On 28 March 1942, the Royal Navy and British Commandos attacked the docks at Saint-Nazaire in what became known as ‘The Greatest Raid of All’. The targets of the amphibious assault, Operation Chariot, and the key locations of the onshore skirmishes are still there, and Saint-Nazaire Tourisme has created a battlefield trail for visitors interested in this historic raid.

Other Saint-Nazaire Posts

Operation Chariot – The History

It was all about protecting the vital Atlantic convoys. On 19 May 1941 the German battleship, Bismark, set off on her first and only mission, to break out into the Atlantic and attack the convoys. The rest is well-known history; eight days later she was at the bottom of the Atlantic, but not before sinking HMS Hood.

The Bismark‘s brief career traumatised Churchill and the Admiralty (and everyone else, actually!). In one short encounter she had utterly destroyed the Royal Navy’s most famous and glamorous ship, and very nearly escaped out into the vast expanse of the Atlantic. It was a close run thing, and the trouble was, she had a sister ship, the Tirpitz, who might yet succeed where Bismark had failed. No wonder Churchill told the Royal Navy that Tirpitz was their No. 1 target.

If Tirpitz were to roam free in the Atlantic she would want a base near to hand where she could repair, refit and rearm. The only port on the, now occupied, Atlantic coast of France that had a drydock big enough to take the Tirpitz, was Saint-Nazaire. If the Joubert lock was to be put out of action, it could dissuade the Tirpitz from operating in the Atlantic and relegate her to northern waters.

Bombing wouldn’t be accurate enough and the docks would be heavily defended, so the task of coming up with an alternative plan of attack was assigned to Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Chief of Combined Operations.

When is a lock (“écluse”) not a lock?

When it is a drydock (“forme-écluse” – a lock-shaped dock).

The Joubert lock – often referred to as the ‘Normandie lock’ because it is where the grand French pre-war transatlantic liner, SS Normandie, was built – is the giant sea-lock entrance to the massive Penhoët Basin at Saint-Nazaire. As with most locks, it simply allows vessels to rise up or drop down from one body of water to another using just gravity to fill or drain the water – in this case, between the basin and the sea so that ships can pass in or out.

BUT… the Joubert lock has pumps. So ALL the water in the lock can be drained, turning it into a drydock.

Wait!

If it is being used as a drydock, how do ships get in and out of the Penhoët Basin?

Easy. There are still the smaller East & South locks into the Saint-Nazaire basin, and the Saint-Nazaire basin connects to the Penhoët Basin… they go around.

Operation Chariot – The Plan

The plan Mountbatten’s team came up with, was ambitious.

The core objective, crippling the Joubert drydock, was to be achieved by ramming the seaward lock gate with a ship packed with explosives.

An obsolete WW1 4-funnel destroyer, HMS Campbeltown, was chosen for the job. She would have 4½ tons of explosive carefully hidden in her bow, she would be lightened so she could bypass the defended main shipping channel in the Loire estuary by cutting across the sand banks, and she would have two funnels removed with the remaining two, for deception purposes, cut to resemble those of a German destroyer.

