The Dunkirk Maritime and Port Museum (Musée Maritime & Portuaire de Dunkerque) tells the history of France’s third largest port, its workers, its ships, and its seamen.

“Wait! What? Third largest?”

That may come as a surprise to some, because to most people, especially anglophiles, Dunkerque or “Dunkirk” is pretty much known for just one thing; the evacuation of troops from the beaches in Operation Dynamo May-June 1940: “I thought Dunkirk was just a wide beach and a mole!”

Nope! It is a huge port, located right at the most concentrated part of the world’s busiest shipping route (the English Channel/La Manche). In 2019 it handled 53.6 million tonnes* of goods and material, making it the third largest French port after Le Havre and Marseilles.

The Maritime & Port Museum

The museum itself, spread over three floors, occupies a former 17th century tobacco warehouse on the quayside at the old port.

Starting on the ground floor and working your way up, the displays and artifacts, including many excellent ship models, illustrate how the port started as a fishing village in a cove on the River Vliet estuary in the 8th century, and then began to grow.

History of the Port of Dunkirk

The port’s history is made complicated by its location in the coastal lowlands of Europe. At various times it came under the control of local fiefdoms who in turn owed allegiance to the major powers. When Dunkirk was not Dutch, or Flemish, or Spanish, or English, it was French. Which of course, is where it eventually remained.

From the 10th century through to 1646 the city of Duyn Kerke (Flemish: “church in the dunes”) was ruled by the Counts of Flanders who owed their allegiance to the Kings of Spain and the Austrians. By this time the port had a channel from the sea formed by two 350m jetties, and a large quay (almost half a kilometre), and its seamen were branching out into a new “industry”: privateering (authorised piracy), attacking English, Norman, and French vessels.

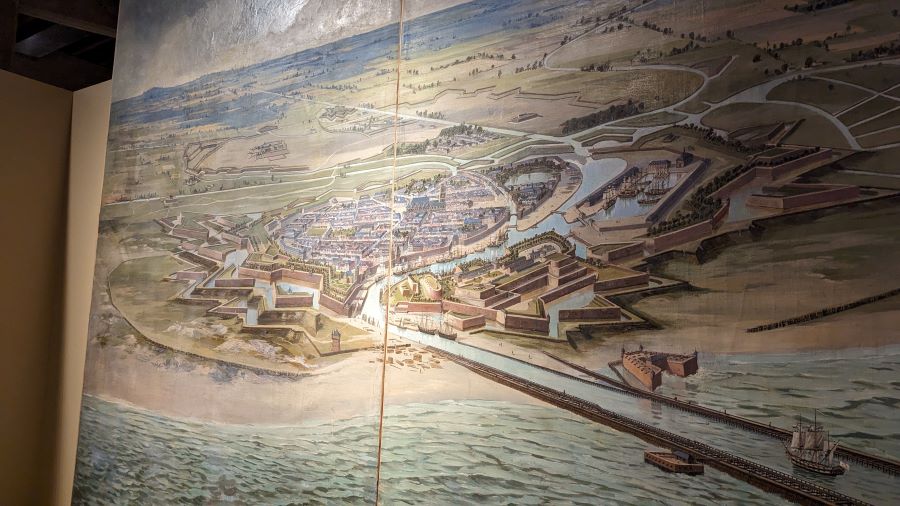

This spell of privateering was short-lived because in 1658 the English and the French teamed up as allies and captured Dunkirk. This changed everything for the port. Initially the English under Charles II were in charge, but they sold it to Louis XIV in 1662 and he immediately began improvements under the direction of ‘Mr Fortification’ himself, the Marquis of Vauban, France’s most talented military engineer.

Vauban began by extending the jetties and channel a further 850m out to sea. Then draining the wetlands behind the dunes, he built quays and massive fortifications in his signature star-shapes.

When Vauban began work on the port, Louis XIV granted Dunkirk ‘Free Port’ status, international trade took off and Dunkirk’s primary industry shifted from fishing to commerce.

Fishing had remained its primary industry up until the 17th century; particularly for cod and herring in the waters around Iceland.

