The twin-engine Bristol Blenheim was the RAF’s primary light bomber at the start of WW2.

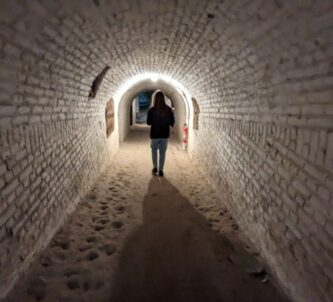

This one, a Blenheim IV, is on display at the RAF museum in Hendon. (When we can get to see it!)

The Bristol Blenheim – or ‘Bolingbroke’ if you were flying the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) version made under license in Canada – was a versatile aircraft, used as a bomber, night fighter, & for reconnaissance, and in many theatres/campaigns such as Norway, the Low Countries, the Mediterranean, North Africa, the Middle East and the Far East.

I often think it was under-recognised. The glamorous Mosquito grabbed the attention, while the Blenheim was the workhorse!

There are some good books to read about their exploits, Such as Stuart R. Scott’s 1996 book Battleaxe Blenheims – 105 squadron RAF at war 1940-1 (See below). It has some interesting observations and poignant tales of their time in Malta.

There’s also a book by Ron Gillman, The Shiphunters, about 107 Squadron.

But it was the book I am reading at the moment, Martin Bowman’s The Reich Intruders: RAF Light Bomber Raids in World War II, that triggered this post

This one is at the National Museum of Flight, Scotland.

In the chapter covering the immediate pre-war period in April 1939, Wing Commander Basil E. Embry took over command of 107 Squadron at Wattisham and set about a rigorous training programme to get his pilots and ground crew ready for the war that he was sure would break out at any moment.

There is a description from Aircraftsman First Class (AC1) D. M. Merrett who is an armourer with the squadron, about the relentless workload and about changes they made to improve the aircraft’s defences.

The Blenheim had a semi-retractable turret on top and a machine gun position in the nose, but it was vulnerable to attack from behind and below. This worried Embry and his pilots, so they set about improving it. They found space at the back of the engine (& undercarriage) nacelles and fitted two .303 Browning machine guns in them, projecting out of a hole and pointing rearward. They were operated by Bowden cables fed up to a large lever in the cockpit.

In addition they fitted a Vickers Gas Operated (VGO) gun in the stern frame behind the tail wheel also operated by a lever connected by Bowden cable – a ‘sting in the tail’ as you might say!

But the bit I didn’t know and found fascinating, was his description of the bomb payload and how it worked.

“The bomb doors were not hydraulically operated. They merely flew open when the weight of a bomb fell on them and were returned to the closed position by bungy cords.”

Wait! What?!

I’ve since seen it suggested that this system may account for the Blenheim’s poor targeting; the time each bomb might take to squeeze through the doors could vary and those tiny changes resulted in a wide dispersal on the ground.

Who knew?! (Well, I didn’t!)