There is a completely ordinary lump of concrete on the grass near the entrance road at the National Museum of Flight, with a rusty metal ring on it. Most visitors – probably all visitors (certainly me!) – wouldn’t even notice it as they drive in.

But it is a clue to the origins of this former airbase, and it pre-dates the WW2 era buildings.

East Fortune Airfield in East Lothian, 20 miles from Edinburgh, started life in 1915 as a naval aviation base for airships, including the famous R34 – the first airship to cross the Atlantic (from East Fortune). The block of concrete is a mooring block used to anchor airships to the ground.

The airfield remained operational for 2 years after WW1 and was then closed and scheduled for disposal, but along came WW2. RAF East Fortune was reconstructed and operated as a training station. After WW2 it was again slated for closure, but along came the Cold War, and its runways were extended for long-range strategic bombers. They were never used. Once again the airfield was closed, but along came civil aviation(!) and for a brief period in 1961 East Fortune became an airport before finally the main runway was closed for good (part of it is used for microlights and as a race track).

Meanwhile, in 1971 the Royal Scottish Museum (Edinburgh) was given a Spitfire XVI which they couldn’t display in Edinburgh so it was stored at East Fortune and triggered the birth of the National Museum of Flight in 1976.

So what’s there now?

Well, the whole site is preserved as a WW2 RAF airbase with many of the original buildings and shelters. The collection of just under 50 aircraft are nearly all housed in three large hangars: Civil Aviation, Military Aviation, and the largest hangar, The Concorde Experience and The Jet Age.

The Concorde Experience and The Jet Age

If you want to see Concorde, this is a good place to do it. There are seven* Concordes on static display in the UK, and this one (G-BOAA), in its purpose-built hall, is one of the best to see. You can get on board and underneath (no barriers to keep you away), and it is one of the operational Concordes (the first, actually, operational from 1976) from the British Airways fleet, in excellent condition – as opposed to the prototypes (Duxford & Yeovilton). It looks as if you could wheel it outside & take-off.

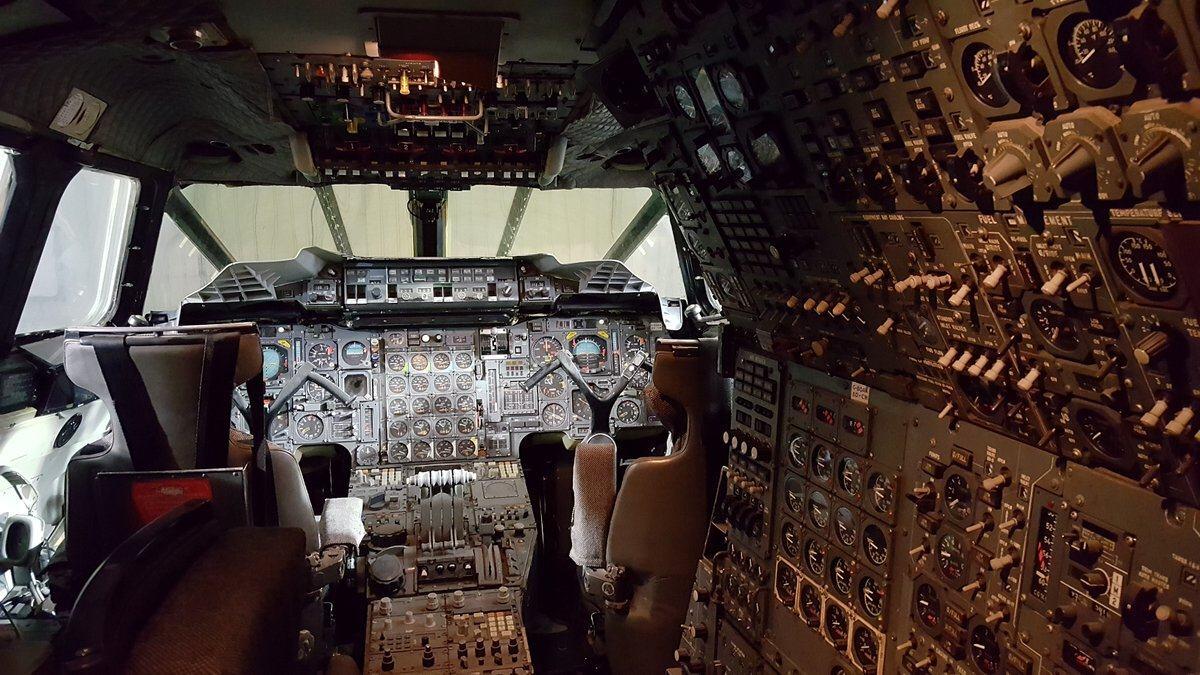

The one place you can’t get in to is the tiny cockpit bristling with switches and instrumentation. It looks amazing and definitely worthy of a photo, so, listen up aviation museums worldwide… and learn! The National Museum of Flight has done something truly simple and brilliant – cut a hole in the perspex wall so you can take an in-focus photo without light reflections all over it! I’m sure they are not the first, but they are the first I’ve seen, and it’s a lesson all museums – not just aviation museums – could make use of.