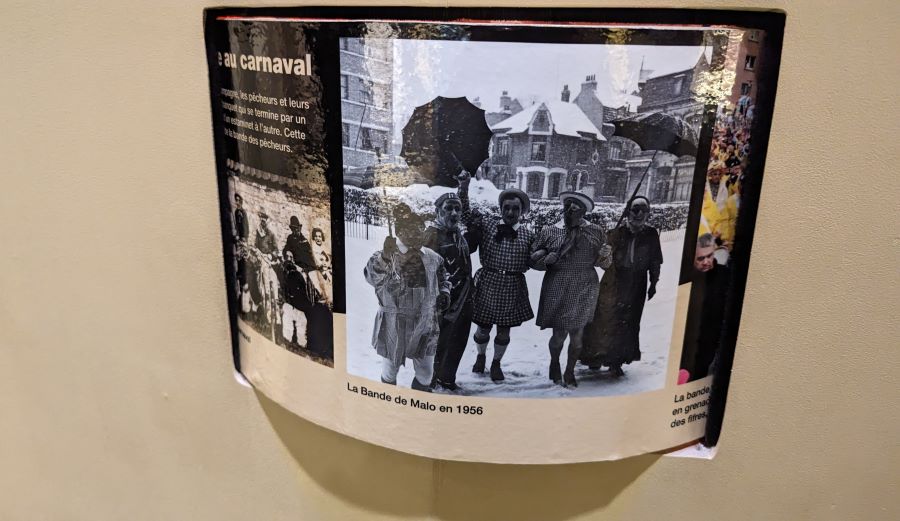

And it is still very much a part of the port’s cultural identity, expressed each year in the Dunkirk Festival which dates from at least 1676 and features colourful cross-dressing and the throwing of herrings (in vacuum-packaging) to the crowds from the balcony of the town hall!

The other thing Vauban did, was to encourage privateering again, particularly against the English and the Dutch. It gave birth to a local hero, Jean Beart, who was to the French as famous as Drake was to the English.

The English were greatly irritated by the capture of so many ships (a little hypocritical, given Drake’s actions against the Spanish a century earlier!) and perhaps that’s the reason that when the power base had shifted during the War of Spanish Succession they were able to force Louis, through the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), to demolish the port.

Work on rebuilding it started again under the reign of Louis XV. Works were undertaken to restore and repair the quays and docks, and the port blossomed once again with new industries being created such as glass, pottery and cloth manufacturing. A new lock was built in 1757, and Dunkirk even acquired a stock exchange. However, at the end of the Seven Years War (1763) the English returned to smash everything up again, and the port fell into further decline with the coming of the French Revolution at the end of the century.

The shifting politics of the region over the centuries proved even more complex than the shifting sands off the coast. Thankfully, the museum refers to them but it doesn’t spend too much time attempting to explain them!

Things get more positive in the 19th century, aided in particular by the arrival of the railway in 1848, and the latter part of the century saw major investment in quays, locks, and dry docks for ship repair.

All this required a large workforce to operate the port facilities and to load & unload ships. So, to maximise efficiency, the port also invested in equipment for handling the loads.

At its peak in 1900 over 4,000 dockers were employed at the port, and a large manual workforce was still required right up to the 1970s when containers took over.

Now, the port has extended even further. Up on the third floor of the museum there is another large map of the port and aerial view…

The port is now spread over 17 kilometres of coastline with another huge port basin at Mardyck near Gravelines. This is where the Dover-Dunkirk ferry terminal is located.

