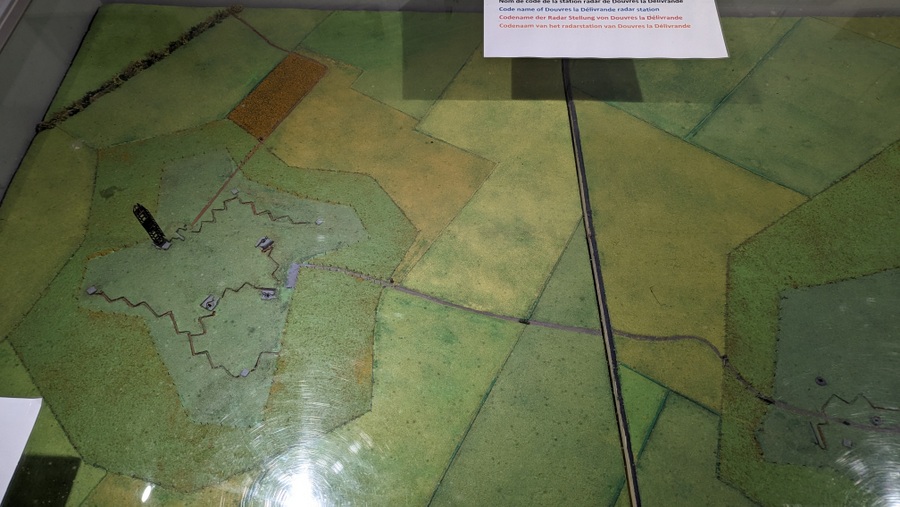

The Radar Museum 1944 is on the site of the Germans’ largest radar station in the Calvados region of Normandy. The original top-secret site covered a huge 10 hectares on the plateau outside the town of Douvres*. However the museum and its bunkers cover only a small part of the site.

D-Day Normandy Posts

RADAR History

The tale of the ‘Battle of Britain’ has led many to think that the British invented radar and that British radar was the most advanced. Not entirely true. In fact the story is a complex one, not least because of the secrecy surrounding it and the way in which different scientists came at the problem from different directions.

