The London Museum Docklands opened its new exhibition ‘Secrets of the Thames: mudlarking London’s lost treasures’ last week.

It’s an exquisite exhibition focused on fascinating archaeological objects found on the Thames foreshore and the role of the “mudlarks” who found them and continue to expose thousands of years of human history with every turn of the tide.

People have been scavenging objects found in the mud on the banks of the river for centuries, and some could make a decent living from selling bits of copper & iron, rope & coal. Reports in the 19th century even suggest that some mudlarkers could make as much as £2,500 per annum. That’s £200,000 in today’s money – and I bet they weren’t paying tax! Nowadays, mudlarking is a popular hobby for history lovers, who have to be licensed by the Port of London Authority (PLA), and declare all their finds.

So, what have they been digging out of the mud and debris on the foreshore?

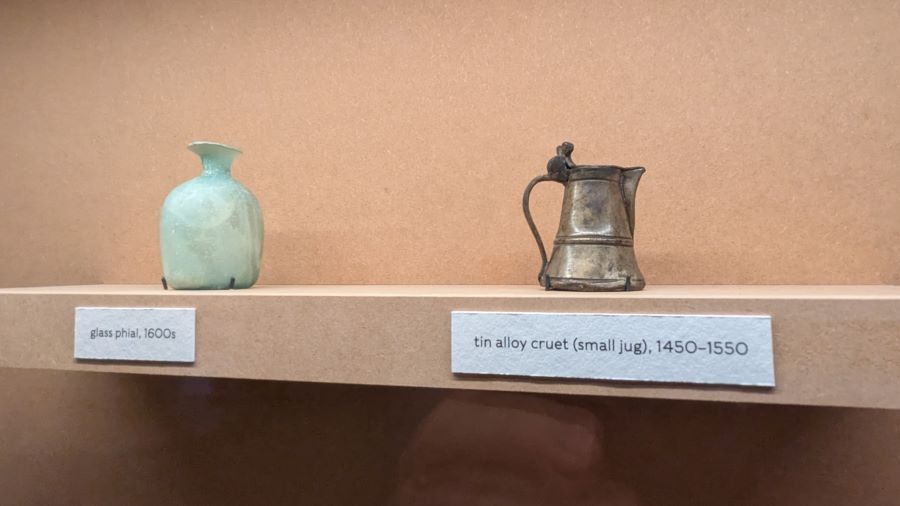

Well, lots of personal items have been dropped in the river over the centuries, including: chinaware, cutlery, clothing accessories, clay pipes, 18th century false teeth, medieval spectacles, 16th century wig curlers, rings and bits of jewellery.

Being a port, there are often marine artefacts among the mudlarks’ finds. This display case has some special items, like the small wooden pocket sundial, missing its gnomon (pointer). Amazingly, the top and bottom were found separately.

For me, the bosun’s whistle is captivating. Imagine the horror on the face of the bosun who accidently dropped this precious symbol of his rank in the river!

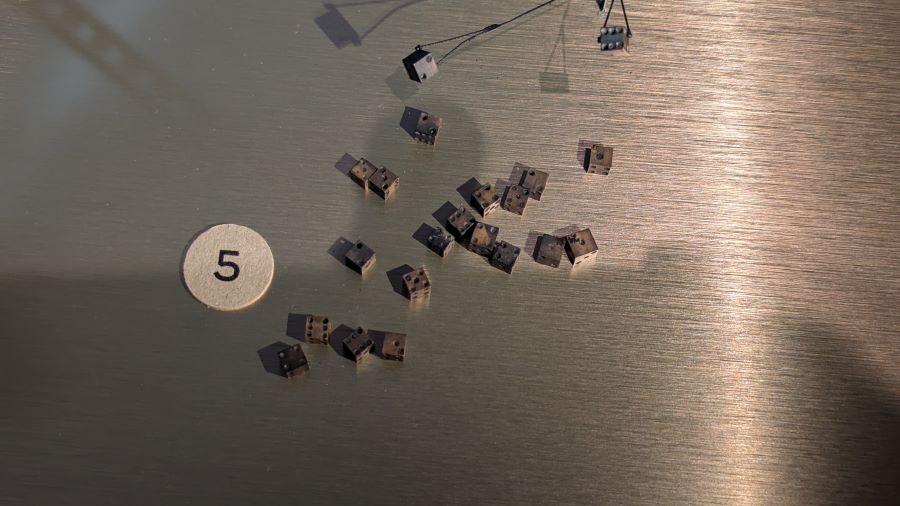

One intriguing find is a set of 24 tiny dice, less than a centimetre square, made of bone, and dating from the late 15th century. Clearly these belonged to an unscrupulous owner. When x-rayed it was revealed they were ‘loaded’ – weighted with mercury to bias which side they landed on. And to improve the odds even further, the numbers on some are repeated!

