Parham Airfield Museum is actually two museums rolled into one. For the most part it is a memorial museum for the USAAF 390th Bomb Group who were based here during WW2, but it also houses the Museum of the British Resistance Organisation – one of Britain’s best kept wartime secrets… the BRO that is, not the museum!

Parham, aka Framlingham, airfield.

Built up on the hills near the village of Parham in 1942 as a Class A (Heavy Bomber) airbase for the USAAF, the base was officially known as ‘AAF Station 153 – Framlingham’ *. The historic town of Framlingham is 4 miles away.

Its first occupant was the 95th Bomb Group, who after a bad mauling were withdrawn to Station 119 at Horham, 10 miles away, to lick their wounds and reorganise. A month later in July 1943, the 390th Bomb Group settled into their new home.

The four 390th Bomb Group squadrons – the 568th, 569th, 570th, and 571st – flew B-17 Flying Fortresses. From their first combat operation (to Bonn) in August 43, to their last in April 1945, they completed 300 missions for the loss of 144 aircraft. 740 servicemen were killed or ‘Missing in Action’ and 754 were taken as Prisoners of War. Their most famous survivor was a gunner, Master Sergeant Hewitt Dunn, who completed 104 missions (including nine to Berlin) – a record in the Eighth Air Force.

USAAF 8th Air Force Memorial Museums

| 100th Bomb Group Museum – Thorpe Abbotts | 95th Bomb Group Museum & Red Feather Club – Horham |

| 390th Bomb Group Museum – Parham Airfield | 446th Bomb Group Museum – Flixton (at NSAM) |

390th Bomb Group Memorial Museum

The museum is squeezed into a number of Nissen/Quonset huts and the control tower itself. Most of its collection is made up of personal memorabilia, historic photographs, aviation equipment and ‘wreckology’ – parts of aircraft recovered from crash sites.

In one Nissen hut they have recreated a typical aircrew barrack, with beds, belongings, showers & washroom.

