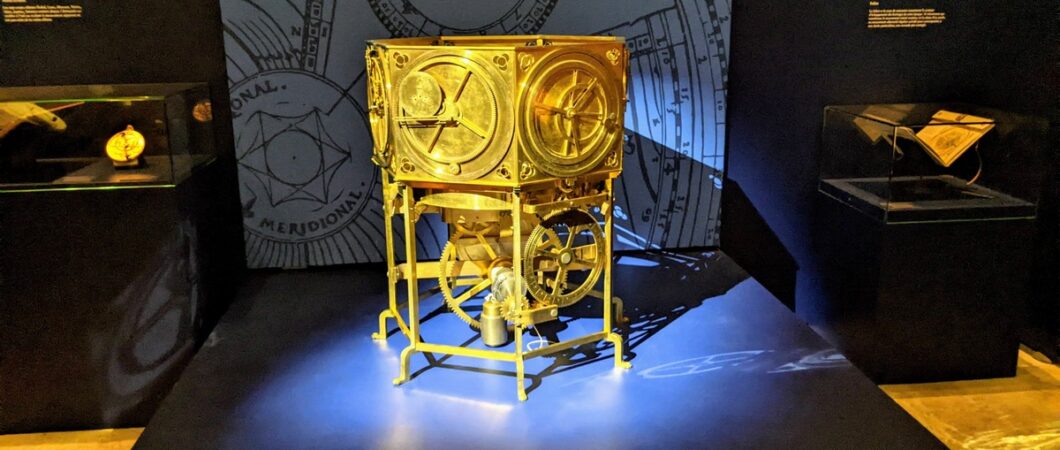

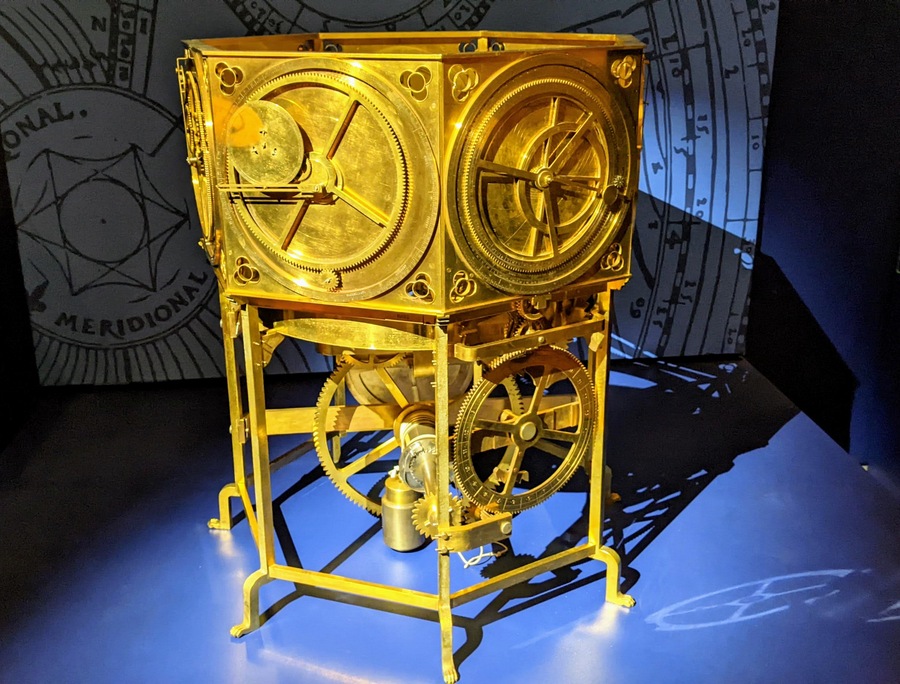

Dondi’s Astrarium is considered to be the very first mechanical planetary clock.

It was designed in Italy at the end of the 14th century by Giovanni Dondi (1330-1388) who created this large brass mechanism, roughly a metre tall, to automate the complex calculations necessary to create horoscopes. During the Renaissance, horoscopes and their interpretation were an important part of prediction and decision-making.

The clock has seven faces on which respectively appear the position of the Moon, the Sun and the five planets known at the time: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. The mechanism reproduces on a small scale what was assumed to be the movement of the planets. Based on Ptolemy’s geocentric system, it testifies to the knowledge of the cosmos in the Middle Ages. The design of this instrument constitutes a true technical feat at a time when clockwork mechanisms were still poorly mastered.

Sadly, this is not the real object. The original Astrarium was lost around the beginning of the 16th century. This is a reconstruction created in the late 1980s by a team of historians, engineers and researchers from the Paris Observatory, based on Dondi’s manuscripts in the library of Padua, detailing the object and its manufacture.

Incidentally…

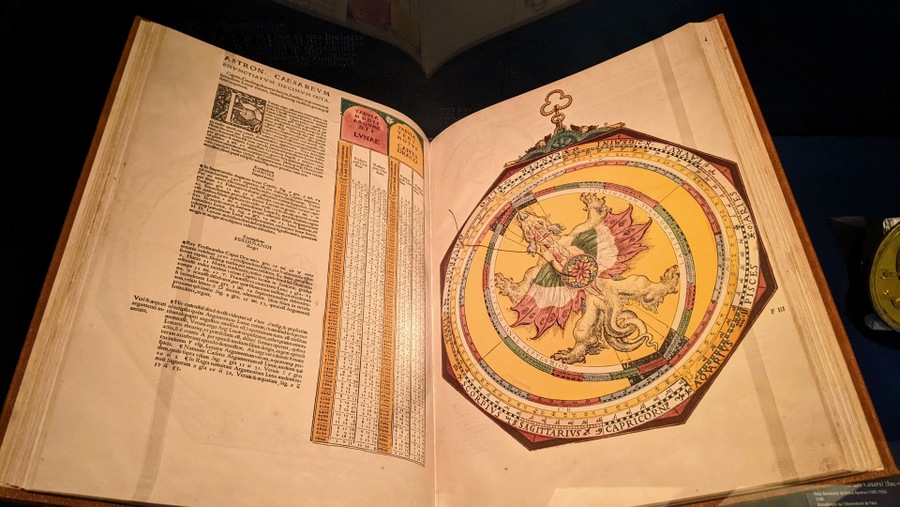

When it was on display in a temporary exhibition* at the Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris, a couple of years ago, it was part of a mini exhibition of medieval astronomical objects including the astrolabe of Arsenius, and a stunning copy of the Astronomicum Caesareum, considered to be one of the great masterpieces of sixteenth-century printing.

This beautifully-illustrated astronomical text was published in 1550 by German Petrus Apianus (1495 – 1552), aka Peter Apian, the court astronomer of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Its most striking feature is the 35 hand-colored woodcut “volvelles”; movable paper circles that allow the reader to calculate astronomical data and planetary movements.

How? Well The Met in New York, have explained it in a video.

Although it was absolutely one of the most advanced astronomical works of its day, just like Dondi’s Astrarium, its data and calculations were based on Ptolomy’s view of the heavens in which the sun and everything else revolves around the Earth… Wah, Wuh! Within three years, Copernicus had blown that theory out of the sky, and Peter Apian’s book became simply an artwork. It’s estimated there may still be around 120 copies of Astronomicum Caesareum in university libraries, museums and private collections.

* is part of the Musée des Arts et Métiers collection, but not on permanent display.