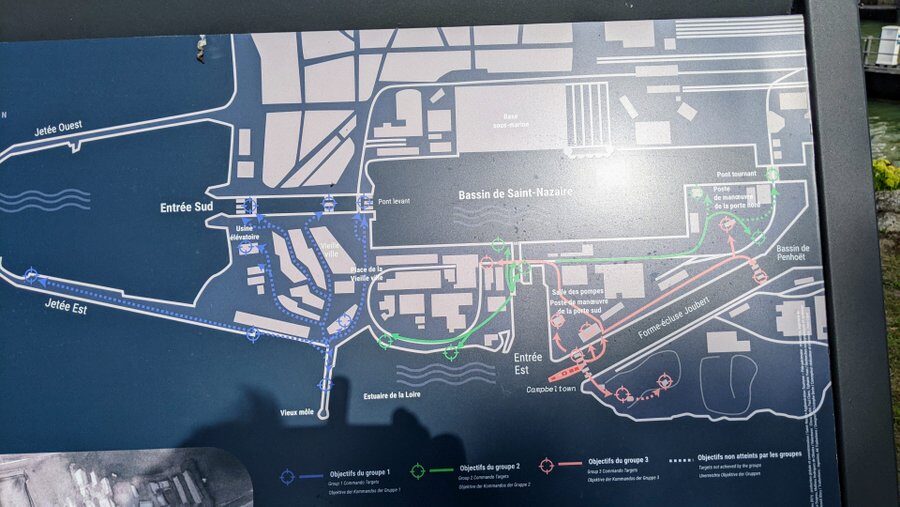

Accompanying her would be 18 patrol boats of the RN Coastal Forces comprising 1 x Motor Gun Boat (MTB), 1 x Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) and 16 x lightly armed Motor Launches (MLs). Together, with HMS Campbeltown they would carry 257 commandos whose job would be to go ashore and attack with demolition charges, twenty-four targets: 8 locks, 4 bridges, 6 technical installations, and 6 artillery positions.

Ok well, as we’re here in Saint-Nazaire…

The Joubert drydock was the priority, and among the technical installations to be destroyed were the pumping station, the lock gate controls and the inner lock gate.

But, 200 metres away on the other side of the Saint-Nazaire basin was the Kriegsmarine’s gigantic new U-boat base, just three months away from completion. Since they were there, the raid would be a golden opportunity to mess with Germany’s U-boat operations by blowing up the other sea-locks into the basin, and a few port facilities at the same time.

Once the raid was complete, the ground forces would re-embark their motor launches from the ‘Old Mole’ (where most of them had disembarked) and head out back to sea as fast as they could. Meanwhile, if successful, HMS Campbeltown‘s timed charges would set off a couple of hours later.

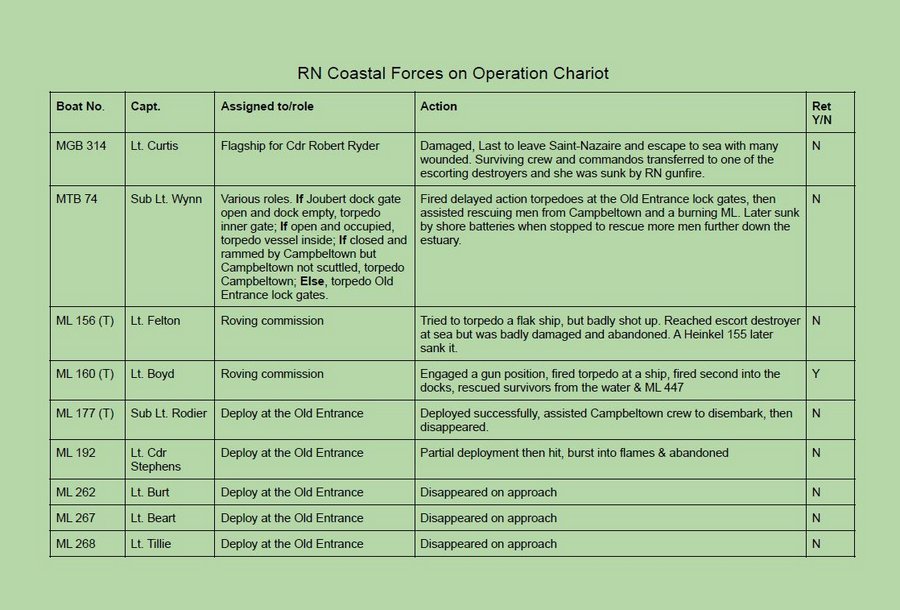

Operation Chariot – The Raid

The 19 boats (18 + HMS Campbeltown), under the overall command of Cdr Robert Ryder on board his HQ ship MGB 314, set off from Falmouth on 26 March 1942 escorted by two destroyers. The journey to the mouth of the Loire was an anxious time. The raiders did not want to be spotted en route, thus alerting the Germans. The destroyers had to sink one U-boat and take the crews off two French fishing boats before sinking them, in order to keep their presence a secret.