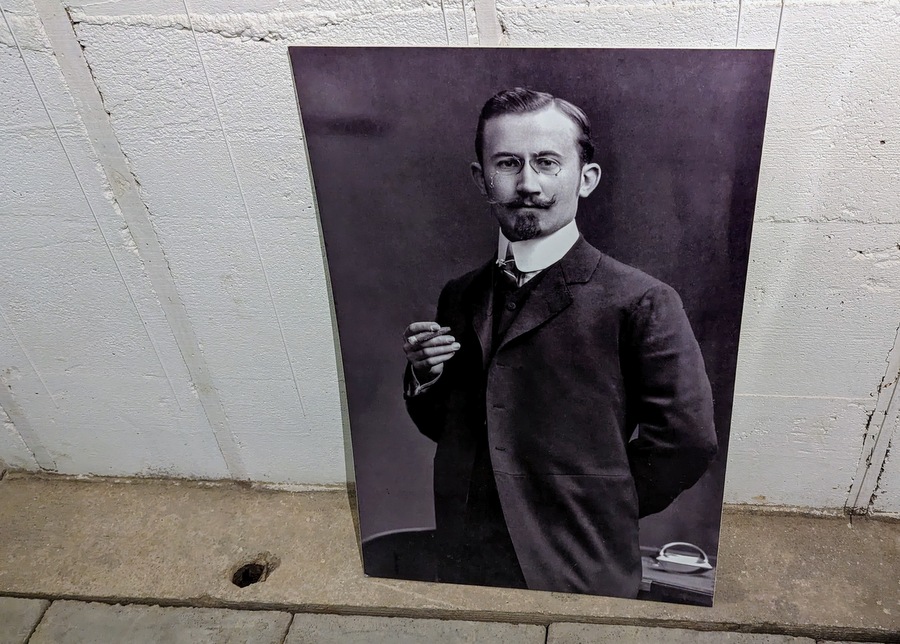

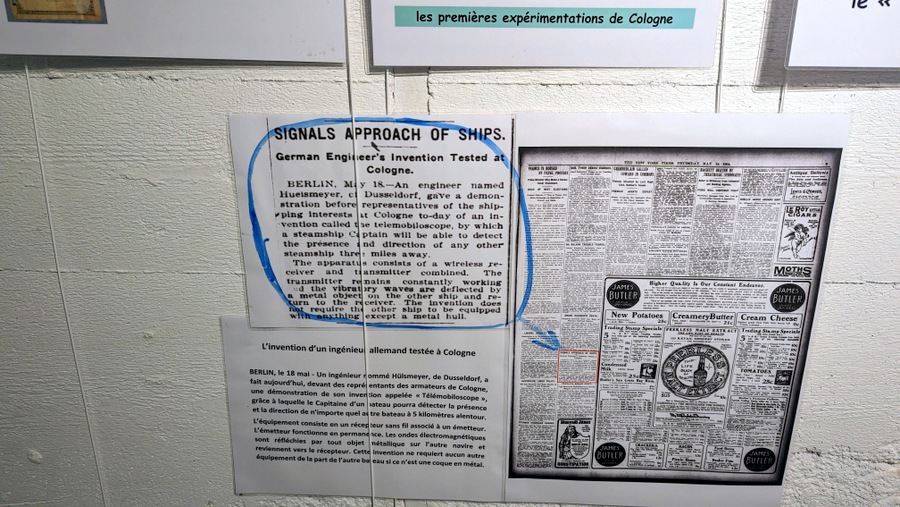

That said, it’s widely agreed that the first person to show that electromagnetic waves could be reflected was the German physicist Heinrich Hertz in 1887, and the first to develop the idea into a practical device was another German, Christian Hülsmeyer, who in 1904 demonstrated his telemobiloscope which could detect ships 3 miles away.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that the British scientist Robert Watson Watt began to make progress on the concept, eventually leading to his first successful aircraft detection and ranging experiment in June 1935. He called it Range and Direction Finding (RDF). It was the United States Signal Corps who came up with the name RADAR (Radio Detection And Ranging) in 1939.

Meanwhile the Germans were moving ahead with their radar technologies and had developed a number of sophisticated land based radar systems for detecting aircraft by the time war started. At that point, Britain’s ‘Chain Home’ radar network was not the most technically advanced, German radar was more accurate, but was not being used effectively. There was no strategy for its use. Hitler was really only interested in offensive weapons. If this new fangled radio tech could be turned into a beamed death ray, Hitler would have supported it!

British radar, on the other hand was ALL about defence. It might not have been as advanced as German radar, but it came with the most sophisticated reporting and directing system for command and control of RAF fighter defences** – that was the tale of the ‘Battle of Britain’.

It was time for the Germans to catch up. When Hitler cancelled Operation Sealion (the invasion of Britain), German priorities switched from offensive to defensive structures and technologies – the Atlantik Wall and Radar. Radar stations started appearing all along the coast of Europe and Scandinavia.

The Germans had three main radar types…

The Siemans FuMG 402 Wasserman radar looked similar to Britain’s Chain Home transmitters & receivers***; 65 metre tall, fixed masts. It was a long range early warning radar. It could detect aircraft at 380 kms flying at 20,000ft. 150 of them built.

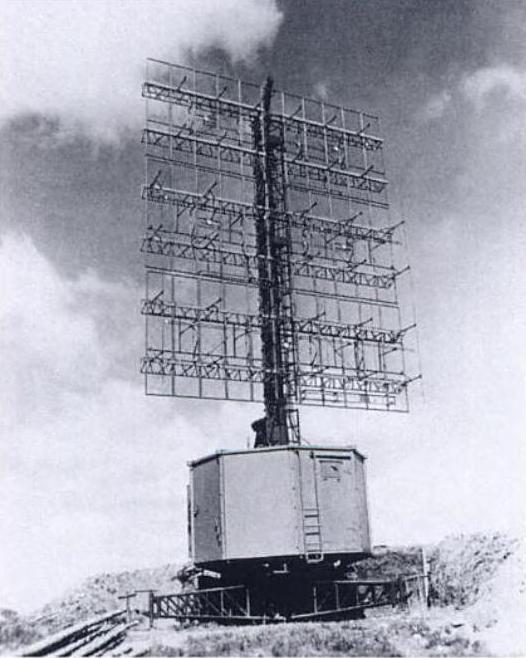

The Telefunken FuMG 80 Freya was a mid range early warning radar with a range of between 150 – 200kms. It had a moveable lattice frame. 1,000 units were built. Some were adapted for use by the navy.

