With the upcoming Masters of the Air mini-series due for release soon****, the Memorial Museum for the USAAF 100th Bomb Group at their former base at Thorpe Abbotts in Norfolk, is likely to become the focus for a lot of attention.

Masters of the Air is the third in Tom Hanks & Stephen Spielberg’s WW2 drama series after ‘Band of Brothers‘ and The Pacific. It is based on Donald L. Miller’s book of the same name and tells the story of the U.S. 8th Air Force bomber crews over Europe in World War II, focusing on the exploits of the 100th Bombardment Group and two of its B-17 ‘Flying Fortress’ squadrons in particular, the 418th and 350th, based at Thorpe Abbotts.*

USAAF 8th Air Force Memorial Museums

| 100th Bomb Group Museum – Thorpe Abbotts | 95th Bomb Group Museum & Red Feather Club – Horham |

| 390th Bomb Group Museum – Parham Airfield | 446th Bomb Group Museum – Flixton (at NSAM) |

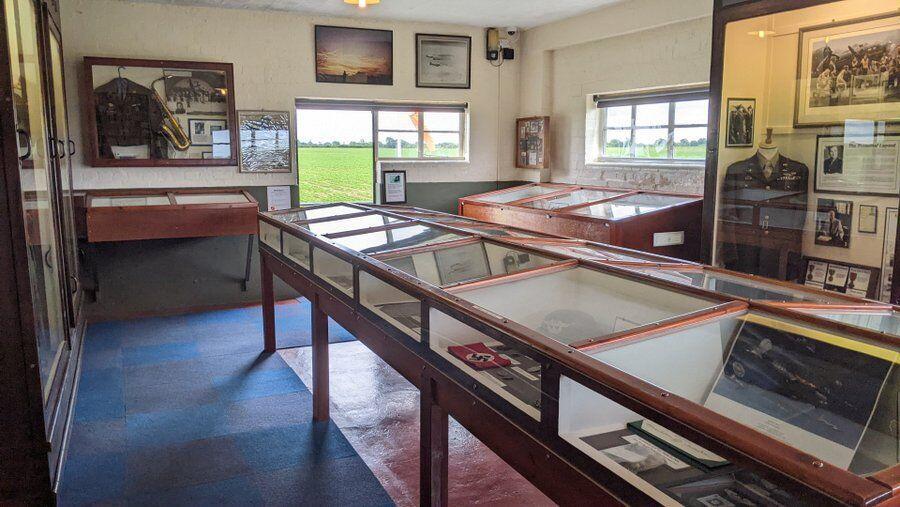

The museum itself is not very large, but it has some really interesting and evocative artefacts, and the centrepiece, its lovingly restored control tower, is a Grade II listed building¹ in a historic location. From it, you can survey most of the 600 acre (243 hectare) airbase – it’s still all agricultural land.

Station 139 (Thorpe Abbotts) was home to the 100th Bomb Group’s four squadrons of B-17s: the 349th, 350th, 351st, and 418th. That was roughly 70 aircraft and 3,500 personnel.

Construction began in 1942 and the last American serviceman left the base in December 1945. The first bombing mission (Bremen submarine pens) took place on 25 June 1943. The last (Oranienburg) was on 20 April 1945. Between those two dates – less than two years – the ‘Bloody 100th’ flew 8,630 sorties (306 missions) dropping 19,257 tons of bombs (plus 137 tons of supplies). They lost 229 aircraft and 768 men KIA/MIA. 939 aircrew became prisoners of war.

That’s why Thorpe Abbotts is a ‘memorial’ museum. It is a placeholder for the intense emotions and brief memories of all those servicemen, their families and their descendants.