‘This is a queer do,’ I said to my coxswain. ‘It will soon be a bloody sight queerer, sir’ was his answer.”In the evening of 27th March, the flotilla left their destroyer escort off the mouth of the Loire and began their nervous approach up the estuary to Saint-Nazaire at 5 knots, and then 12 knots once they had cleared the sandbanks. On the way, they watched a diversionary bombing raid by the RAF on the northeast outskirts of Saint-Nazaire – the opposite direction to their approach. As it turned out, the desultory nature of the air raid raised the suspicions of the German base commander and so had the opposite effect.

Meanwhile, Lt. Boyd commanding ML 160 was noticing¹ the “sweet smell of the countryside as we steamed up the river. We could see both banks and could make out hedges and trees on the port bank.

“Before running in I was feeling frightened, but now that the show was about to start I felt absolutely calm and I had great confidence. My crew were wonderful, bandying little jokes about as we ran in. ‘This is a queer do,’ I said to my coxswain. ‘It will soon be a bloody sight queerer, sir’ was his answer.”

Three miles out, a searchlight picked them out and a challenge was flashed from the shore. They replied with a German ID code, supposedly captured from a German trawler boarded during the Vågsøy (Norway) raid in 1941, but some suggest that was a cover story for its real source, Bletchley Park. It bought them a few minutes, and then a shore battery started firing on them. They signalled that they were ‘friendly’. The firing stopped briefly and then began again more earnestly and from all sides.

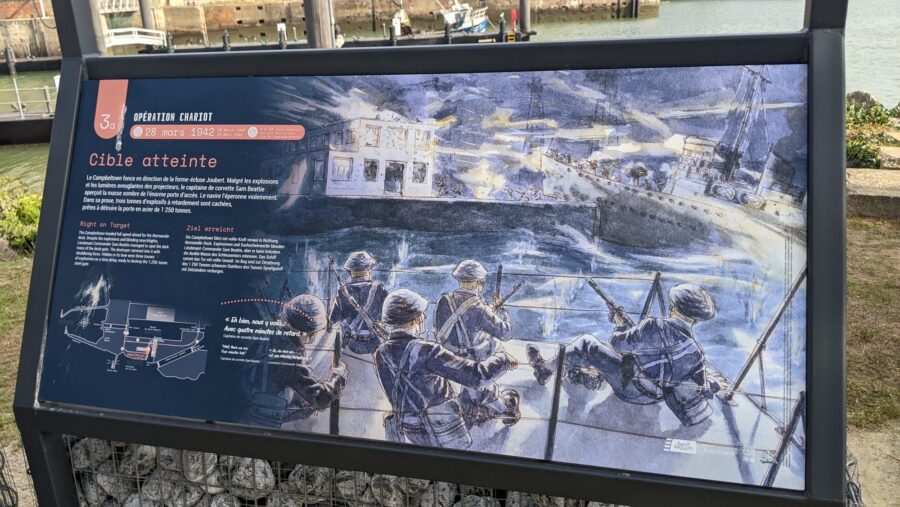

By now they were a mile from the Joubert lock. The German Kriegsmarine flag on the Campbeltown was lowered and replaced by the White Ensign. HMS Campbeltown increased her speed to 18 knots, swept past the Old Mole, through the defensive nets, and rammed straight into the lock gate… only 4 mins later than scheduled!

Now, embedded 10 metres into the gate, the crew set about scuttling her to make it difficult for the Germans to tow her clear, and her commando detachment scrambled on shore to blow up the dock gate machinery, pump house, and the underground fuel tanks on the other side of the dock.

Meanwhile the rest of the convoy was coming under intense fire and fairing rather badly.

The wooden-hulled MLs* were being shot to pieces and it didn’t help that they had petrol engines and enough fuel for the return journey. They had been split into two columns. The port column was trying to land its commando demolition teams on the Old Mole and were struggling. Many had been set on fire and some already sunk. The starboard column was heading for the steps at the entrance to the east lock – the ‘old entrance’ into the St. Nazaire basin. They too were coming under fire, not as heavy, but they were still losing boats fast.