The Telefunken FuMG 65 Würzburg Reise was a tracking radar with a horizontal and vertical 7.5m radius moveable dish. Range 80 kms. 1500 were built.

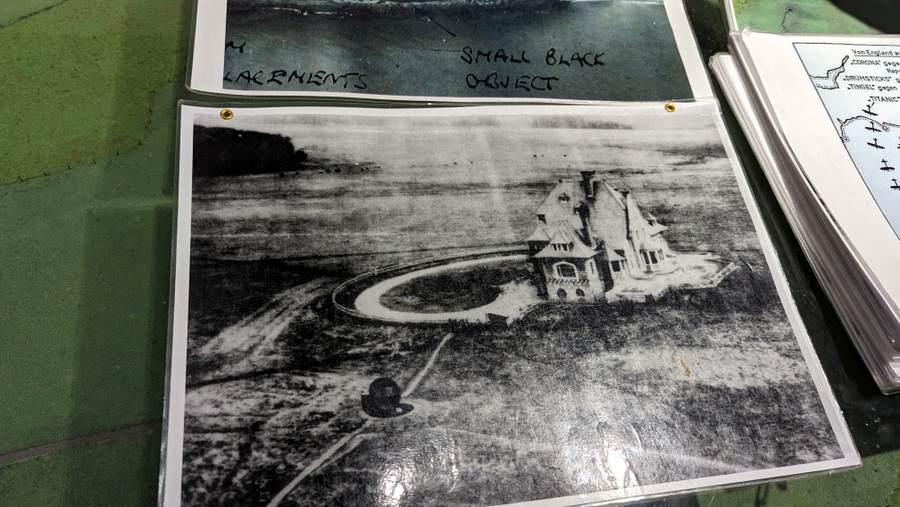

The variety of radar units must have alarmed the British because they put a lot of effort into photographing and investigating them. The ‘Bruneval Raid’ is an example. A photo-reconnaissance Spitfire spotted a strange dish (Würzburg Reise) on the coast at Saint-Jouin-Bruneval between Le Havre and Fecamp on 5 December 1941.

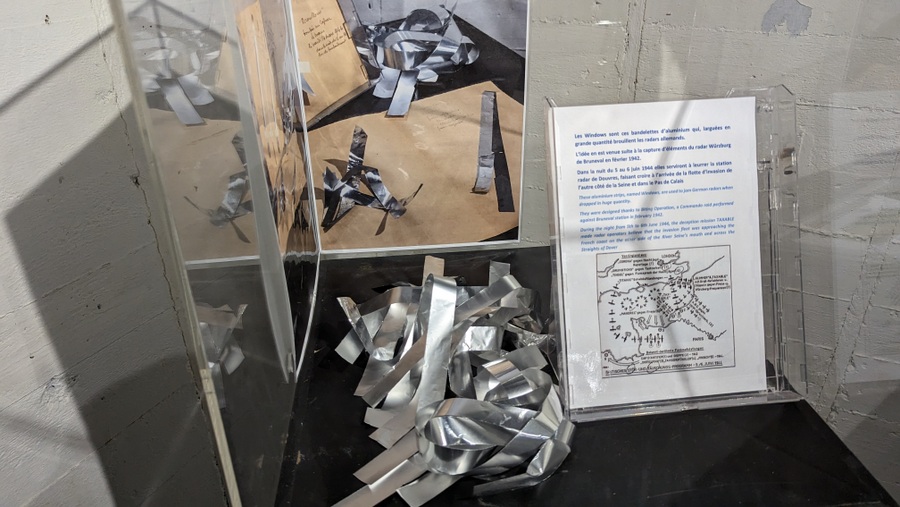

A few weeks later, in February 1942, an airborne commando force was sent to assault the site and seize the technology. They took an RAF technician with them to identify and dismantle the key components (receiver, transmitter, amplifier, pulse generator, and operation manuals). The raid was successful and the British learned how some German radar worked and were able to develop methods to counter it. The introduction of ‘Windows’, the aluminium foil strips dropped from the air to confuse German radar was a result of the intelligence gathered on this raid.

Douvres Radar Station

The Luftwaffe began planning the Douvres Radar Station about the same time that Bruneval was raided. The location, 50 metres above sea level with flat land all around, few trees and a panoramic view of the sea, made it ideal for a master radar station, not a minor sub-station in the network. It was code named Distelfink (Goldfinch).