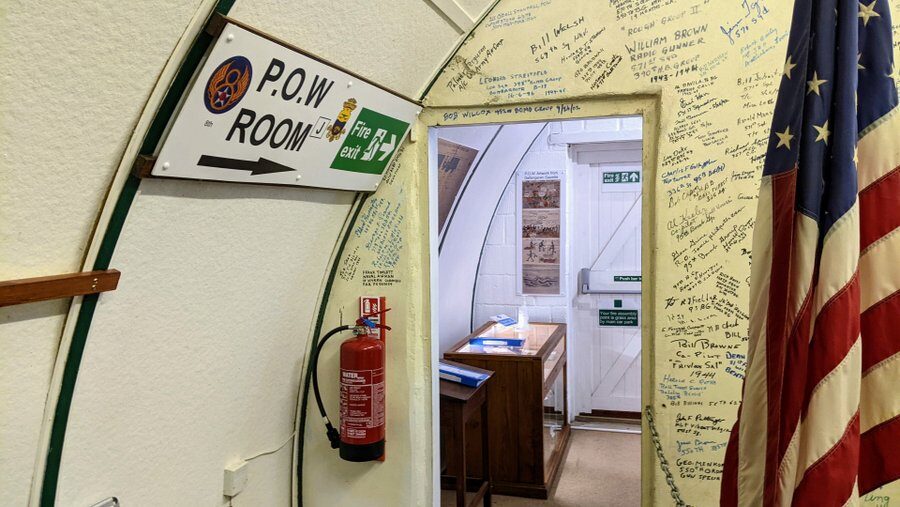

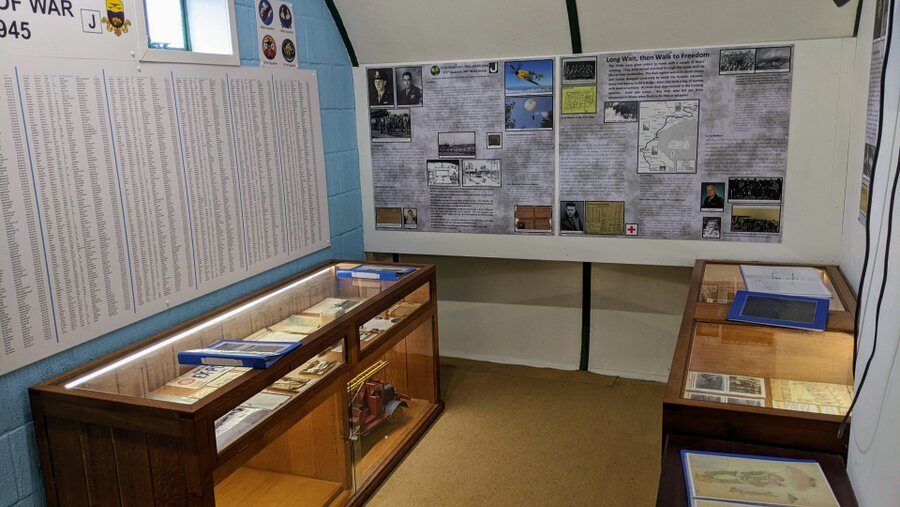

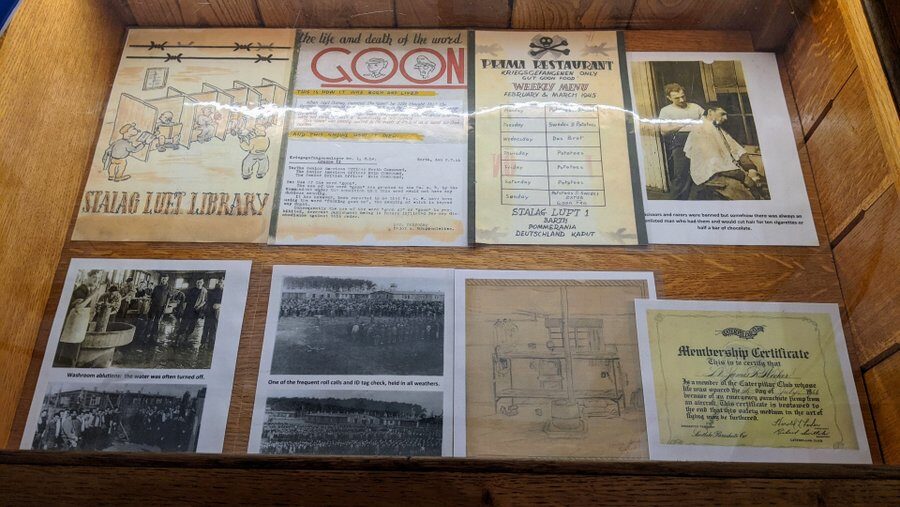

In part of another Nissen hut they have created a Prisoner of War (POW) Room, with records of captured 390th airmen and artefacts relating to captivity, escape and evasion.

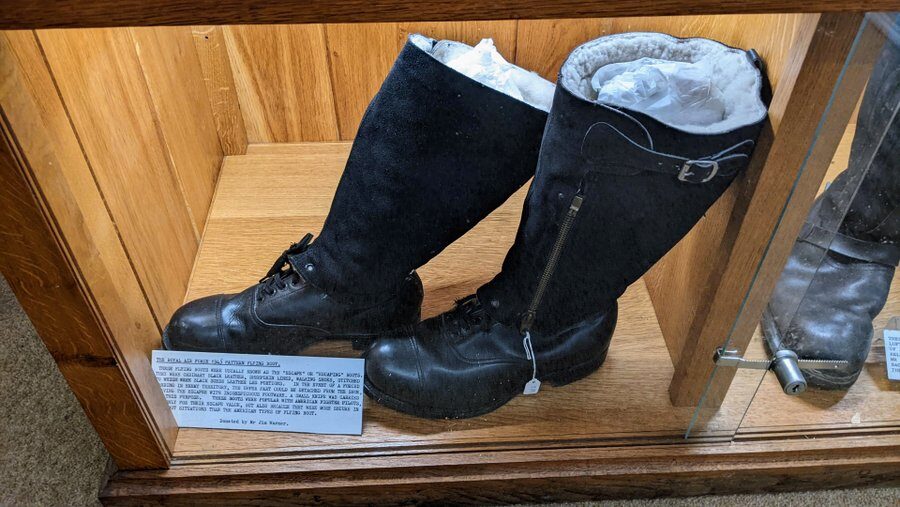

The artefacts include a pair of escape boots – fur-lined flying boots with detachable tops so they can be turned into a normal pair of inconspicuous black shoes for downed airmen evading capture. More correctly known as RAF 1943 Pattern Flying Boots, these were preferred by American fighter pilots to the USAAF issue flying boots. There’s a pair of these up at the National Museum of Flight, Scotland.