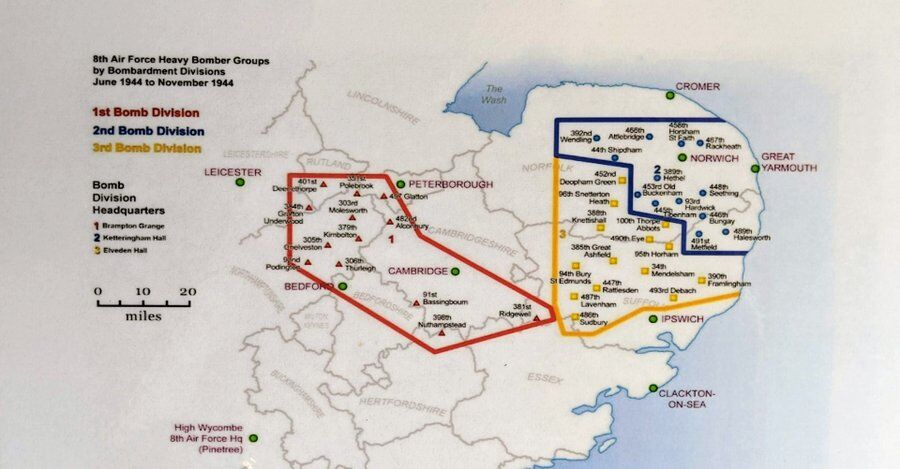

It’s amazing to think that this huge airbase was just one of dozens being built in Norfolk alone between 1942/43.

Thirteen and a half thousand engineers, supported by 32,000 civilian workers had built or converted 50 bomber & fighter airbases for the 8th Air Force by the end of 1943. By D-Day (June 1944) there would be an airbase every eight miles on average in East Anglia!²

Post-war Thorpe Abbotts

When the last Americans left in 45, the base was handed over to the RAF. Some buildings were used for storage from time to time, but it was mostly left to deteriorate, and in April 1956 the land was handed back to the original landowner.

In the 1960/70s the two main hangers and many buildings were demolished. The runways and perimeter track were also torn up so the land could return to agricultural use. But in 1977 a local man, Mike Harvey, decided something at least should be preserved as a memorial. Together with a local group of enthusiasts he negotiated a 999-year lease from the landowner for the control tower and surrounding land, and they set about restoring it. The museum was opened in May 1981. Over the next few years they extended the ‘Engine Shed’ building, and added the ‘Sad Sack Shack’ (I still don’t know how that name came about! If you do, tell us in the comments.) and the ‘Varian Centre’ using WW2 Quonset hut materials sourced from other airfields. Michael Harvey died in 1995, but not before he had seen the museum used for reunions by many veterans and their families in 1986, 1988 and 1992.

The 100th Bomb Group Museum Today

Feature photo shows the Varian Centre on the left, the control tower in the centre, and on the right the small Quonset hut is the Sad Sack Shack. You can see the corner of the Engine Shed behind it.

The Varian Centre

The Varian Centre, named after (and opened by) Major Horace Varian, Secretary of the 100th Bomb Group Association** in the USA and former Group Adjutant, is the entrance and main visitor facility for the museum. It has a few artefacts but it’s primarily a shop, café and toilets.

The museum has always had close ties with the 100th Bomb Group Association, whose members helped raise funds for the museum, and have visited often.

Sad Sack Shack

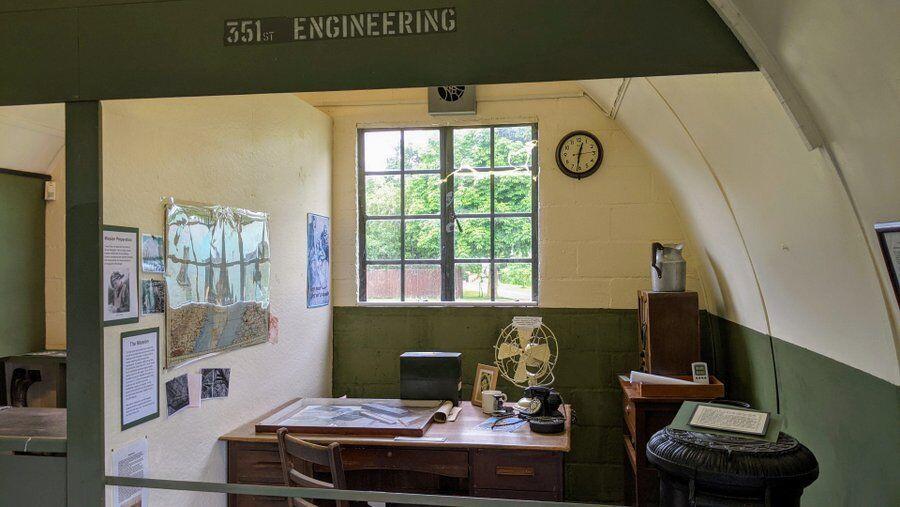

The centrepiece of the shack is a model case with many of the 8th Air Force aircraft, but the shack also has a couple of recreated ground crew/engineering offices.