By 1944 there were 92 radar stations housing between three and four hundred radar units between Dunkirk and Ushant at the west point of Brittany. Only six of these were master stations. Distelfink was one of them.

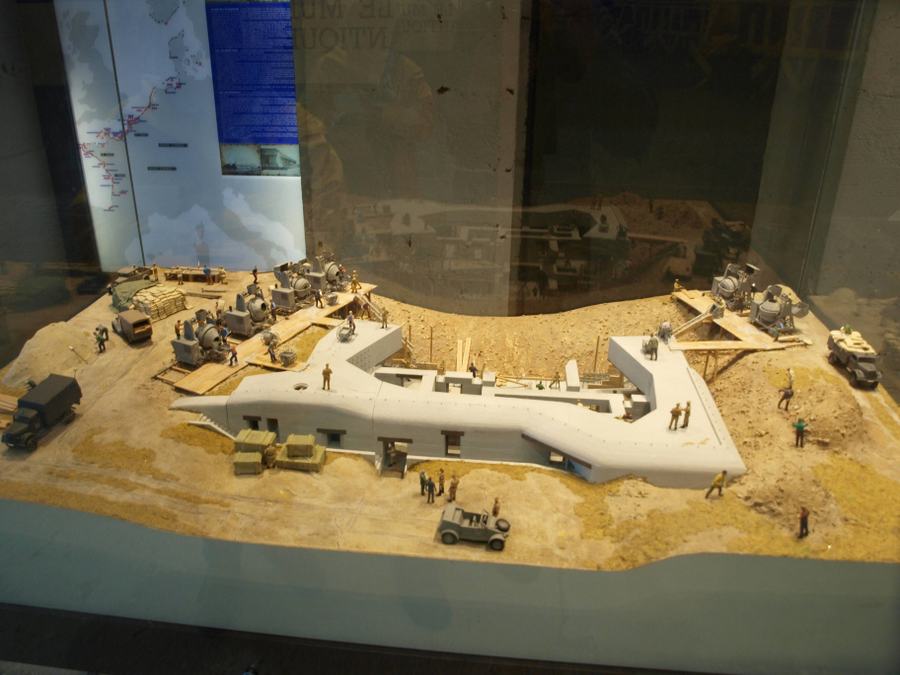

When work was completed by the Todt Organisation in late 1943, it had two sectors separated by a country lane. The northern sector housed a long-range Wassermann mast. The southern sector had two Freyas and two Würzburg Reise dishes. The whole station had 30+ bunkers including tobruks and mortar positions, kilometres of trenches and barbed wire, mine fields, 20 x machine gun nests, 7 x 20 and 37 mm flak guns and 6 x 50mm & 75mm anti-tank guns.

In the weeks leading up to the invasion, many stations in the German radar network were bombed. The bombing was spread out across France so as not to draw attention to Normandy in particular. Distelfink was mostly spared, but it made little difference on the day because the Allies either jammed or deceived the entire German network from the Pas-de-Calais to the tip of the Cotentin peninsula. In particular, the precision navigation skills of the famous 617 ‘Dambusters’ Squadron were used in Operation Taxable to make it look like a large fleet of ships was heading for Cap d’Antifer at 8 knots by dropping steadily advancing clouds of metal foil (‘Windows’) in relays. Meanwhile 218 Squadron’s Stirling bombers were doing the same in the Dover Straits (Operation Glimmer).

When dawn came on D-Day, bombs and naval shells rained down on the station. All five radars on the site were either destroyed or heavily damaged. The station may no longer have been operational, but it still had formidable defences and a determined garrison of 238, who fought off all attempts to capture it in the first few days of Overlord. In fact it became a thorn in the side of the Allies who had surrounded the base and were now advancing on Caen. From its elevated position, the station could see where the enemy was and report their positions and movement.

Something had to be done, not least because it now also threatened Advanced Landing Ground (ALG) B4, one of the many ALGs being quickly set up to operate the tactical air force Typhoons and Spitfires. ALG B4 became operational on 15th June, right next door to Distelfink with its AA guns! So, on 17 June British armoured forces (using AVRE flail & mortar tanks) and Royal Marines stormed the base.

The Radar Museum

The Radar Museum tells not just the story of the site itself, but also the history of radar up to 1944 and into the Cold War era. It also talks a little about the station in relation to the local community.