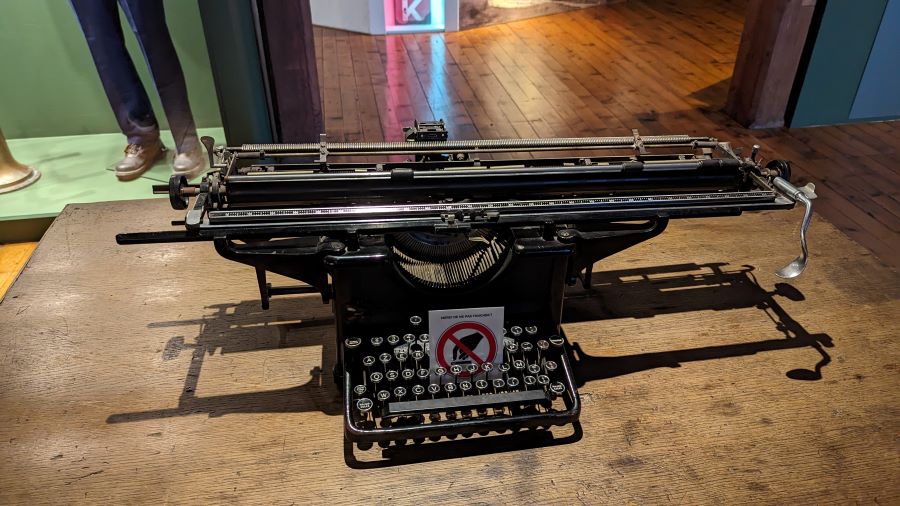

The third floor also has my favourite exhibit; a manual typewriter with an over-sized carriage, designed specifically to type up ships’ manifests.

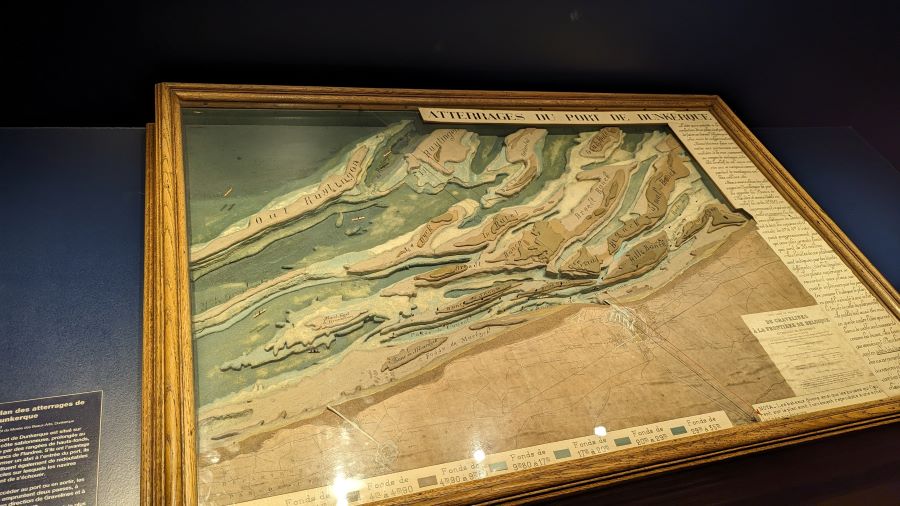

Sea Lanes and Sandbanks

The coast in this region is dominated by a network of sandbanks aligned along the shore.

This has always had advantages and disadvantages. In the early years it provided Dunkirk with extra defences. For enemies, it was difficult to reach the port without local knowledge. But for locals and friends it made safe navigation difficult, particularly in fog or at night. So life at the port of Dunkirk is, and has been, all about navigational marks, dredgers and lightships.

The dredger Pas-de-Calais II was built in 1939 originally for the port of Boulogne, but worked in and around Dunkirk for many years. Her 49 buckets could lift 600 m³ per hour of material from a depth of 23 metres.

The Museum’s Ships and Lighthouse

The museum’s collection also includes four museum ships moored alongside, and a historic lighthouse nearby.

The museum’s ships are:

- Entreprenant, a small harbour tug

- Guilde, a 1929 commercial barge

- Sandettié a lightship.

- Duchesse Anne 3-mast square-rigged sail training ship.

The Entreprenant was built in 1965 by local shipyard Ziegler Frères, to be a Dunkirk port tug. She worked for 40 years before being decommissioned and given to the Port Museum.

The Guilde was a commercial barge that carried mostly coal and sand on the inland broad gauge (‘Freycinet’ See Arques boat Lift) canals. Originally she was not motorised. Instead she was pulled from the towpath by a tractor.

The bright red Sandettié lightship rather stands out on the quayside, but that was her job. She was permanently moored, with her powerful lantern, foghorn and bright red hull, from 1949 to 1989 to mark the sandbanks off Dunkirk. Actually, her real name is Bateau Feu 6 (BF6) and her first location was on the Dyck sandbank. Her hull name was changed to Sandettié when she was reassigned to the Sandettié sandbank. While on station she had a crew of eight men whose job it was to keep her in good working order, to take and report weather data, and to monitor passing ships.