In the ground floor rooms of the Control Tower and surrounding spaces, there’s a lot of equipment and ‘wreckology’ on display.

There are a couple of rather poignant pieces of wreckage…

An engine and bent propeller from a 385th Bomb Group B-17 ‘Sleepytime Gal II’ flown by Capt John Hutchinson. On the 21st Feb 1944 he was the lead pilot in a flight of three B-17s returning to their base at Great Ashfield from a raid on Diepholz¹ in Germany. There was a dense layer of cloud covering the approach to their base and the Group Commander ordered that the group should descend through it in flights of three in close formation so they didn’t lose each other. Hutchinson was leading Lt Eugene St. John on his left wing and Lt Pease on his right.

On the way down, Pease got separated, and shortly after they broke out of the cloud, Pease emerged diving at speed behind Hutchison. He passed under Hutchison and then over-corrected, rising up under Hutchinson between the fuselage and No. 3 engine. The engine’s propeller sliced the aft section of Pease’s aircraft off and both aircraft plunged to the ground killing all 21 men on board.

What was poignant about it? Hutchinson and his crew were returning safely from their 25th mission – their last mission before returning to the USA. Lt St. John, whose report describes the accident remembers seeing Hutchison flying with a celebratory cigar in his mouth just before the collision.

Oh, and why 21 men? B-17s flew with 10 crew, but Hutchinson was also carrying a photographer on this last mission.

The other notable piece of wreckage comes from a P-51 Mustang fighter. Again, it is an engine (a Rolls Royce Merlin manufactured under license by Packard) and a bent propeller.

On 26 July 1944 the Mustang was on a training flight when things went wrong and it plunged to the ground near Walberswick in Suffolk, killing its pilot, Lt Richard Bennett. What makes such a loss particularly sad, is that Bennett had been flying fighters for only four weeks… having completed 30 missions as a B-17 bomber pilot with 457th Bomb Group.

In one of the rooms there’s a set of turrets…

Martin A-6-A tail turret Martin A-6-A tail turret |

Martin A-3-B Mid-upper turret Martin A-3-B Mid-upper turret |

Frazer-Nash FN7 Mid-Upper Turret Frazer-Nash FN7 Mid-Upper Turret |

The Martin turrets were used in B-24 Liberators. The Frazer-Nash turret was a British turret used on Short Stirlings. I always like turrets, though I can’t imagine spending hours cramped up in one! The Yorkshire Air Museum has a good collection of them.

Up in the first floor control room there are a set of photographic displays and some aircrew flight jackets.

And on the roof, there’s a good view of what little remains of Station 153 – Framlingham, and inside the Visual Control Room (VCR), a map showing what had been there.

The Museum of the British Resistance Organisation

In one of the larger buildings on the site attached to the Control Tower, is the Museum of the British Resistance Organisation, a secret army of ‘Auxiliary Units’ – a purposefully bland name giving no indication of their role – set up in July 1940. (On names: the British Resistance Organisation is not a good one because it does imply a role, and not an accurate one.)

The Auxiliary Units, sometimes called GHQ Auxiliary Units or “Auxiliers”, were local men ** in Britain, secretly trained to go underground (literally) in the event of a German invasion and create disruption by sabotage and assassination behind enemy lines.

They operated as teams of 6-7 men, from secret underground bunkers called “Operational Bases” (OBs) built mostly in the coastal regions from the northeast of Scotland, down the North Sea coast, around East Anglia, Kent, the south coast and southwest, and then around up to Pembrokeshire. The idea was to place them where they would be behind an enemy invasion force’s lines, from where they could report enemy dispositions to British forces, and disrupt them.

In all there were thought to be around 500+ OBs. After the war the Royal Engineers were tasked with demolishing them, so they couldn’t cause injury or be used as hideouts by criminals, but it’s likely that many remain undiscovered.

The Auxiliers were part of the secret services, just like SOE and SIS (MI6). Like their counterparts at Bletchley Park they were sworn to secrecy, and many took their secrets to the grave, which is why we know so little about them.

Interestingly, as the threat of invasion diminished, so did the need for Auxiliary Units. Some of them moved into other branches of the special/secret services. In 1943, Col. Paddy Mayne the Commanding Officer of 1st Special Air Service (SAS) – yes, him, featured in the recent SAS Rogue Heroes TV series – called for volunteers from the Auxiliary Units to join the SAS. At a secret gathering at the Curzon Cinema in Leicester Square he was abble to sign up around 400 men.