There are some good displays around the hangar of Concorde memorabilia, telling the story of Concorde, and the hangar also houses some examples of classic jet engines, plus the front section of a Boeing 707 fuselage – the aircraft that (along with the Comet 4 – there’s one of them outside) heralded the age of jet travel.

Military Aviation Hangar

The collection here is a mixed bag of familiar aircraft. Almost everybody has an ME 163 Komet, a Spitfire (albeit a slightly rarer Mk 16 version), a Harrier and a Meteor (Gloster or Armstrong Whitworth variant), and The English Electric Lightning, Sepcat Jaguar, and Panavia Tornado are not the rarest of air museum artifacts.

But it’s a nice collection and there are some small jewels in here.

Given the numbers produced, Bristol Blenheims are rare-ish (there’s one down at Duxford) and here at East Fortune they have a Bristol Bolingbroke which was the name given to the Blenheim built under licence in Canada. They are more plentiful in museums on the other side of the Atlantic!

The Hawker Sea Hawk, a Fleet Air Arm fighter from the 1950s when the UK still had proper aircraft carriers (don’t start me on what we have now!), is not rare – there’s one at Duxford, two at Yeovilton, one at Newark, etc – but it’s a really elegant jet fighter that meets my single role, fit-for-purpose design criteria, and I’m always happy to see one.

On the other hand, the De Havilland Sea Venom, is quite rare. There are barely half a dozen scattered around the world, so it’s a shame this one isn’t showcased in more space. It’s not as pretty as the Sea Hawk but it’s a worthy machine, highlighting the period in the post-war years when we were flirting with twin-boom aircraft (The Americans seemed to have grown out of it earlier eg. P38, P61).

Mig 15s are not rare, but the one at East Fortune is slightly unusual in that (rather like the Bolingbroke Blenheim) its a Czech Aero S-103 made under license in the 1950s.

There was one little gem I found in the display cases – a WW2 “escape boot”. A traditional fur-lined flying boot designed so the top could be cut off leaving a downed airman in enemy territory wearing a much less conspicuous pair of brown shoes!

Civil Aviation Hangar

I’ll be honest. I’m not as excited by small civilian aircraft, however historically significant they are, as I am by military aircraft. So I found this hangar… interesting – worthy but a little dull!

The 1950s De Havilland Dove is a pretty aircraft, the 1930s De Havilland Rapide is a ‘classic’, the 1960s Scottish Aviation Twin Pioneer is a bruiser, and the 1970s Britten-Norman Islander is an amazing workhorse… but I just can’t get remotely excited about the 1950s Beech E18S or the General Aviation Cygnet or Miles M18 from the 1930s. Gliders & microlights leave me cold too (They have a couple. Remember, part of the remaining runway is still used for microlights).

On the other hand, this hangar has a couple of autogyros, which are really interesting to see up close. I’m not sure you’d ever get me up in an autogyro but the principle of their unpowered rotor-borne flight is fascinating!