Duchesse Anne looks like a former 19th century square-rigged cargo ship, but in fact she was built in 1901 as a dedicated training ship, the Grossherzogin Elisabeth, to train officers and sailors for the German merchant navy. For three decades, she sailed around the Baltic Sea and off the coasts of Africa and South America with between 130 to 200 cadets on board and a crew of 15 to 20 officers. She was purchased by the city of Dunkirk in 1981, and is now the largest sailing ship in France.

You can visit these ships, or take guided tours of them… but only on certain days/times, and in the case of Duchesse Anne, not at all. She was closed for renovations in the spring and moved to a local shipyard in July this year (2024). She is not expected back till 2025 in time for the Dunkirk leg of the Tall Ships Race.

The Risban Lighthouse

(Photo: Alain.Darles, CC BY-SA-3.0)

The “Dunkirk Lighthouse” was built in 1842 on the ruins of Fort Risban (part of the fortifications built by Vauban at the end of the 17th century) out on the peninsula now formed between the old port and the Canal de Bourbourg. It’s almost 2 kms (4 mins) by road from the museum. Due to the quirky geographic layout of Dunkirk and the proximity of the border with Belgium, it can claim to be the most northern lighthouse in France, outshining the historic Feu de St Pol lighthouse (1938) which lies at the tip of the most seaward breakwater.

It is over 66 metres tall and to reach the light, you have to climb 276 steps. Its powerful lantern has a range of just over 50 km. The lighthouse was automated in 1985 and was listed as a historic monument in 2011, after which it was developed as a visitor attraction with a reception and an exhibition area focused on the history of the Dunkirk lighthouse, maritime signalling, navigational beacons and the men/organisations responsible for it.

* Traffic dropped to 49m tonnes last year (2023), but it is still the third largest in France.

Declaration: I was on a self-driving research trip supported by Pas-de-Calais Tourisme. Museum entry was complementary.

Factbox

Website:

Musée Maritime et Portuaire

The English language version of the website is next to useless. To get any detail, especially on visiting, it’s better to translate the French pages.

Getting there:

Musée Maritime & Portuaire de Dunkerque

9 Quai de la Citadelle

59140 Dunkerque

France

The port of Dunkirk can be pretty confusing to navigate. Sat Nav will certainly help! There’s no dedicated parking for the museum and the quay can get quite busy at times, particularly around lunchtime, so it can be hard to find a parking slot. Perseverence is the key!

Entry Price (2024):

| Museum | Museum + Ships | Lighthouse *** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | € 8.50 | € 15.00 | € 6.00 |

| Reduced rate* | € 6.50 | € 11.50 | € 4.50 |

| Family** | € 22.50 | € 39.00 | € 16.00 |

| Children under 7 FREE | |||

* Reduced rates:

- Groups on self-guided tours from 12 people

- Visitors aged 65 and over

- Young people aged 7 to 25 inclusive

- People with disabilities + accompanying person (1 per person)

** Family package: minimum of 4 people including 1 or 2 adults and up to 5 children and/or young people under 26 years old

*** Payment by credit card or cash, on site at the Risban lighthouse.

Be wary on ticketing. A significant number of TripAdvisor and Google Map reviews express disappointment that some or all of the ships they wanted to visit, were closed on the day or time of their visit.

Opening Hours (2024):

The Museum…

Open Monday to Sunday (closed Tuesdays except during school holidays) from 10.00 – 12.30 and 13.30 – 18.00.

The Ships…

| During School Holidays | Outside School Holidays | |

| Entreprenant tug | Open every day 14:00-17.00 30 min guided tours by reservation, subject to availability. |

Closed |

| Sandettié lightship | Open every day, 14.00-17.00 | Open every Sat & Sun, 14.00-17.00 |

| Guilde barge | Open on Saturdays, 10.00-12.30 | Open every Sat & Sun, 14.00-17.00 |

| Duchesse Anne | Closed for restoration till summer 2025 | |

The Risban Lighthouse…

Open every Sunday, 10.00 – 12.30

In case of adverse weather conditions (strong gusts of wind) the lighthouse may stay closed for safety reasons.