The Écomusée in the old port area of Saint-Nazaire focuses on the port’s historic, industrial and maritime heritage.

Who knew!?

Most Anglophones, me included, think the “Éco Museum” is something to do with the environment, and probably linked to the EOL-Wind Turbine experience nearby. I wouldn’t have gone there if we hadn’t been walking literally past the door and stuck our heads in. I’m glad we did.

It’s not a large museum – it occupies a single large industrial unit – but it tells, through mostly models and photographs, the story of Saint-Nazaire’s growth from the Stone Age to the present.

Other Saint-Nazaire Posts

The trail through the museum starts with a small model display of Saint-Nazaire’s oldest edifice, the Tumulus of Dissignac in the west of the commune. It is a megalithic monument dating from around 5,500 BC, which makes it not only the oldest monument in the Loire-Atlantique department, it is also 2,000 years older than the oldest pyramid in Egypt!

The Tumulus of Dissignac site is run by the Écomusée and you can buy tickets to go and visit it.

Shipbuilding comes to Saint-Nazaire

In 1850, Saint-Nazaire at the mouth of the Loire estuary was just a harbour – the “avant port” to the city of Nantes further up the river. Its main business was providing pilots for ships going up river. Then it began to grow. In just thirty years it was transformed from a village with a population of 800 to a city of 15,000.

It was triggered by the dynamic growth of the economy in the ‘Second Empire’ (1852–70) under Emperor Napoleon III, which saw the construction of the first basin with a lock in 1856, and a year later, the arrival of the railway. In 1860 two bankers, the Pereire brothers signed a 20-year contract with the French government to provide postal services between Le Havre & New York and Saint-Nazaire to the Caribbean and South America. As part of the deal they agreed that half their fleet would be built in Saint-Nazaire.

The director of shipbuilding at the Ministry of the Navy knew just the man for the job: a young marine engineer from Glasgow, John Scott. In 1862 the construction of the Chantier Scott shipyard gets underway, and a second huge dock basin was dug at Penhoët in 1881. Naturally workers and merchants poured in, and developers grabbed as much land around the port and along the seafront as they could to build housing, warehouses and workshops.

John Scott was quick off the mark. He built the first new “paquebot” (mailship) for the Pereire brothers’ CGT (Compagnie Générale Transatlantique) Central American Line in 1864.

Empress Eugenie was a mixed propulsion ship – paddlewheels and sails. She set off on her maiden voyage to the Antilles and Veracruz on 16 February 1865. Later, she was converted to a propeller ship. She ended her career in 1873 as the first of 621 ships to be built in Saint-Nazaire over 150 years, including the famous transatlantic liners Normandy, France and later, Queen Mary 2.

There are large models of the Normandy and France in the museum, and one of the French Navy’s most formidable warships when she was finally commissioned in 1955, the battleship Jean Bart *.

By the time a fifth ship, the Saint-Laurent, was delivered to CGT in 1866, a small recession had set in. The marine & banking industries were struggling financially, and Chantier Scott was declared bankrupt on 25th November 1866. It was taken over briefly by its customer CGT, but eventually closed its doors in 1870.

Eleven years later, part of the site was reborn as Chantiers de la Loire, and a year later in 1882 a second shipyard, Chantiers de Penhoët appeared. These two shipyards on the Penhoët peninsula between the emerging giant Penhoët basin and the shore of the Loire, became generally known as the ‘Loire & Penhoët shipyards’… until their merger in 1955 when they became Chantiers de l’Atlantique.

The museum has two large dioramas depicting the layout of those shipyards in the late 19th century and today. The contemporary diorama is not an accurate or detailed model of the Chantiers de l’Atlantique, but a diagrammatic representation to explain (especially for schools groups) how the shipbuilding process works and how the ships pass through the production sequence.

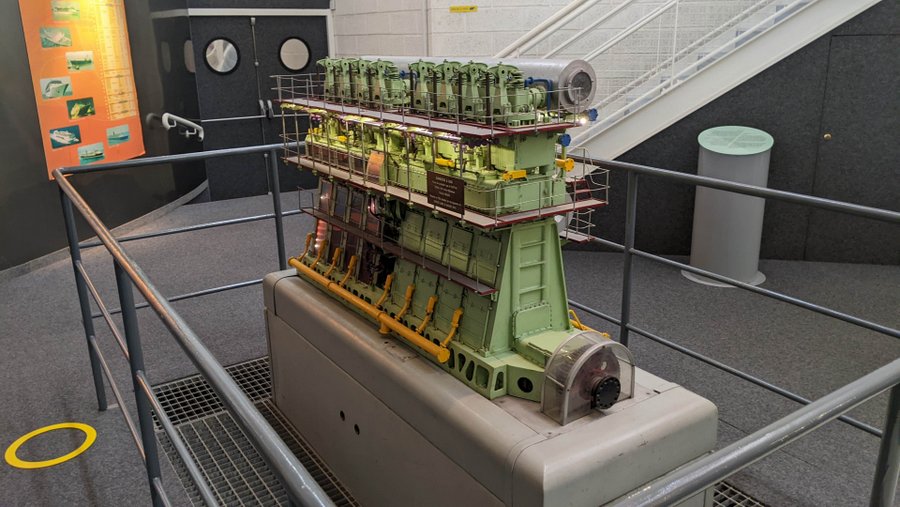

One artefact that stands out is a 1:10 scale model of a 7,000 horsepower Burmeister & Wain marine engine.