The rest of the airfield

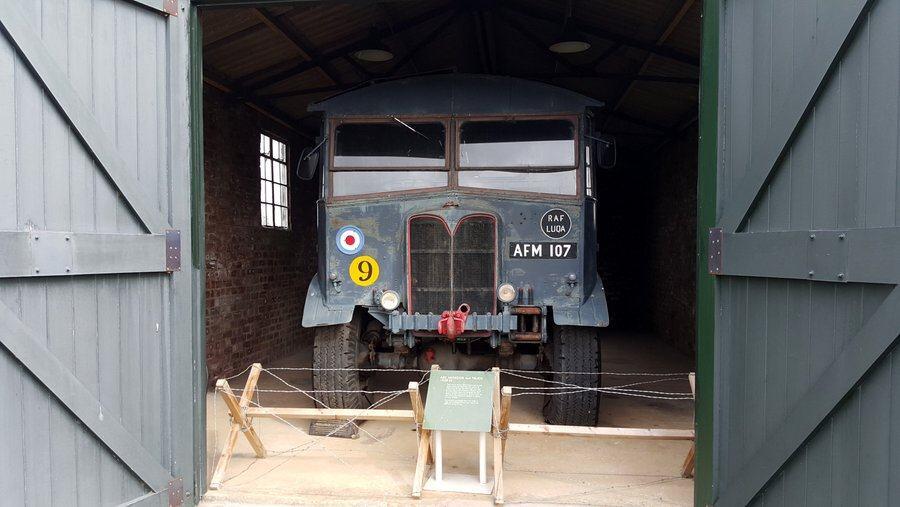

There are a couple of larger aircraft on display outside – a Vulcan, a Buccaneer (one of my favs. I’m sponsoring one at the Yorkshire Air Museum) and a Dan Air Comet 4 that you can explore inside. There are also some incidental exhibits outside or in their own open building, like a 1950s Bedford Green Goddess fire engine; a WW2 RAF Matador 10-ton 4wd truck that was based at Luqa airfield on Malta (I wonder if it carried crew or gear for 105 Sdn or Z Flight?); and a 1950s surface to air missile (SAM) which I confidently declared to be a Bristol Bloodhound (Good old Airfix!) and which actually turned out, when I got up close, to be the nearly identical but smaller English Electric Thunderbird Mk1 used by the British Army. Can’t be right all the time! 😉

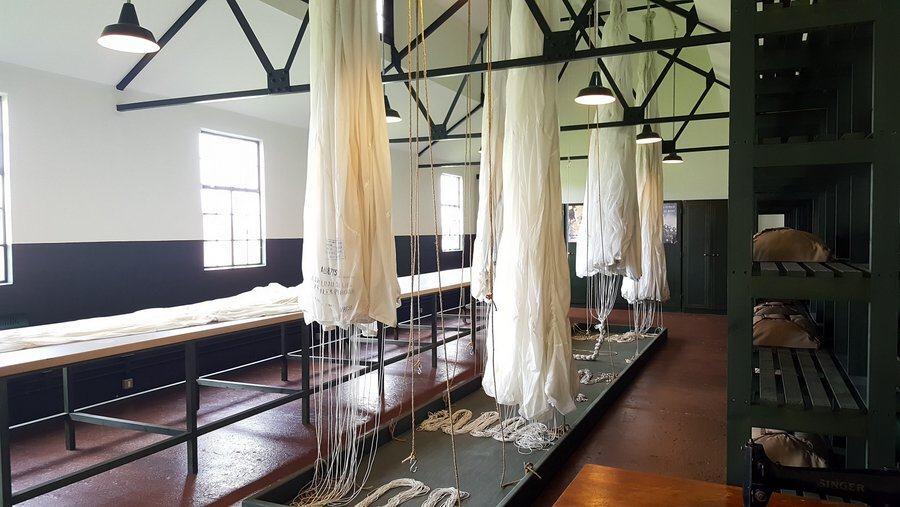

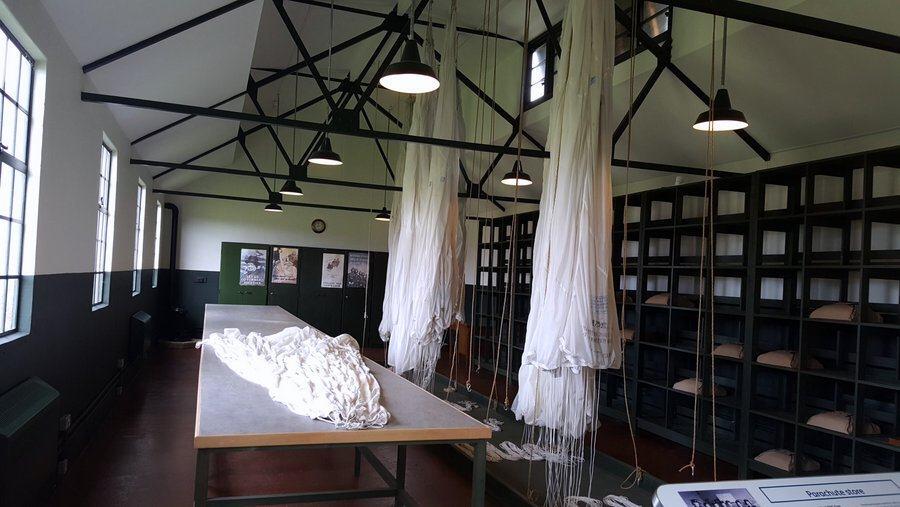

Some of the smaller buildings & Nissen huts on the site have been renovated to house specific exhibitions & displays. There’s a family friendly interactive displays building – Fantastic Flight – and the Fortunes of War exhibition covering the history of the airfield, and my favourite the Parachute Store restored to its WW2 condition.

The Parachute Store was where parachutes were dried and re-packed.

… What? After being used in the rain?

