“It’s definitely not what I was expecting,” said a friend on our visit to the Swarovski crystal manufacturer’s Crystal Worlds. “I thought it would be a little like the Corning Glass brand museum in New York State”.

I know exactly what he meant. I’ve been there. The Corning Museum of Glass is full of examples of domestic & industrial glass products and the history of the company.

Swarovski Crystal Worlds or KristallWelten doesn’t mention the manufacturing process – a secret so closely guarded that the huge Swarovski factory next door has security worthy of Area 51 – nor is there much reference to the history of the small family-firm turned industrial-conglomerate, making costume jewelry.

The history

Essentially, the story goes like this: in 1895, Daniel Swarovski, the son of a Bohemian glass-cutter, built his factory in Wattens, just outside Innsbruck, to be close to the minerals, water, and cheap hydro-electric electricity he needed for production, plus the railway for distribution to Europe’s nearby capital cities.

The demand for cheap jewelry was insatiable and the company grew quickly, and expanded with the addition of two other divisions…

In 1892 he had patented an electric cutting machine that facilitated the production of crystal glass, and in 1919 he created a specialist division, Tyrolit, developing grinding and polishing tools for other markets.

And in 1949, his son Wilhelm launched Swarovski Optik, manufacturing optical instruments such as binoculars and telescopes.

So what is Kristallwelten all about then?

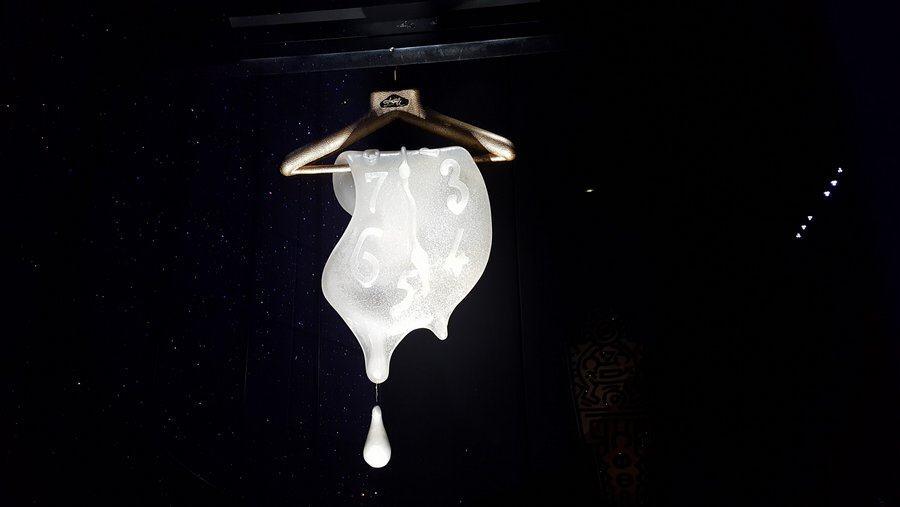

Crystal inspired art.

