Twelve days ago, 16 sailors in small yachts set out from les Sables d’Olonne on the French Atlantic coast to race around the world, non-stop and single-handed in the 3rd edition of the Golden Globe Race.

There’s nothing particularly unusual about that. There are a number of crewed round-the-world races these days and the Vendée Globe race, held every four years from the same harbour, has solo sailors flying around the world non-stop in ultra-high-tech, foil-skimming yachts in as little as 74 days.

Here’s the difference: the Golden Globe Race (GGR) competitors probably won’t be seen back in Les Sables d’Olonne for another 280+ days at their current rate of progress. That’s May/June 2023.

.

Golden Globe Race – The Golden Age of Solo Sailing

Photo: MaryAnnesFrance.com

Why so slow? The GGR is a reincarnation of the original Golden Globe race organised by the Sunday Times newspaper in 1968 and won in 313 days by Robin Knox Johnston (now ‘Sir Robin’) in his boat, Suhaili. Not only did he win the race, he was the only competitor out of nine, to finish. As the current GGR website bluntly puts it, “The rest either sank, retired or committed suicide*.”

Fifty years later in 2018, the Golden Globe Race was resurrected, and to the original standards.

Boats have to be glass-fibre production boats (min 20 built) between 32ft and 36ft overall (9.75 – 10.97m) designed prior to 1988 that have a full-length keel with rudder attached to their trailing edge – no carbon fibre hulls, kevlar sails or slender foils.

Competitors can only use equipment that would have been available to Sir Robin on board Suhaili. That means no GPS, no digital equipment, no radar, no mobile phone. If a competitor wants to listen to music, it’ll have to be on cassette! Navigation, on paper charts, is by trailing log, RDF signals (Radio Direction Finding), and sextant. Position lines have to be worked manually. Scientific calculators are banned. This is ‘old school’ sailing.

Golden Globe Race – Old School Navigation

Unfortunately for GGR racers, some of the navigation technology that was available in 1968 no longer exists**. The Decca navigation system, which I used in the 1980s, and Loran C were hyperbolic radio navigation systems based on chains of shore-based transmitters. They covered large chunks of the world’s oceans, especially the ‘busy’ parts, and could pinpoint a ship’s position to within a nautical mile. Loran C didn’t become commercially available till the 1970s, but Decca would have been available to Robin Knox Johnston, though I doubt he could have afforded it. He was on a budget***.

The only 1968 electronic tech still available to GGR sailors is RDF – Radio Direction Finding. Back in 1968 RDF transmitters (“beacons”) were plentiful. They were scattered along coastlines and most lighthouses had a beacon. They were cheap and simple to use. You set the frequency of a beacon on your handheld unit, listen for the morse code identifying letters and the following tone. Then you turned the unit till you found the null point in the signal (when the tone disappeared) and read off the bearing on the compass mounted on top.

GGR skipper Guy Waites told me that there were only two beacons covering the route of their pre-GGR race from Gijon in northern Spain across the Bay of Biscay to Les Sables d’Olonne. He managed to find a signal from one of them but not the other. However, GGR sailors don’t give up that easily. He tuned to BBC Radio 4 on 198 longwave, found the null spot in the signal and was able to use that as a second bearing because he knew the transmitter is in Droitwich!

Most of the sailors will rely principally on ‘dead reckoning’, especially when cloud cover prevents them from taking a sun or star sight. You know what course you are steering. Chuck something visible over the stern (I used to use orange painted blocks of hardboard) and after a while take a bearing on it with your handheld compass. Subtract 180° from it and compare it to your ship’s compass… and you have your angle of drift, and thus your true course (we’ll leave tides out of it for the moment). Now all you need to know is how far you’ve travelled.

All the GGR racers will be using a trailing log. There’s a long length of rope with a spinner on the end of it. The rotating rope is attached to a mechanical reading device on the stern of the boat that displays the speed and distance.

But here’s another problem area. The spinner can attract seaweed and needs checking from time to time or else it will slow up and give a false reading. Worse, the twirling spinner sometimes attracts large fish, sharks especially, and can be bitten off! GGR rules stipulate that a competitor must carry at least two spare spinners, but most ocean sailors don’t risk leaving the log out for long periods. They prefer instead to ‘soak’ it for a short period, take a reading, and then assume a continuous rate of progress until there’s a significant change of conditions, or wind, or a course change, and then they’ll soak it again.

Guy Waites says, for those reasons, he rarely uses his log: “I just look at the water running by the hull and I have a pretty good idea of boat speed”.

That leaves the trusty sextant… as long as the weather is clear enough.

treasured possessions. I always

used to think of it as the ‘key to the universe’.

With this I can navigate the the world.

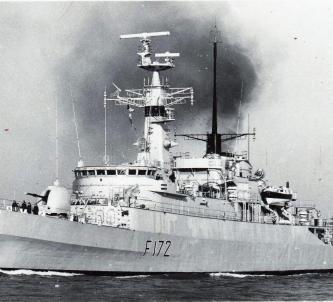

When you are a navigating officer on the bridge of a ship, gliding along 40 metres above the waterline, if you ever resorted to using a sextant (!), you could be pretty sure to get a reliable sight (assuming the sextant is properly calibrated and you’ve applied all the corrections).

