The London Transport Museum has a huge collection of fascinating vehicles, artefacts, documents and memorabilia covering, not only the technical history of London’s growing transport networks from the 19th century and earlier, but also many of the social changes that developed alongside them.

The collection was started in the 1920s and first displayed in a bus garage in Clapham during the 1960s. A decade later it was moved to Syon Park near Twickenham, and in 1980 it moved to its current location in the former flower market in Covent Garden. A large part of the collection (320,000 objects) is also stored at the London Transport Museum Depot in Acton, which opens to the public on special visitor days.

The Grade II listed steel and glass museum building displays the vehicles and artefacts over three floors. If you wanted to tackle the museum in a chronological order, it’s probably best to head straight for the top floor where the earliest forms of public transport are displayed.

Early Public Transport History in London

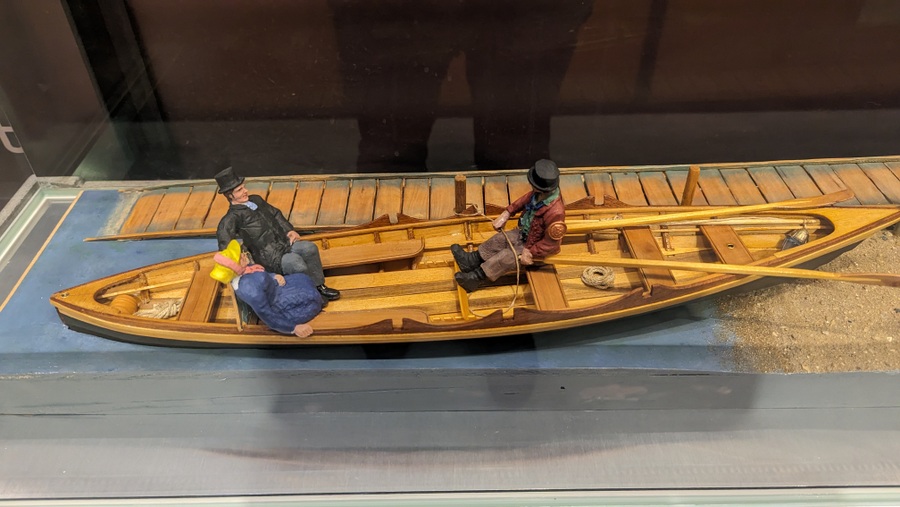

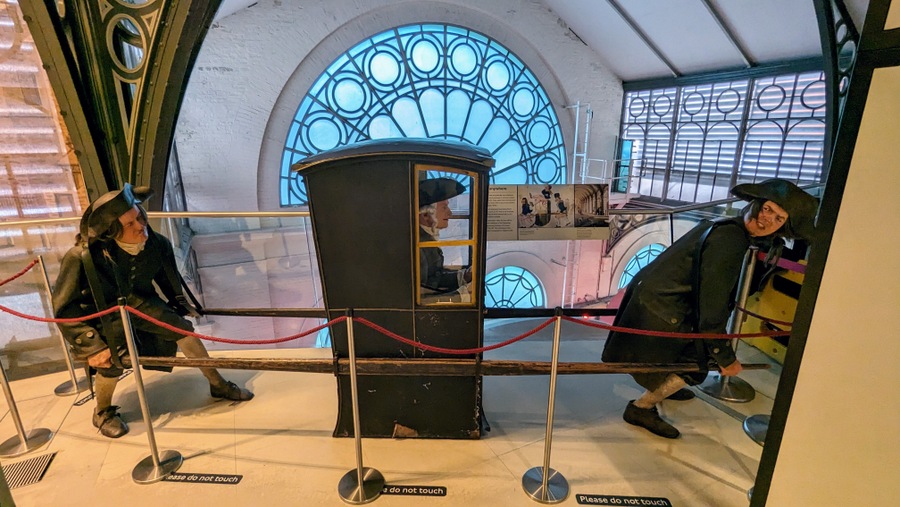

Before the 19th century, there really wasn’t any public transport in London, or any city for that matter. Since Roman times people made their way about on foot, on horseback, or by boat using the great thoroughfare, the Thames. But the Thames was both a roadway and a barrier. Until the mid-19th century there was only one bridge, London bridge*. If you were wealthy you could hire a boatman to ferry you across or along the river, or you could hire two strong men to carry you about for short distances in a sedan chair.

Most people, though, just walked. After all the city was quite small. A thirty minute walk from the centre and you would be in countryside.

Things began to change at the start of the 19th century with the introduction of horse-drawn Hackney Cabs (from the French word Haquenée – a horse for hire) who could be hired on the street. By 1805 there were 1,100 licensed hackney cab drivers carrying passengers around the city.

The only other form of public transport was the stage, which took pre-booked passengers on inter-town journeys. In 1825 there were around 600 stage coaches making daily journeys to nearby towns, in what, as London grew, would become the suburbs.

In 1829 a revolutionary new transport service came to London thanks to George Shillibeer who imported the idea (and the name) from Paris.

Shillibeer’s Omnibus was a horse-drawn carriage, operating a fixed route from Paddington, via Islington, to the Bank of England. It departed Paddington Green at 9.00am, 1200noon, 3.00pm, 6.00pm and 8.00pm and a similar schedule in the other direction with the last service departing the Bank at 10.00pm. Importantly, just like the hackney cabs, it could be hailed on the street. It was London’s first bus service.

The idea was so popular that a decade later there were 620 licensed omnibuses operating in London. Unfortunately for Mr Shillibeer the competition forced him out of business in 1834.