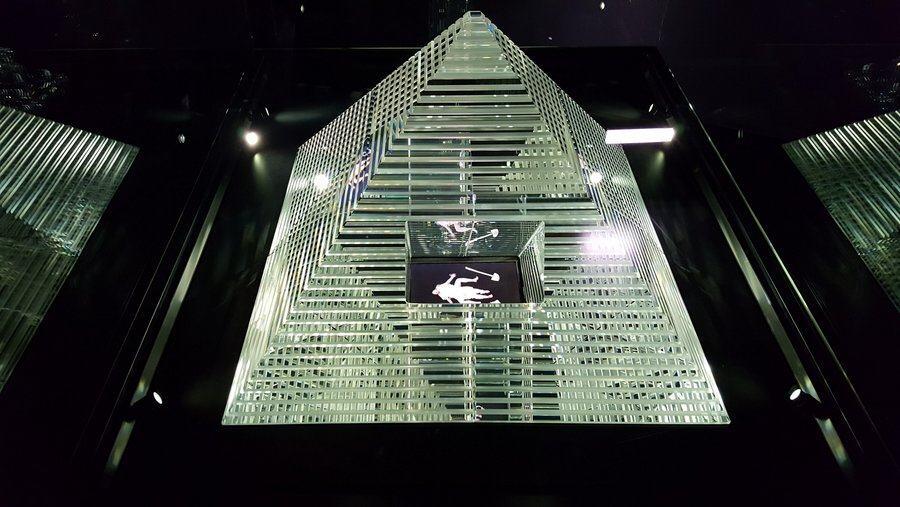

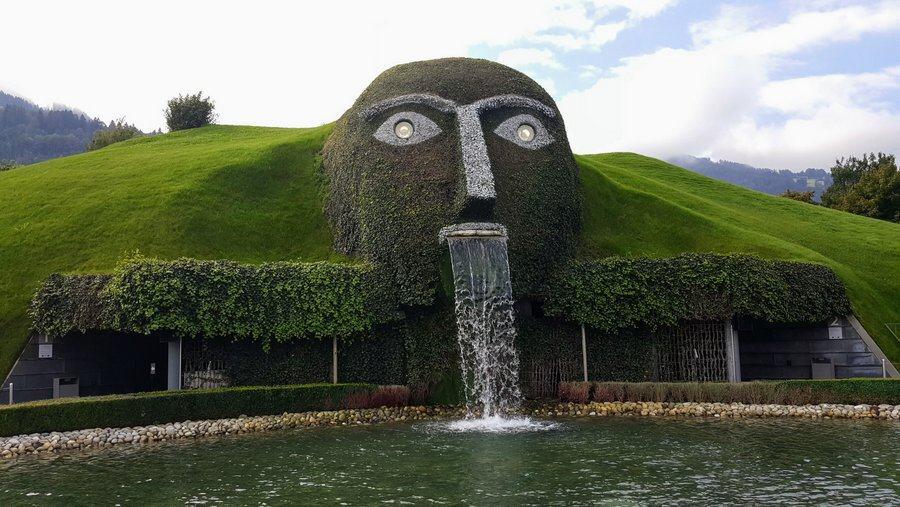

The ‘cave’ opened in 1994. Designed by artist André Heller, it lies under a huge grassy hill and contains a horde of treasures and wonders guarded by a giant whose face we meet at the entrance. Inside is a labyrinth of semi-permanent* art installations and experiences by guest artists in 16 “chambers of wonder”, starting in the ‘Blue Hall’ with artworks by Andy Warhol and Salvador Dali.

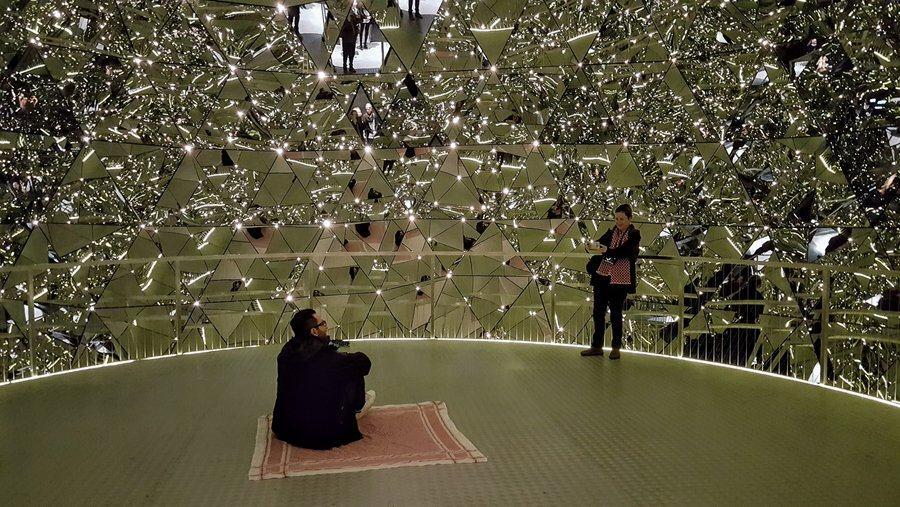

I visited Kristallwelten a year or so after it opened and the only chamber I recognised for sure from then was the Crystal Dome, a geodesic sphere of mirrors (595 of them) that reflect sound and your fractured images back at you.

I’m not sure about Eden by Frederick Stallard – a magical forest of frozen trees that is like a maze. I think that could have been one of the original installations. It seemed familiar, but then it could just be mirroring a common dream of being lost in a sparkling wood!

I loved Mechanical Theatre by Jim Whiting. It melds together his fascination with mechanics and his own life experience. As a child he suffered from rickets and had to wear a steel and leather corset to bed at night. The two elements – humans and technology – feature in various forms in this installation: the striding woman, the body parts assembled into the figure of Adonis, the dancing legs.

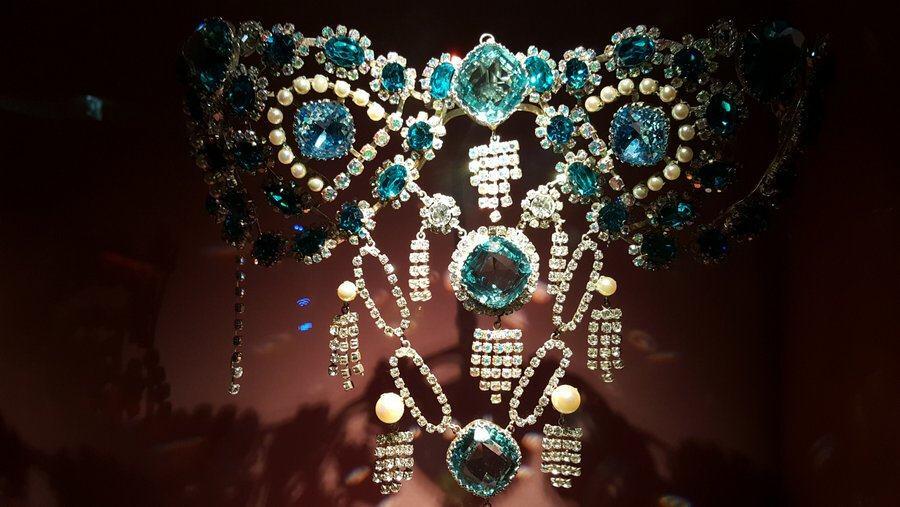

There are a number of chambers to get lost in or confused by, but all have a playful appeal. The last chamber offers a glimpse of Swarovski history with some old photographs of the business and the family, and displays of old costumes, tiaras, necklaces and other fashion items. Finally it all ends with the Swarovski shop.

There is more outside

As part of a big expansion programme between 2013 and 2015, new works were added to the cave and a spectacular attraction added to the gardens outside; the Crystal Cloud, created by Andy Cao and Xavier Perrot, comprising a 1,400 square metre ‘cloud’ of around 800,000 hand-mounted Swarovski crystals drifting over a tranquil lake of water, with a gentle audio soundscape adding to the peacefulness. It’s the perfect space for stressed Swarovski factory workers and Kristallwelten visitors to relax and maybe enjoy a picnic lunch!

Declaration: I was on a trip hosted by Austria Tourism and my visit to Swarovski Kristallwelten was free.