It was made by the apprentices of the Loire & Penhoët shipyards in 1950.

Aviation comes to Saint-Nazaire

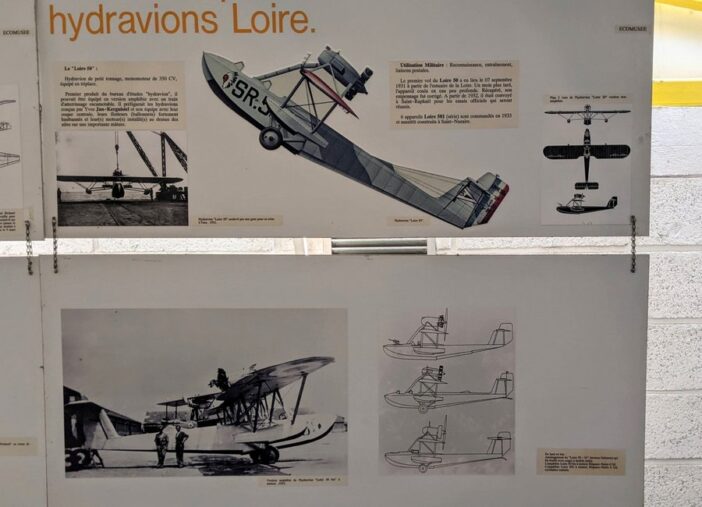

The balcony level of the Écomusée is especially interesting. The walls are covered with photo displays highlighting some of the aircraft and their creators who gave birth to the aviation industry in Saint-Nazaire, resulting in today’s giant Airbus facility, just up river from the Chantiers de l’Atlantique shipyard.

Around the 1920s, the Loire & Penhoet shipyards started to build seaplanes using techniques acquired from the navy. It was a natural extension for them. The post-WW1 global economy was struggling to recover and with fewer naval ships required, shipyards were also struggling. Chantiers de Penhoët, for example, was forced to reduce its workforce from 3500 to 1700 and look for ways to diversify.

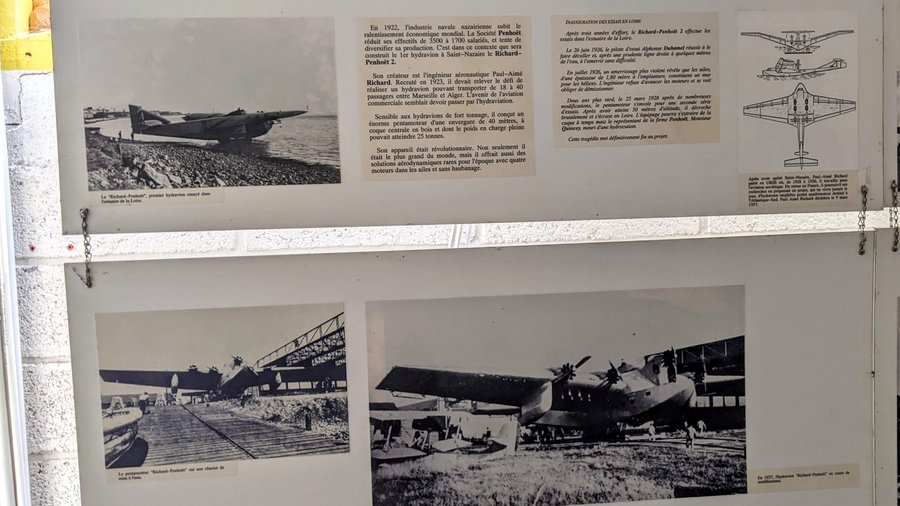

Young aviation designers and engineers, like Paul-Aimé Richard, excited by the new aeronautical technology that had leapt forward during the war, were eager to create new aircraft and new ideas. Richard was hired by Chantiers de Penhoët in 1923 to design hydro-avions (seaplanes) starting with an aircraft that could transport 18 – 40 passengers between Marseille & Algiers.

He came up with the Richard-Penhoët 2, which was revolutionary. With a wingspan of 40 metres it was the largest seaplane at the time, but its unique design element was having four of its five engines embedded in the un-stayed wings. Unfortunately, while unique and revolutionary, it under-performed and after ten test flights, fatally crashed in the Loire in 1928. The project was cancelled and Richard went to the newly formed USSR to design aircraft for the Russian air force.