When you are 3 metres above the waterline, being thrown about in a small boat in the Southern Oceans with 8 – 10 metre waves, it’s a different matter! (The waves in the Southern Ocean have got bigger since Robin Knox Johnston sailed through them, by the way ¹.) Of course, nobody is looking for pinpoint accuracy in those conditions. If you get within 25 sq miles you’ll be doing pretty well.

Apart from the classic and simple ‘Sun Sight at local Noon’, which immediately gives you your latitude, all other sights on the sun, stars, planets or the moon, rely on accurate time – especially the moon. (I avoided moon sights. It’s an awkward b*gg*r! Fast moving, seconds count, and you have to make lots of adjustments!) So, you need an accurate timepiece; a chronometer.

“But a lovely traditional chronometer in a wooden box is very expensive”, says Guy Waites. “I’ve just got two mechanical wrist watches. They rely on movement to keep them wound up”. Under race rules, competitors can’t use battery watches, which means quartz watches are out. “Which is why the time signal on HF radio is so important”, says Guy.

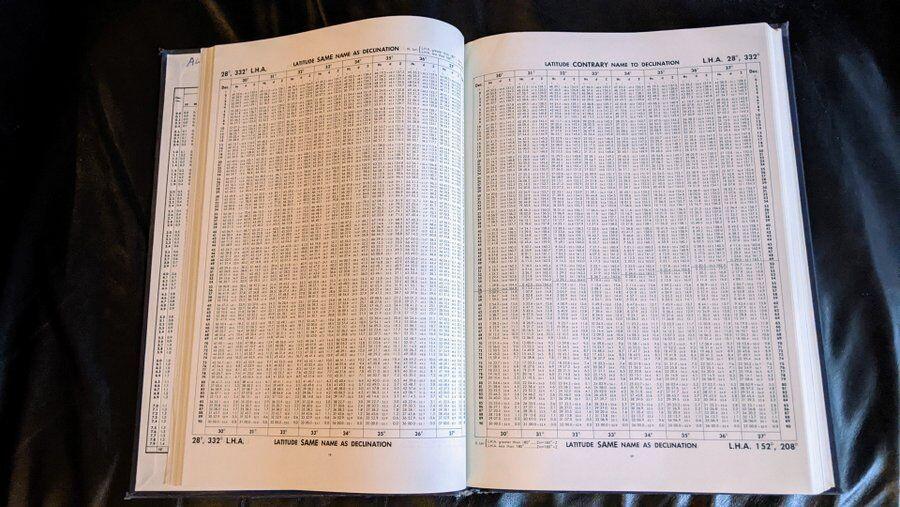

Now, armed with a sight and the time it was taken, it’s time to plot a position line on your paper chart. But, with calculators banned, there are no shortcuts here either. Guy, and most other competitors carry an Almanac and four hefty volumes of Sight Reduction Tables for the Latitudes 0°-15°, 15°-30°, 30°-45° & 45°-60° covering their route.

All the calculations and applied corrections are worked out by hand on a piece of paper, usually a printed A4 form. It’s a far cry from watching your pinpoint accurate position on a rolling digital chart.

Is anybody watching your pinpoint accurate position on a rolling digital chart?

Golden Globe Race – Tracking Competitors on the Route

The GGR skippers may not know where they are precisely, but we and the race organisers do. They are being GPS tracked continuously and a ‘live’ map of their positions is updated every few hours.

The 30,000 mile race course is an east-about circumnavigation starting and finishing in Les Sables-d’Olonne. Along the route there are waypoints and landmarks they must pass to one side or the other. There also four drop off points**** where skippers rendezvous with race officials, family & friends, and drop video footage, letters and things as they pass. There is no physical contact.

Although, as far as the skippers are concerned, they are sailing with only vintage gear, there is some high tech gear on board for safety and media/publicity needs.

The video footage they drop off en route is recorded on hand-held and fixed video cams on the boat. Their ‘Race Pack’ contains: a two-way satellite short text paging unit (to race headquarters only); two handheld satellite phones for up to four short messages per day; a sealed box with two portable GPS chart plotters (for emergency use only).

Two important concessions are:

- a weather fax system. Skippers can receive World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) High Seas Text weather forecasts and HF Radio Weather-Fax forecasts, but no other weather predicting services.

- a marine Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponder & receiver. This identifies you on radar to nearby ships (skippers can’t see their own location) and alerts you if you are ‘pinged’ by a nearby radar.

The latter may not be entirely reliable. A few days ago a strange sound brought Guy de Boer rushing from the cabin into the cockpit (gashing his leg on the way) where he was confronted by an 80 ft fishing vessel right in front of him. He grabbed the tiller and swerved missing the ship “by 15ft” (4.5m). A close call! He knew his AIS had a damaged knob and could be unreliable, but the fishing skipper should have been alerted and identified him on radar.

Given the uncertainties and dangers, WHO DOES THIS?!