Museum Director, Philippe Renault, says there was a pretty easy-going relationship between the locals and the German garrison. This was a Luftwaffe base, and so they interacted with the locals in ways that, for example, the SS wouldn’t. They would pay for food and services and generally treat the locals with respect. In some ways that might have been a mistake. For example the local postman used to make a 3 kilometre daily trip on his bicycle to deliver & collect post between two villages which were on either side of the radar station. Suddenly it became a 5 km ride around the base, but the base commander relented and gave him permission to cycle through… a top secret base!

It seems the base commander was a bit of a push-over. The mayor of Tailleville, a village on the edge of the base had noticed that he was particularly fond of lilacs. On the day the base became operational, he cut some lilacs and took them to the station gate as a congratulations gift for the Commander… who let him in! Of course much of what the postman and the mayor saw found its way to the local French Resistance.

The Museum occupies 3 hectares in the southern sector of the 1944 10 hectare site. There are a number of bunkers here, including the radar station’s control centre and command post bunker, plus the Würzburg Reise dish and a scaled down recreation of a Freya.

There is a natural route (gravel path) around the site which starts and ends at the ticket office/shop. You can explore it yourself using their free audio guide on your phone, but there are also guided tours at certain times of the day (see factbox).

Type 622 Bunker

There is an H622 (20 man barrack) bunker immediately behind the ticket office and this is where the tour starts. Inside there are some historic photo displays relating to the local area, and some explanations of what the station did and what kind of radars it operated. There’s a large model of the station (too big to get in a single photo) that shows how big the station was and how well defended.

Other Bunkers

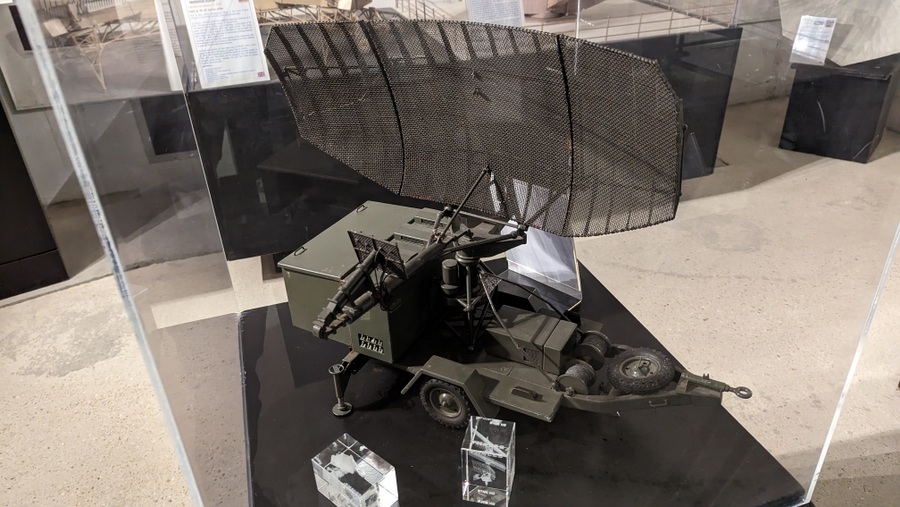

The path passes an Cold War era airfield radar unit and two large bunkers that are not (yet) open to visitors.

The first is another H622 barrack room bunker with a ‘tobruk’ machine gun position on the top.

The second is the power plant for the base.

Unusually, it is not made of reinforced concrete, but mostly of stone blocks. The reason was, it was quicker to build so the generators could be supplying electricity to the rest of the site as they built it.