An inauspicious start to the aviation industry in Saint-Nazaire perhaps, but it didn’t stop the young designers from creating some amazing prototype seaplanes.

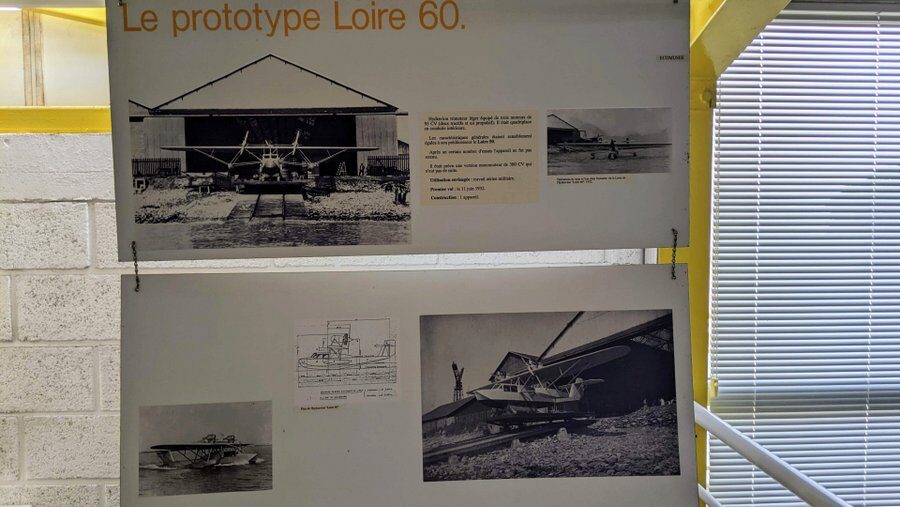

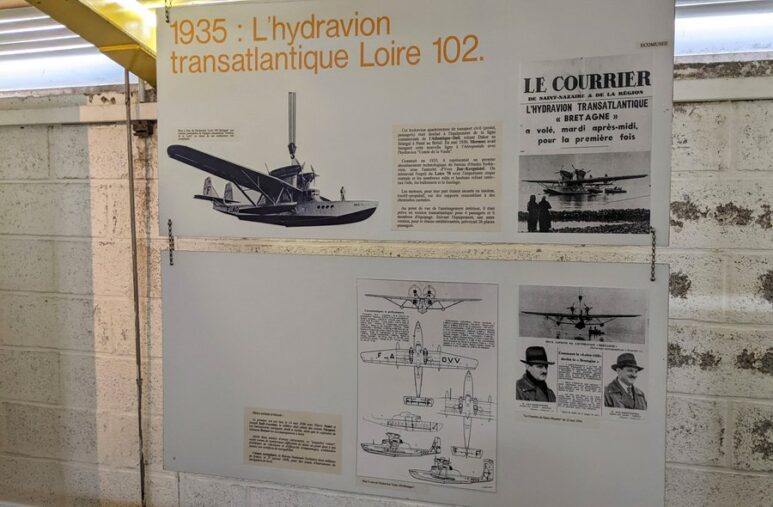

The Loire 50 was single-engined flying boat prototype made by Loire Aviation, a subsidiary of the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire (ACL) shipyard**. Its first flight was on 7 Sep 1930. It went into limited production (12 aircraft) as the Loire 501, and they were still flying up to 1940. Its trimotor variant, the Loire 60, never went into production. Nor did the Loire 102 (they must have skipped over a few models!), which first flew in May 1936. But it did look impressive. It was designed to be a mailplane on the South Atlantic route between West Africa and Brazil.

The oddest looking prototype was the Loire-Nieuport 10. It was intended to be a long-range maritime reconnaissance/bomber, and was a joint venture between Loire Aviation and Nieuport-Delage. It had a crew of six, could carry bombs or 2 x torpedoes in an internal bomb bay, and a whacking great 20mm cannon in the rear-facing dorsal turret! Like the Japanese ‘Betty’, you’d be wary attacking that from behind!

It first flew on 21 July 1939, just before WW2 started. However the programme was cancelled because the French Navy decided it was going to switch to using land-based aircraft. A shame, I’d like to have seen some of those in action with the Free French forces. It reminds me of the Heinkel 115.

The aircraft industry in Saint-Nazaire also came ashore after WW2. France’s twin-engine Cold War jet, the Vautour, first flew in 1952 and then four years later went into production in Saint-Nazaire. The factory produced 30 x single-seat ground attack variants, 40 x 2-seater bomber variants, and 70 x 2-seater night fighter variants. And when Concorde went into production after its first flight in 1969, the Saint-Nazaire factory was allocated ‘Section 20’ – the fuselage & tail section of the wing with engine mounts.