Golden Globe Race – Competitors

Sixteen sailors and their boats eventually passed all the race entrant requirements and met the scrutineer’s exacting standards. They set off from Les Sables d’Olonne on 4th September.

What’s interesting is that there are only three – Elliott Smith 27, Kirsten Neuschäfer 39 & Damian Guillou 39 – who are under 40 years old. The rest are (and I hope they’ll forgive me) grizzled old men of the sea! The average age was, until the oldest Edward Walentynowicz 68 retired a few days out, 53½ yrs. They match the age of their boats almost perfectly!

| The Golden Globe 2022 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sailor | Nationality | Boat/Race No. | Age |

| Jeremy Bagshaw | South Africa | Olleanna (07) | 59 |

| Ertan Beskardes | UK | Lazy Otter (94) | 60 |

| Guy de Boer | USA | Spirit (56) | 66 |

| Simon Curwen | UK | Clara (04) | 62 |

| Arnaud Gaist | French | Hermes Phoning (11) | 50 |

| Michael Guggenberger | Austria | Nuri (17) | 44 |

| Damien Guillou | French | PRB (85) | 39 |

| Ian Herbert-Jones | UK | Puffin (37) | 52 |

| Pat Lawless | Ireland | Green Rebel (22) | 66 |

| Tapio Lehtinen | Finland | Asteria (06) | 64 |

| Kirsten Neuschäfer | South Africa | Minnehaha (53) | 39 |

| Mark Sinclair | Australia | Coconut (88) | 63 |

| Elliott Smith | USA | Second Wind (24) | 27 |

| Abhilash Tomy | Goa,India | Bayanat (71) | 43 |

| Guy Waites | UK | Sagarmatha (13) | 54 |

| Edward Walentynowicz | Canada | Noah’s Jest (34) | 68 |

| Average age: | 53½ yrs | ||

| Based on a table compiled by Mary Anne’s France | |||

It takes an extraordinary mental & physical resilience to spend the best part of a year completely alone at sea. Why do they do it? Well, all will say they want to win but that’s not the main reason. Some may talk about testing themselves, but for the majority it’s about ‘getting in the zone’; just being at one with yourself, the ocean and your boat.

Irishman, Pat Lawless, says it’s almost a spiritual thing.

He has one item on board that no other competitor has – a wood burning stove!

“I’m a bit of a pagan, a druid”, he explains, “and I’m surrounded by the elements”.

Water and Air are outside, he says, “and the element of Fire is in the cooker and the engine… but the real element of Fire is in my stove, and that’s why I love it”.

What about the fourth element?

His Earth is his boat, with whom he has a real bond. “You talk to it, and it talks back to you through the sounds it makes as waves hit and the wind changes. You know it’s an inanimate object but you talk to it”.

As comfy as it might be to have a wood burning stove in the southern latitudes, what on earth (back to his analogy!) is he going to burn? Well, he’ll only use it maybe once a week when it’s cold, and on Christmas Day, and there always little bits of burnable rubbish about the boat such as packaging on his supplies… and, we both joke, it’s a good place to dispose of all those Sight Reduction forms where he gets the sums wrong!

There is a downloadable 63-page PDF with all the Rules of the Race here.

There is a Mechtraveller Guide to Visiting Les Sables d’Olonne here.

* Donald Crowhurst was the suicide. Race account here.

** Although many countries are talking about re-establishing an updated system as a back up if GPS is disrupted.

*** When I asked him if he really sailed around the world with a fixed bladed propeller dragging through the water, he told me feathering props were just too expensive, “I spent my last 17 quid on a length of rope which I trailed behind the boat; it probably saved my life”!

**** Off Lanzerote in the Canaries; off Cape Town; off Storm Bay Tasmania; off Punta del Este, Uruguay

¹ The ocean’s tallest waves are getting taller – Science.org

Declaration: I was on a self-driving trip, visiting Les Sables d’Olonne as a guest of Vendée Tourisme and Les Sables d’Olonne Tourisme.

on the rocks.

UPDATE 18/09/2022: In the early hours of this morning, Guy de Boer in his boat Spirit, hit rocks 50 metres from the beach on the north west coast of Fuerteventura. Rescue services were able to come to his aid and he is safe and well. His boat lies stranded on the shore.

It raised a discussion about the need to bring sailors using old navigation techniques, close to the shore for film drops. Many comments focused on the danger of approaching land at night. Whereas the opposite is true. The BEST time to approach is while it is still dark so you can pick the loom of lighthouses (each identifiable) and get a fix, or at least a position line, while you are still 30+ miles offshore.

In Guy’s case he had already rounded the mark just next to the marina on the southern tip of Lanzerote, dropped his film and was setting off to go around Fuerteventura with the lights of both islands behind and before him. He had a more accurate idea of his position than he had had for days, and he was less than 8 miles from the large lighthouse of El Toston on Fuerteventura, which he would need to round.

We don’t yet know, how he failed to notice he was drifting inshore (that the bearing on El Toston was increasing and/or the lights of Majanicho were getting nearer), probably due to the current or an unexpected wind shift, but navigating at night near a shore without modern navigation aids is not as dangerous as is being made out. The greater danger is of collision with local vessels.