While some commandos had managed to get ashore, it was becoming clear that the motor launches would never manage to re-embark them from the Old Mole as planned. Some launches with heavy casualties on deck, simply had to withdraw before even getting to the mole. At 02.30 Cdr. Ryder decided to retreat. Of 17 boats that had entered the estuary only 8, possibly 9, managed to withdraw from Saint-Nazaire and limp back towards the open sea. The rest were either in flames, sinking, or sunk, leaving valiant commandos and seamen ashore, many wounded, but a few still fighting in fierce close quarters firefights around the dock area.

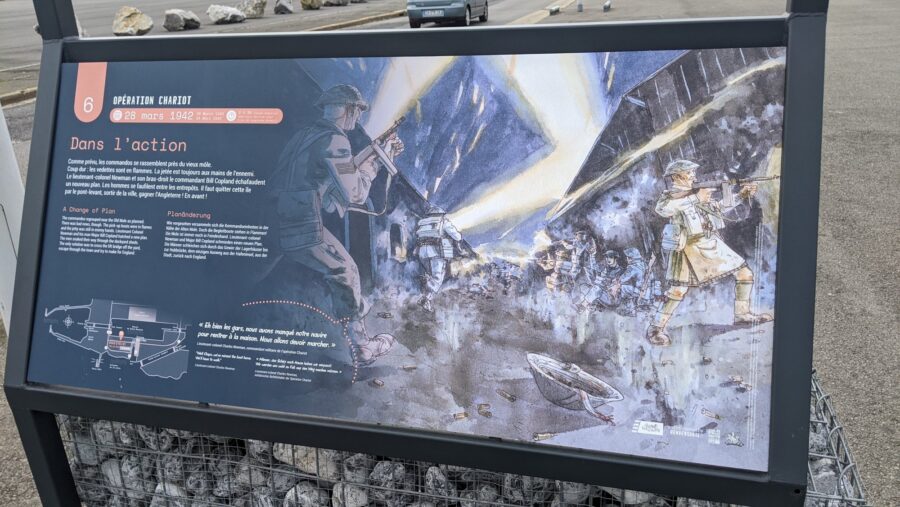

At around the same time (02.30am) the senior officer of the Commandos, Lt Col. Charles Newman, in the thick of the fighting in the dock area only a couple of hundred metres away, came to the same conclusion. He realised they were not going to get away from the Old Mole and ordered his men to make a break for the bascule bridge over the south lock and try to escape through the town and make their own way back to England. This was their last stand. Most were killed or captured.

Operation Chariot – Aftermath

On the face of it, the raid may have seemed like a shambles. Especially since the explosives on HMS Campbeltown failed to detonate on time (04.30 am), leaving the captured men wondering if they had failed in their main objective. However, the charges went off at noon, smashing the lock gate and blowing what was left of it off its sill. The explosion killed around 360 German soldiers, officers, and dockyard workers.

Then, two days later, on 30 March at 4.30pm the delayed action torpedoes fired from MTB 74 at the Old Entrance East Lock gates erupted causing total panic in which a number of Todt Organisation workers were misidentified as more British Commandos and shot.

A few months after the raid, an RAF photo reconnaissance image shows the huge temporary sand banks the Germans built at each end of the Joubert dock so they could start repair work, but it remained out of commission for the rest of the war. It stayed non-operational till 1948.

The aerial photo also shows the remains of HMS Campbeltown in the dock, and there is a better close up of the wreckage on the Saint-Nazaire EcoMusee (heritage museum) site.

In total 612*** men took part in the raid. 346 were Royal Navy sailors. 265 were Commandos from the British Army’s No.2 Commando. Of these men, 169 were killed on the raid and 215 were taken as prisoners of war (106 RN and 109 commandos). Only 228 men made it back to England.

There are details of the men who took part on the Saint-Nazaire Society website. The Saint-Nazaire Society oversees the memorial events, keeps alive the memory of the raiders, and had a hand in creating the Operation Chariot Trail.

Operation Chariot – The Trail

On 28 March 2017 a ceremony took place to mark the 75th anniversary of the raid.