The typical ground crew for a squadron would consist of the Squadron Engineering Officer; under him a Flight Chief and a number of Line Chiefs supervising 48 aircraft and engine mechanics; 2 aircraft inspectors; 5 electrical mechanics; 4 instrument mechanics; 2 propeller mechanics; 2 sheet metal workers; 2 welders; 2 motor transport mechanics; 8 specialist vehicle drivers; 1 carpenter; 5 clerks; 1 supply technician. There was also an armaments section with weapons & armaments technicians including 4 power turret specialists.

Given the kind of damage that squadrons were experiencing on missions, that doesn’t sound like nearly enough ground crew to me!

One thing worth looking at. There’s a cabinet with a piece of undercarriage from a ‘Project Aphrodite’ crash – one of the few larger parts left after the huge explosion of a remote-control B-17 packed with explosives. One of the 100th BG technicians, Elmer Most, was involved. He parachuted to safety. The pilot – they were there to get the aircraft airborne and armed before jumping out – didn’t.

The Aphrodite Project and its US Navy counterpart, Project Anvil, didn’t have an encouraging track record. President Kennedy’s elder brother, Joseph Kennedy Jnr, was killed in a huge Project Anvil explosion over Blythbrugh. There’s a memorial in the church there. Donald Miller describes the Aphrodite & Anvil missions in ‘Masters of the Air’.

Engine Shed

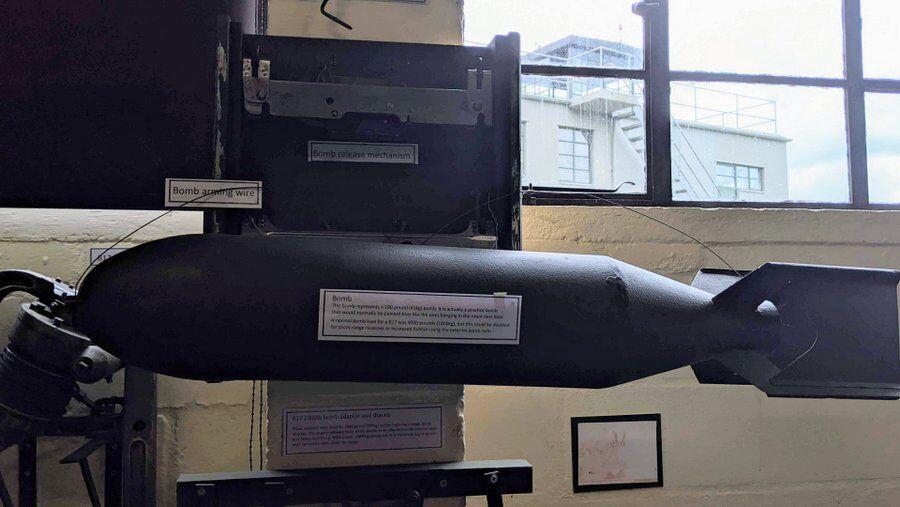

“And what happened if he wanted to go to the toilet?” That got their attention.Next to the control tower, the original night-flying equipment store has been extended and houses a number of interesting items. There are some photographic displays and accounts of Bloody 100th missions, like the Münster Raid on 10 Oct 1943. Most of the items in here focus on engineering and armaments. It gave me a chance to study the way different bomb loads were rigged in the bomb bays and how they were attached via their bomb shackles to the bomb racks.

They also have a couple of turrets – a tail turret from a B-24 Liberator and a B-17 ball turret. While I was there, there was a family of young kids very excited by the ball turret with its mannequin gunner.

“How long did he have to stay scrunched up in there?” asked Deputy Curator Reg Wilson as he came into the room. “Up to ten hours”, he said, answering his own question.

“And what happened if he wanted to go to the toilet?” That got their attention. “He just had to pee in his pants!”