It’s fascinating to see in the Écomusée displays, how Saint-Nazaire’s industries have grown and adapted… and continue to adapt with the recent move into the wind power industry.

And it’s also funny to think that for almost a century, its shipping, ship-building, and seaplane industries were inextricably linked to the mail service… while a nascent competitor, the telecommunications industry, was literally undermining them. In 1862, as the shipyards were being established, the first transatlantic telegraph lines were laid from South America to France. They came ashore at Saint-Nazaire!

* Chantiers de l’Atlantique will be building another capital ship for the French Navy soon – the PANG (Porte-Avions de Nouvelle Génération) new generation nuclear-powered aircraft carrier that’s due to replace their current aircraft carrier, Charles de Gaulle, in 2038.

** Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire (ACL) was formed in 1881 in Nantes and specialised in warships. They built a second yard in Saint-Nazaire in 1882 next to the Chantiers de Penhoët yard.

Declaration: I was on a self-driving press trip as a guest of the Saint-Nazaire tourist office. Museum entry was free.

Factbox

Website:

Saint-Nazaire Tourisme – Écomusée

(Saint-Nazaire Tourisme operates all the key sites and tours in the Saint-Nazaire commune, so their website covers each site and handles ticketing.)

Getting there:

Écomusée

Avenue de Saint-Hubert

Saint-Nazaire

France

The Écomusée heritage museum is on the opposite side of the submarine base basin, near to the fortified lock where the Submarine Espadon is located – a 10 minute walk from the submarine base.

Entry Price (2023):

| Adult | Reduced* | Child (4-17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EcoMusee | € 5.00 | € 4.00 | € 2.50 |

| Transat Pass (Écomusée + Escal’Atlantic) | € 16.00 | € 8.00 | |

| Heritage Pass (Écomusée + 1 guided tour of submarine base OR Dissignac Tumulus) | € 10.00 | € 5.00 | |

| Combined Ticket (Escal’Atlantic + Espadon submarine + Écomusée + EOL Centre Éolien) | € 28.00 | € 14.00 |

* Reduced tickets are for students, job seekers, people with disabilities with one accompanying person

Children under the age of 4 and Annual PASS holders have free entry. Admission is also free on the first Sunday of the month, except July and August.

Opening Days:

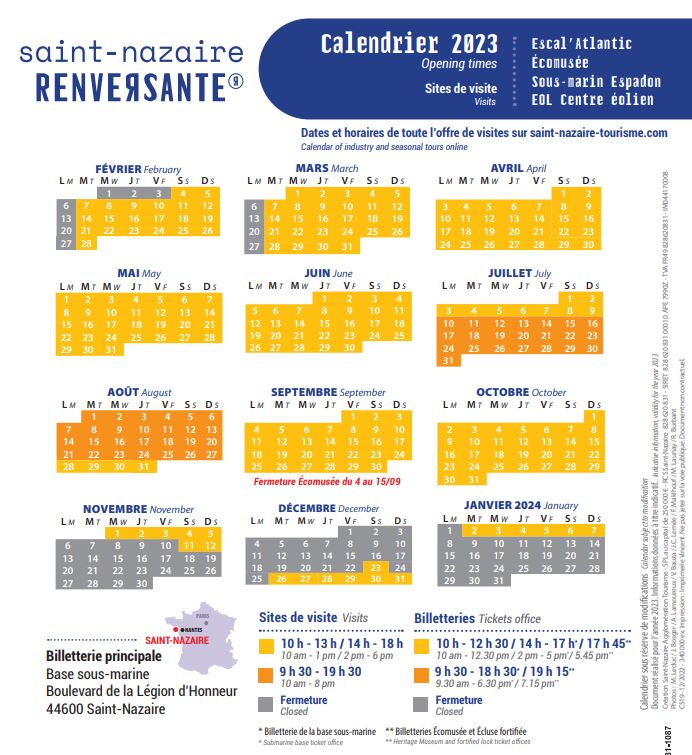

The four Saint-Nazaire Tourisme attractions (EOL Centre éolien, Submarine Espadon, Écomusée & Escal’Atlantic) share the same calendar. They are open on most days during the summer but as you get into the winter the dates become more specific and you need to check if the actual date you want to visit is available on the website.

The four Saint-Nazaire Tourisme attractions (EOL Centre éolien, Submarine Espadon, Écomusée & Escal’Atlantic) share the same calendar. They are open on most days during the summer but as you get into the winter the dates become more specific and you need to check if the actual date you want to visit is available on the website.

Opening Hours:

Tickets for the four attractions are timed. Tickets for the Écomusée are based on a 45-minute visit (too short, I could have spent an hour there) and sold in 10 minute time slots.