The Würzburg Reise radar

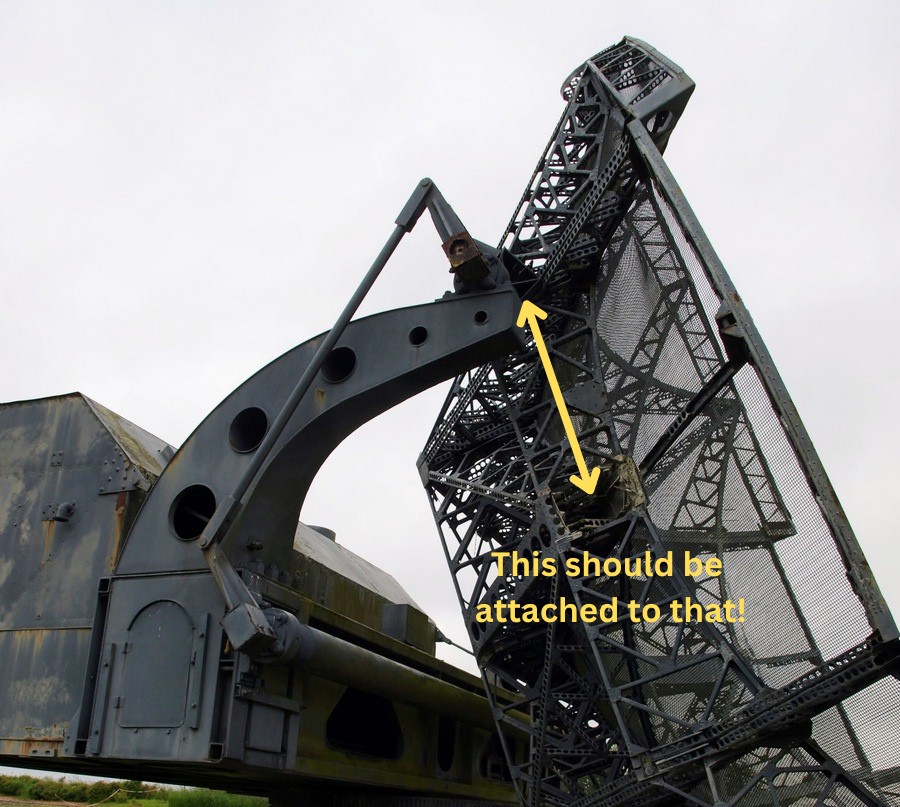

By the end of D-Day all the radars on the site were destroyed including the two Würzburg Reises. This rare example was actually one of three intact Würzburgs captured at the end of the war.

In 1957, two of them were repurposed for radio astronomy and moved to an observatory near Orléans, where they worked on interferometry experiments for a couple of years. In 1991 the observatory donated a, by now very dilapidated, Würzburg to the Douvres museum, which opened in 1994. A lot of work had to be done to restore the radar, which had corroded badly, to a respectable condition.

Unfortunately the site is exposed to all weather conditions and the corrosion continues. The dish support arms collapsed in strong winds in 2017 and the dish literally fell off – there’s a photo of it lying face down. Since then it has been sitting propped up, and awaiting the funding needed to repair it.

There is a restoration plan, which could be helped of course with more visitors.

Control & Command Bunker

The Type L479a (“Anton”) bunker is a “Funkmessgerät Auswertung” (Radar Plotting) bunker***. It’s a large bunker with 20 rooms built on three floors and buried deep. This is the core of the museum.

There are some really interesting displays in here, starting with a cutaway model of the bunker showing just how large and complex it was.

There are also a set of display panels covering the development of radar and key advances like the magnatron. In the same room are a set of models of different types of radar developed and used by the Germans, British and Americans.

In the centre of the bunker is the 2-storey plotting room with a balcony overlooking the two Seeburg plotting tables – frosted glass maps onto which beams of light where shone from underneath, showing the tracked position of friendly and enemy aircraft. It’s an interesting contrast with the RAF plotting tables. We pushed markers around a map table with stick… the Germans shone coloured lights from behind.

On the wall in the plotting room there are some extremely rare photographs – given that these were ultra top secret facilities – of Luftwaffe staff working in plotting rooms in other L479 bunkers.

In the room next to the plotting room, where ancillary plotting staff worked, the museum has set up a giant wall map where you can see the huge network of radar stations facing each other in England & France. There is a circular short movie that tells more about the site and its role, and a glass floor looks down into the barrack room below.

Downstairs you can see that barrack room with its bunk bed, heater, table and personal items, left as if the men who worked here had just gone outside for a smoke or something. Next to it are the operators who control the light markers on the Seeburg plotting table, and their equipment.

Then there are a couple of galleries that focus on the early pre-war and post-war versions of electromagnetic detections systems. The early radar room has some photo displays of the early pioneers and their achievements, and some display cases with early valves and magnetrons – the invention that ramps up the power and frequency of a transmitter… and powers your microwave!

In the post war gallery are displays and models of Cold War radar devices.