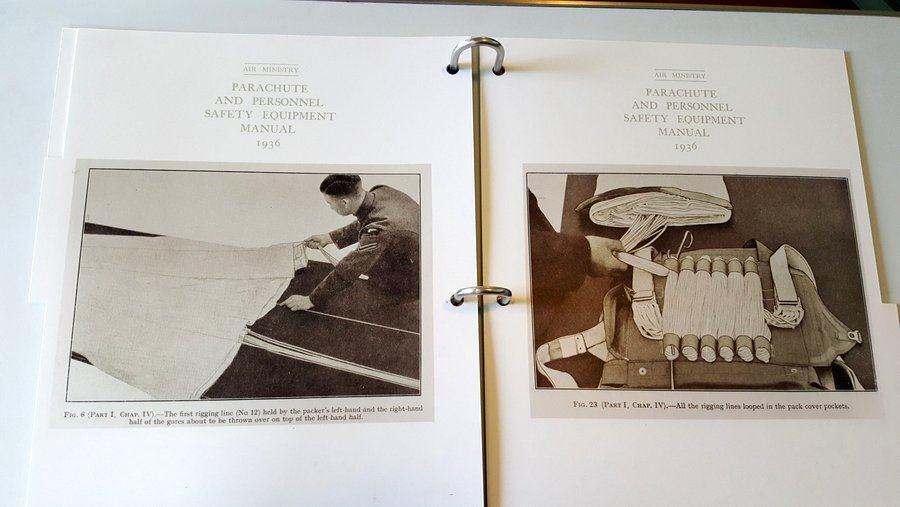

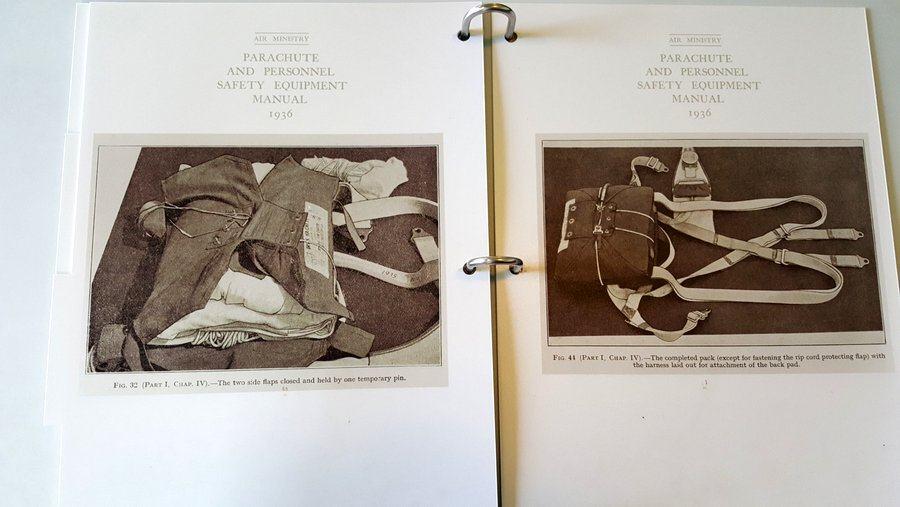

No. I didn’t know this, but “Many aircrew sat on their parachutes in what were termed ‘seat packs’, while other types were worn on the back or chest depending on the type of aircraft they flew in. After a period of being carried in aircraft the parachutes would become compressed in the pack and absorb moisture. So they needed to be dried and re-packed regularly,” according to the signage. I learnt a bunch of stuff about parachutes that I didn’t know from the displayed Air Ministry Parachute Packing Manuals, and the introductory paragraph is a masterclass in under-statement!

“To be of full value to its user, a parachute must inspire absolute and implicit confidence in its correct functioning.”

* There’s a handy list of the 18 surviving Concordes and their locations, here.

Declaration: No need really. I was driving in Scotland, made my own visit and paid my own entrance fee. As usual, I’ll say what I think anyway!

Factbox

Website:

www.nms.ac.uk/national-museum-of-flight

Events:

They have an annual airshow in the summer, but without a runway all the visiting aircraft are in the air, and that can be subject to weather conditions. Much of the 2017 programme was cancelled due to bad weather.

Getting there:

National Museum of Flight, East Fortune Airfield, East Lothian, EH39 5LF.

Easiest to drive. It’s about 20 miles east of Edinburgh and only a mile or so off the A1. Parking is free.

Getting about:

Like all airfields (and airports) buildings are spread out, so distances are shortened by their ‘Airfield Explorer’ – a free continuous shuttle train thingy on a circuit around the airfield. If you are not in a hurry and/or don’t have tired kids with you, it’s perfectly walkable.

Price:

Adult £12

Concession £10

Child: £7 (under 5 free)

Family: £31 (2 adults and 2 children)

NMS members: Free

Opening Hours:

Summer (Apr-Oct): 10am – 5pm, every day

Winter (Nov-Mar): 10am – 4pm, Sat & Sun only

Last admission is an hour before closing time.