In preparation for the anniversary, Saint-Nazaire moved the Operation Chariot commemorative stela (pillar) that had been in the Place du Commando near the outer harbour, to its new home by the Old Mole (Vieux Môle) for the ceremony.**

At the same time they commissioned a French illustrator, Benoit Blary, to design a set of seven numbered infographic panels to be erected at some of the key locations of the raid so that visitors could self-guide themselves around the battlefield.

The 2 km circular route starts and finishes just by the bascule road bridge over the south lock. (Helpful hint: We searched all over for sign No.1 and gave up looking. We eventually found it when we completed the trail… on the reverse side of No.7! Duh!)

No.2 is located near the Operation Chariot commemorative stela by the Old Mole. The mole looks so ordinary and peaceful now. It’s really hard to picture it as the focal point of so much violence and destruction on that night, 80 years ago.

No.3 is actually two signs, 3a & 3b. They are located at the Old Entrance right opposite the Joubert Lock gate which HMS Campbeltown rammed – a busy spot!

No.4 is on the roof of the fortified lock (where the Submarine Espadon and the EOL – Centre éolien are now housed). The fortified lock didn’t exist when the raid took place in 1942, but thanks to the raid, the Germans decided they needed to beef up their defences. They started building the new lock and concrete covering, next to the East Lock (Old Entrance) at the beginning of 1943.

There is a steel staircase up the side of the fortified lock (or a lift if you prefer) that takes you to the roof where you have a panoramic view over the whole battlefield. Here you’ll find infographic No.4 and HMS Campbeltown‘s QF 12-pounder 3-inch (76.2 mm) forward gun, which Saint-Nazaire placed here during the preparations for the 75th anniversary.

The infographic is especially informative. The illustration matches the view beyond it. It shows the small dock to the side of the East Lock, which is where the Germans dug out the new fortified lock on which this sign now sits. And it shows the busy dockside buildings and warehouses opposite where much of the street fighting took place. Now, apart from couple of buildings such as the Écomusée and the EDF wind farm office, it is a wide open space.

Also worth noting, on the corner of the fortified lock roof is a concrete machine gun emplacement with a Maginot Line style metal cupola. It looks straight down on the Joubert Dock gate – they weren’t going to make it easy for anyone trying that raid again!

No.5 is at the far end of the Joubert Lock by the Penhoët Basin. This marks the furthest point of the raid, where the commandos from the HMS Campbeltown group came to blow up the mechanism for the inner gate.

No.6 on the return journey, is on the side of the Saint-Nazaire basin (the submarine basin) where some of the fiercest close-quarter fighting took place among the dock buildings and warehouses that were there at the time. It’s an empty space now; car parks mostly.

No.7 is back by the bascule bridge.

You can get the trail map, an A5 leaflet, free from the Tourist Office in the submarine base, or you can download it as a PDF.

The Joubert Lock is these days being used as the centre of operations for the offshore wind farm industry. Two years ago, while preparing the lock for its new role, they discovered a mangled piece of metal on the seabed outside. It is thought to be a piece of HMS Campbeltown, and it is due to be put on display in a museum in the UK – find out more.

¹ ‘The Battle of the Narrow Seas’ by Lt. CDR. Peter Scott, 1st edition 1945, Chapter 5.

July 1981

(Photo: Tim Webb CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

* Anyone remember the blue-painted ‘Western Lady’ ferries in Torbay (Devon) in the 1980s? They were ex-RN Motor Launches built during the war. I wouldn’t like anyone shooting at me in one of those!

** At the same time they also moved a plaque dedicated to the 4,000 British soldiers who died in the sinking of the Lancastria in 1940 (that’s another story) and reinstalled it in Place du Commando in time for another anniversary remembrance ceremony on 17 June 2017.

*** There were also, according to one report, two journalists on the raid. I can only find reference to one of them; Mr Gordon Holman (author of ‘The Little Ships’) who was onboard Cdr Ryder’s flagship MGB 314, and who was later mentioned in dispatches for his help attending to the wounded.

Declaration: I was on a self-driving press trip as a guest of the Saint-Nazaire tourist office.