“When we get home, you have to go sit on the sofa and not move for just one hour”, said their mum. “Let’s see if you can manage it”. I think they went home with a healthy respect for B-17 gunners!

In the corner of the shed is an unremarkable ammunition trolley, but I rather like how it got here.

The 4-wheeled trolleys used to haul supplies and ammunition around the Thorpe Abbotts base had iron-rimmed wheels. The din they made on rough concrete taxiways was not welcomed by engineers trying to snatch a few minutes/hours of sleep in the tents out at the hardstands (there’s one erected outside), so they came up with their own solution. They salvaged a set of 4 tail wheels from damaged B-17s and built a ‘silent’ truck… which wasn’t returned with the rest of their equipment to the USA at the end of the war, because it did not appear on the inventory!

Here’s something I hadn’t heard of before; a rather uninspiring piece of concrete right outside the Engine Shed.

It turns out this is a Pickett-Hamilton Fort, or the top of it at least. These were pop-up pillboxes for airfield defence in the event of an attack. The two to three-man pillboxes were sunk into the ground around the runways (usually three per runway) and could be raised 2½ft (0.76m) above the ground by a hydraulic pump, no doubt surprising any attackers! The men entered through the metal hatch at the top and once raised, could fire their rifles or machine guns through three slits. When not needed, the pillboxes were retracted into the ground so they weren’t an obstruction to aircraft. Of course, in the end there was no German invasion of Britain and no ground attacks on airfields, so they were never used in action.

This one came from RAF Martlesham Heath and was later installed at the Thorpe Abbots museum.

Control Tower

The ground floor has a number of interesting displays and exhibits including a Norden bombsight (there’s always one of those!), a B-17 flight deck mock-up, and a collection of radio and aerial photographic equipment. All bomber airbases had a photo lab with 20+ personnel to quickly process bomb damage images.

But I spent most time with the crew of Squawking Hawk II.

In a ground floor office with mannequins wearing some of their dress uniforms, there are a set of laminated documents detailing the bomb mission to Stuttgart on 6 Sep 1943, the attack by Luftwaffe fighters, and the individual crew members themselves.

It’s fascinating stuff. Not all the crew survived, but thanks to their heroic efforts they managed to nurse their crippled plane back to England.

The first floor has photo displays and memorabilia of air crews and ground crews on the base, and a collection of air crew flying jackets.

In the Watch Office³ (the control room at the front) there is a display case recalling the day in 1944 when Glen Miller and his band came to play at the base. There are also displays of escape and evasion items used by downed airmen, such as ID documents, maps and German, French & Italian bank notes. Quite a few (75+) 100th BG aircrew managed to evade capture, but many more, over 900, didn’t. Many of those ended up in Stalag Luft III outside Sagan (now Żagań, Poland).

From the Watch Office you can walk out onto the balcony on the second floor and around the building to the stairs leading up to the roof and the glass control box – sometimes called the “cupola”, usually called the Visual Control Room (VCR). It would be used to monitor the weather, air traffic and for airfield security & emergency response. The officers and servicemen/women in the Watch Office could see and control ground traffic, but they couldn’t see behind them. The VCR staff had 360° views. They could see what was in the air around them, above them, and for example, direct emergency vehicles to a crash off site.

It still has those panoramic views. From here you can see pretty much the whole of the former airfield (it’s an enormous area), and in the centre of the room, for reference, is an excellent table top model of the base as it was in 1943. The control box also has some original communications and weather equipment on display.

In a nice touch, you can hear periodically the sound of propeller aircraft passing overhead. It’s realistic enough that I’m told visitors will often walk outside and look up to see what’s up there!

Outside the control tower is a memorial to General Curtis LeMay, Commander of the 3rd Air Division of the USAAF 8th Air Force***. After a long career that included commands in the Korean, Vietnam and Cold Wars, LeMay died in 1990.

* Donald Miller’s book, Masters of the Air ![]() , covers the whole USAAF bombing campaign, but he brings aspects of it to life by focusing on individual servicemen. The opening chapter starts with Major John Egan (played by Callum Turner in MOA), the commander of the 418th Bomb Squadron, taking some well earned leave in London.

, covers the whole USAAF bombing campaign, but he brings aspects of it to life by focusing on individual servicemen. The opening chapter starts with Major John Egan (played by Callum Turner in MOA), the commander of the 418th Bomb Squadron, taking some well earned leave in London.