Also on this basement floor, there are a set of storage rooms, that still have the fittings for steel strongroom doors…

The ‘Bank of Normandy’

The day after the radar station was captured it was visited by the war correspondent, Frank Gillard who was the BBC’s “man on the ground” in Normandy. Frank had set himself up in a tower at the Château de Creully 40 minutes away, from where he could broadcast to the UK. (It was a terrific location. From his tower he could look down on Monty’s HQ in the grounds of the Château de Creullet 500 metres away! He would be the first to know if anything was up!) When he got back to his studio, he reported…

“You have heard of the colossal strong-point just along the coast at Douvres where getting on for 200 Germans held out until last night. That’s a place to see. Somebody this morning called it an inverted skyscraper. That’s not an unreasonable description. Fifty feet and more into the ground it goes – four stories deep****. On the surface you barely notice it. The top’s almost flush with the ground. But going down those narrow concrete stairways you think you are going into the vaults of the Bank of England.”

Somebody, high up in the Royal Army Pay Corps (RAPC), pricked up his ears!

Between 8 June – 19 June, the RAPC had come ashore in Normandy with almost £400 million worth of currencies. The Army pays soldiers in the currency of the country they are in. Since the British Army was headed for Germany via the low countries the RAPC had to come equipped with French Francs, Belgian Francs, Dutch Guilders, Danish Florins and German Marks.

At first they had stashed it in the vaults at the Société General bank in Bayeux, but then they moved it to the cellars of the (rather gloomy and foreboding, I think) Chateau de Corseulles-sur-Mer, on Juno Beach.

All the while they were looking for somewhere a little more secure, and then they heard Frank Gillard.

By the 14th July the RAPC had taken over the Douvres radar site. On the bottom floor of the bunker they had put steel doors on five storerooms, and moved their currencies in. Each doors had a codename written on it; “Tomcat” for the French Francs store, “Fireball” for Belgian Francs, “Wilddog” for Deutschmarks, and I’m afraid I haven’t found the other two codenames.

The Bank of Normandy, as it became known, was the central hub for all British dispersements and income. All the field cash offices in the British sector came to the Douvres site for their transactions, and as the ground forces steadily built up, more and more cash was needed for circulation. So on 14 August, 445 cases of cash are shipped over from the UK. That’s £89m worth, or somewhere around £1bn in today’s money.

Eventually, as the army advanced, the bank had to move with it, and on 15 September 1944, the ‘Bank of Normandy’ closed its doors at Douvres radar station and moved to Paris, where it deposited £32.25m in the vaults of the Banque de France.

Outside the bunker on the path back to the ticket-office, there is a small plaque commemorating the work of the RAPC at Douvres.

* Douvres-la-Délivrande is both a commune and a town. During the war both were simply called Douvres. It was only in 1961 that the name was expanded to include the town’s basilica, Notre-Dame de la Délivrande, an important pilgrimage site.

*** Though not so tall. Chain Home masts were an enormous 110 metres high.

**** There are a number of these large L479a bunkers in France. One of them, Bunker L479 in Brittany, has even been transformed into a luxury holiday rental property for up to 25 people!

***** It sometimes gets referred to as “4 storeys”. It’s not. With all the concrete it might be the equivalent of a four storey building, but it only has two floors.

Declaration: I was on a self-driving research trip accredited by Normandie Tourism. Museum entry was complementary.

Factbox (2023)

Website:

Musée Radar 1944

Getting there: Franco-German Radar Museum

Route de Bény – D83

14440 Douvres-la-Délivrande

France

It’s easy to find. The Museum is well signposted from all directions and the Würzburg Reise radar stands out. There’s a car park on site.

Entry Price:

| Adult | € 6.50 |

| Reduced (disabled, students, children under 16) | € 5.00 |

| Local (residents of Couer de Nacre*) | € 3.00 |

| Children under 10 yrs | Free |

| Adult Group (10+ people. Driver & guide, free) | € 4.50 each |

| * Handy if visiting with friends from the area | |

Guides:

Audio – You can download the free audio guide in French, English, German & Dutch, by scanning the QR code at the entrance. The audio tour lasts 52 mins.

Human – Guided tours are available in English between 14 -31 July and 01 – 15 August twice daily at 12 noon and 3.00 pm. The tours are free but places are limited so it’s advisable to reserve in advance.

Opening Hours:

Open from 08 April 2023 – 12 Nov 2023 (otherwise closed)

| Apr, May, Jun, Sep, Oct, Nov |

10:00 – 18:00 Daily except Mondays |

| Jul, Aug | 10:00 – 19:00 Daily |