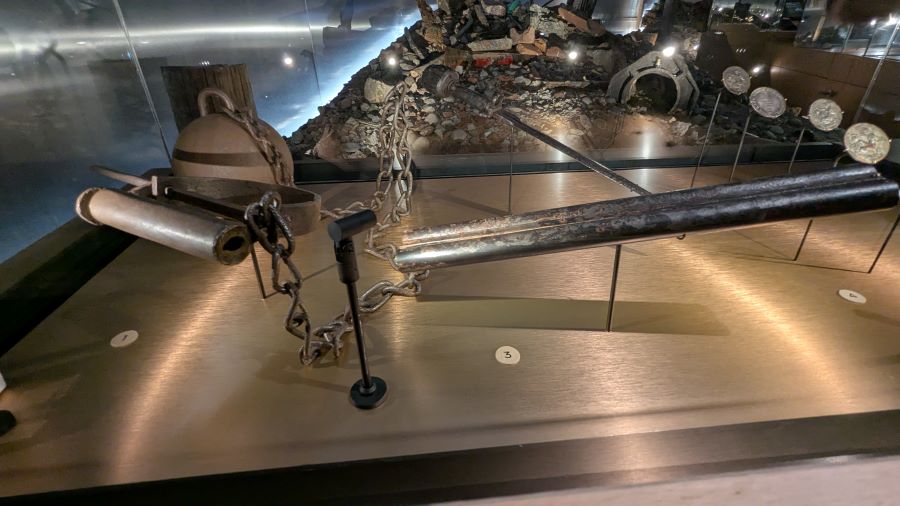

Speaking of ‘crims’, there are quite a few murky items dropped in the Thames. One display case has a few examples: a ball & chain, a sawn-off shotgun barrel, a dagger, and an interesting collection of Wimbledon medals stolen from American tennis champion, Peter Fleming, and recovered by a mudlark.

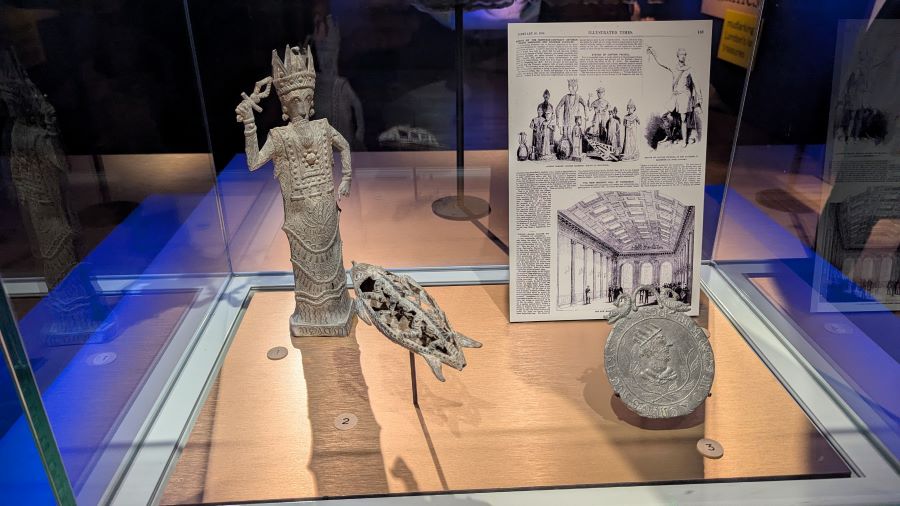

Some finds are not quite what they seem to be. Back in the mid-19th century two mudlarks, Billy Smith and Charley Eaton, found and sold items they uncovered… but not as frequently as they would like. So they decided to improve their prospects by manufacturing their own objects. They carved moulds and cast lead and brass objects, particularly of the kind of pilgrim souvenirs that were being found in the Thames back then. To make them look authentic, they used acid and Thames mud to tarnish them.

Between 1856 – 1870 they made thousands of these fake antiquities and sold them to dealers and the public who were hungry for these historical artefacts. After a while people became suspicious – surely somebody noticed that their ‘find’ rate was a little abnormal for mudlarks! – and they were exposed. Somehow, despite appearing in court more than once, they were never convicted, and today some of their counterfeit antiquities are worth more than the original might be.

For many, mudlarking is a passion and a way of life. Mudlarkers’ lives are dominated by the tides, which come and go twice a day but also fluctuate on a lunar-monthly cycle, between neap tides (smallest range) and spring tides (biggest range), which offer the largest exposure of foreshore. LAT tides (Lowest Astronomical Tide) occur rarely and are a bonanza for mudlarks!

And weather plays a part too; a period of low rainfall, or a strong westerly wind pushing water out into the estuary, can increase the amount of riverbank exposed upstream. All of this hydraulic activity – the tides and the river flow – churns the bottom up and provides a continuous stream of newly exposed objects.

The museum has created sections of simulated foreshore in the exhibition where visitors can search for objects. They can’t keep them though.