The other leading real-life character is Gale W. Cleven, commanding officer of the 350th Bomb Squadron, played by Austin Butler. Both Cleven and Egan were nicknamed “Bucky”, both were squadron commanders and friends, both were shot down within two days of each other, and both survived to meet up later in the same POW camp!

Other likely real-life characters include crew members, senior officers, station personnel and mechanics.

It is known that John Orloff and Kirk Saduski from Tom Hanks’ production company, Playtone, paid a research visit to the museum in Feb 2017. It is believed that Hanks himself visited one time, signing the Visitors Book “Woody”. Donald Miller regularly brings battlefield tour groups to Thorpe Abbotts.

** The 100th Bomb Group Association was originally formed by the World War II veterans themselves (at one time, the Association also maintained a spouses/family group called the 100th Bomb Group Auxiliary). It was later transformed into today’s 100th Bomb Group Foundation (link below) – a non profit group tasked with preserving and disseminating the first-hand historical accounts of the men, missions and machines that fought in the skies over Europe during World War II.

*** The Eighth Air Force was sub-divided into three ‘Air Divisions’, each with ‘Combat Wings’ usually comprising three ‘Bomb Groups’. So, the 100th Bomb Group flew with the 95th Bomb Group (Horham) and the 390th Bomb Group (Framlingham) as the 13th Combat Wing of the 3rd Air Division (LeMay’s) of the Eighth Air Force.

**** Finally, after endless delays, there is a broadcast date…. Fri 26 Jan 2024.

The National WW2 Museum in New Orleans has a really good article on its website looking at the history and unenviable reputation of the Bloody 100th Bomb Group. (BTW, technically it’s a “Bombardment Group”, but of course that gets shortened to “Bomb Group”, which in turn gets shortened to”BG”.)

¹ https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1391732

² Masters of the Air – Donald L. Miller

³ https://rafbeaulieu.co.uk/raf-beaulieu-control-tower-watch-office/ & https://390th.org/anatomy-of-station-153-the-control-tower/

Declaration: I was in the neighbourhood and just turned up.

Factbox

Website:

100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum

If you want to know more about the ‘Bloody 100th’ the 100th Bomb Group Foundation website has a huge database and is packed with detailed information on the air crews, ground crews, aircraft and missions.

Getting there: 100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum – Thor[e Abbotts

Common Road

Dickleburgh

Diss

Norfolk

IP21 4PH

It’s out in the countryside, so having a car is the easiest way to get there and there’s a free car park on site.

That said, it’s only a 10 minute car journey from Diss station, so you could go by train and then take a taxi.

Entry Price:

FREE. As a memorial they don’t charge to visit, but they very much appreciate it if you buy stuff from the shop, have a meal in the cafe, and/or leave a donation in the collection box!

Opening Hours:

- Open weekends from March to end of October 10am-5pm.

- Additional opening Wednesdays 10am-5pm May through September.

- Also open bank holidays.

- Last admission 4pm.

Where was 13th reconnaissance squadron located

Hi. I’m not sure, but I don’t think they were at Thorpe Abbotts at any time. A quick search suggests possibly RAF Mount Farm in Oxfordshire.

I spent a good day here on Saturday. Lovely memorial to the 100th. Some lovely displays and exhibits.

“The Sad Sack” was a cartoon strip by American cartoonist George Baker, that showed an inept, bumbling private and published in Yank: The American newspaper.

Service personnel couldn’t get used to the local pubs and the quaintness, often rowdy. In an effort to improve Anglo-American relations British pubs were made ‘off limits’ so servicemen took it upon themselves to obtain several barrels of the local brew and set up their own hostelry on site, usually in an old tool shed. The 100th at Thorpe Abbotts names theirs after the comic.

It’s a good museum isn’t it? 🙂

Thanks for your insights, Stephen.

Many of the old bases in Norfolk have memorials remembering the history of their own bomb groups. Check out http://www.hardwickfilm.com to see the documentary on the 93rd Bomb Group!

Yes, there are some really interesting memorials and memorial museums in that part of the world. I’ve seen a number of them, but not Hardwick yet. 🙂