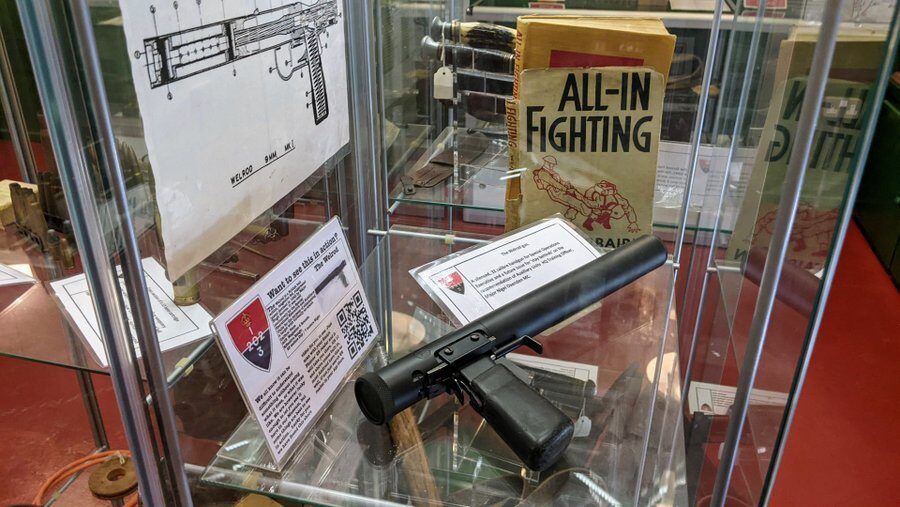

The museum houses many photos and documents, as well as the ‘tools of the trade’ available to the Auxiliary Units, such as knives, guns, explosives, and other devices.

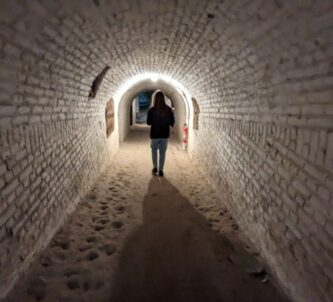

Most importantly, down some steps, they have recreated an Operational Base. The replica bunker is a reconstruction of an underground hideout used at nearby Stratford St Andrew, Suffolk, which had been abandoned in 1944.

In 1992, Herman Kindred, ex-Sergeant of the Stratford St Andrew patrol, set off to quietly inspect his old OB. The local farmer had already discovered it and Herman was persuaded to tell his story to the media. This triggered the creation of the Museum of the British Resistance Organisation, which opened in 1997.

¹ https://www.385thbga.com/records/index-mission-number-to-date-and-target-2/mission-summaries/

* I’ve read somewhere, but can’t find the reference now, that since “Parham” sounds similar – especially over the radio – to “Horham”, another USAAF base nearby, they chose the name “Framlingham” to avoid confusion. And not just verbal confusion. I’ve just discovered I wrote “Parham” in a heading on my Horham review published 6 months ago!

** And women, in the Special Duties Branch where they worked as civilian spies and radio operators.

Declaration: None needed. I was visiting the area.

Factbox

Website:

Parham Airfield Museum

(The 390th BG Association also have a memorial museum co-located on the site of the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona.)

Getting there: Parham Airfield Museum

Parham Airfield

Parham

Framlingham

IP13 9AF

Suffolk

Best to get there by car. The museum is 4 miles south-east of Framlingham, via Parham. There’s plenty of parking space on site.

Public transport options are limited. Coming from London there’s a Greater Anglia rail service from London Liverpool Street to Wickham Market, which is a 4 mile/10 minute taxi ride away.

Entry Price:

FREE

As with most memorial museums, there is no entry fee. So they try to raise money from donations and from the café/shop, and again, as with most airfield memorial museums, they have an excellent range of second hand military history and aviation books on sale at cheap prices. I should think almost a fifth of my library is sourced from museums like this. I always come away with a small pile of books. It’s a win-win; I find all sorts of unexpected books to fill my shelves, and they gain much needed revenue.

Opening Hours:

The museum hasn’t published its opening days/hours for 2023 yet.

If it follows the pattern of 2022, you can expect it to be open between 11.00 – 17.00 on Sundays and Bank Holiday Mondays from the beginning of April to the end of October.

During the summer months June – August it is also likely to be open on Wednesdays 11.00 – 16.00.