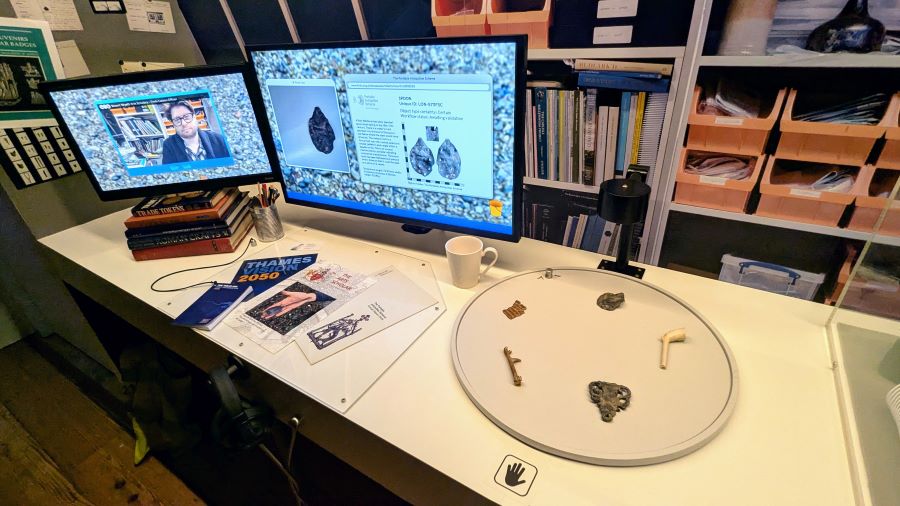

Once found, mudlarkers are obliged to report their objects through the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS). A Finds Liaison Officer will then research the object and decide its future; whether it is to be held in a museum collection, or whether the mudlark can retain it or sell it. There’s a good exhibit in the exhibition which demonstrates this process with examples of a PAS form, and a circular sample table which you can turn. When an object comes under the recording camera, the details are shown on a screen and a research officer describes what it is.

On average, the Portable Antiquities Scheme London Museum Finds Liaison Officer records around 700 finds per year and identifies around 5,000, with a small number acquired into the museum’s collection.

London Museum curator, Kate Sumnall, has been explaining to me the purpose behind the exhibition and the role of the mudlarks (Press Play)…

Not all the exhibits were found by Mudlarks.

The amazing Battersea Shield and Waterloo Helmet are real treasures.

The iron age Battersea Shield (350-50 BCE) was dredged from the bed of the River Thames at Battersea in London in 1857. It’s actually the bronze facia for a wooden shield. I believe this is actually a replica, with the original being held by the British Museum.

Similarly, the Waterloo Helmet, a pre-Roman Celtic bronze ceremonial horned helmet (150–50 BC), was dredged up near Waterloo Bridge in 1868.

In fact the 19th century was a busy period for archaeologists on the Thames. The widescale construction of bridges and riverside walls led to many objects being dredged up, including a rather splendid head from a bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (feature image above). The one displayed in the exhibition is a replica. Again, the real thing is in the British Museum.

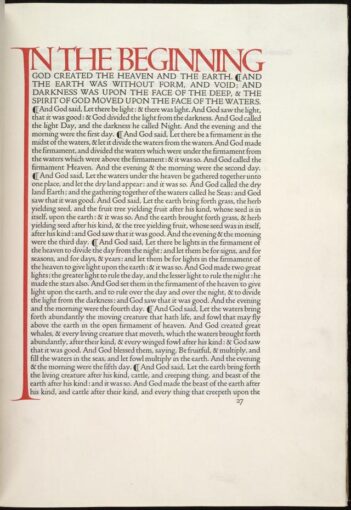

In some ways, the most interesting of the non-mudlarked finds, is the Doves Type, behind which there is a wonderfully human tale.

In 1900 Hammersmith-based Doves Press became a publishing partnership between the founder, T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, and his business partner Emery Walker. Unfortunately – although it had one big success, the 5-volume Doves Bible, hand printed and bound between 1902 – 1904 – the partnership wasn’t to last long. In 1908 it was dissolved and the assets divided. Included in those assets was the press’s own typeface, Doves Type, which had been hand-crafted and was considered an elegantly simple typeface that was instrumental in the success of the Doves Bible.

Cobden-Sanderson continued printing, but the dispute over the type became bitter. The traditionalist craftsman, Cobden-Sanderson, was something of a Luddite, and he feared his precious type would fall into the hands of the new modern mechanised presses. The agreement was, that on his death, the type would become the property of Emery Walker.

Realising his moment of departure was not far away, something snapped, and in 1916 he began making nightly visits to Hammersmith Bridge where he surreptitiously “bequeathed” the metal moulds and punches (characters) to the Thames, thereby robbing Walker and the world of his beautiful type. The thing is… altogether, the type weighed over a metric tonne (1,000 kilos), so Cobden-Sanderson had to make around 170 night-time visits to the bridge!

(Photo: Public Domain)

A century later, interest in the Doves typeface had grown and at least two people set about digitally re-creating it, based on the books left behind. One of those, designer Robert Green, decided to go a step further and hired Port of London Authority divers to go look for it. Amazingly, they found several hundred of the punches, some of which are on display in the exhibition.

The Museum of London – Docklands ‘Secrets of the Thames: mudlarking London’s lost treasures’ exhibition runs to 01 March 2026. Kate Sumnall tells me that, rather like the ever changing landscape of the Thames, some artefacts in the exhibition will be changed every four weeks, to keep it refreshed.

Entry to the Museum is free, however the exhibition requires tickets starting at £16 for an adult.