So, now the bus had been invented, what was next? The double-decker bus!

This is a replica of bus operator, Thomas Tilling’s 1875 ‘knifeboard’ bus, so called because the longitudinal bench on the top deck made it resemble a Victorian knife-cleaning board. Knifeboard buses were the first double-deckers. They first started appearing around the 1840s. This bus could carry 24 passengers, 10 inside, 14 on top.

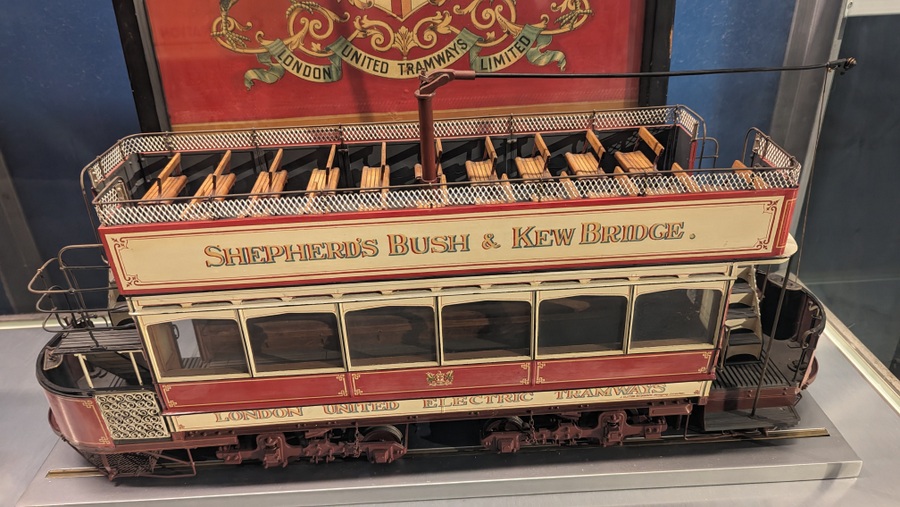

The next development in bus technology, was… trams. With less friction between wheels and tracks, trams were simply more efficient. It could mean using two horses instead of three or four.

John Stephenson’s company made advanced lightweight horse trams or ‘streetcars’ in New York and exported them all over the world. The London Tramways company took delivery of over 300 between 1879 and 1883. The museum’s Stephenson tram was operational till 1910. It was restored in the early 1990.

Overgound and Underground Railways in London

The 19th century was the age of railways, the first being the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in September 1830. Railway lines into London weren’t far behind. London’s first terminus, Euston Station, built for the London – Birmingham Railway, opened in 1837, but London’s first underground railway, indeed the first in the world, the Metropolitan Railway between Paddington and Farringdon, took a little longer. It didn’t open till 1863.

On the museum’s second floor, there is a magnificent Metropolitan Railway A-class steam engine from 1866.

Engine No. 23 is the only surviving locomotive from a batch of 66 built in Manchester for the Metropolitan Railway between 1864 and 1869. It spent most of its working life on the sub-surface lines, but when the Circle, Metropolitan and District lines began to be electrified around 1905, it spent much of its long working life (till 1948!) on the Met’s ambitious extensions. The Metropolitan Railway was keen to become a mainline railway and by 1899 had extended out as far as Rickmansworth and on to Brill in Buckinghamshire… a spot I know well, as years ago, family friends bought the Beeching-ed station remains and some of the surrounding fields, and used it as a summer camp. It’s nice to imagine Engine No. 23 huffing and puffing its way into that station, hauling the elegant wooden varnished coach to which it is still attached. Metropolitan Railway coach No. 400 was built for that line.

The Age of Steam

The age of steam changed everything from manufacturing to the pumping stations that fed clean water to Londoners and took away their waste. It revolutionised transport above and below ground, and on the waterways. When steamboats appeared on the Thames in 1815, people were suddenly able to travel into central London from as far as Gravesend, Margate and Ramsgate, with stops at Woolwich and Greenwich. River traffic peaked in the 1850s when the steamboats carried millions of passengers a year, and while most passengers were pleasure-trippers, some 15,000 passengers a day were a new phenomenon – commuters.

There was a downside. With so much traffic on the river there were inevitably collisions. This model is the Princess Anne, built in 1865. She carried pleasure trippers to the seaside resorts of Kent & Essex, but in 1878 a coal ship ran into her and 640 people died as she sank.

And there was a downside to steam locomotives too. As much as the early underground, or ‘partially underground’, railways tried to ventilate their track, and use condensers on their locos to reduce the steam, steam engines were never going to be the answer. Electrification was inevitable.

The Electric Age

Down on the ground floor of the museum, is an example of the early electric trains; a City & South London locomotive and carriage from 1890…

… and, back up on the second floor, alongside Engine No.23 and its carriage, is another Metropolitan Railway locomotive – a second-generation electric locomotive and carriage from 1922. Most of us would recognise this rather grand electric locomotive as a forerunner to the modern tube train.

Back down on the ground floor** is something that those of us of a certain age will definitely recognise. These 1938 stock carriages were eventually retired from service in 1988, six weeks short of 50 years service. This particular car travelled more than one million miles in its 40 years service on the Northern Line. As a student in London in the 1970s, I may even have travelled on it!

The Age of the London Bus

The step-change for horse-drawn buses and trams, came not with steam power in the 19th century, but with the internal combustion engine and electric motor at the start of the 20th century. And on the London Transport Museum’s ground floor you can see numerous glamorous examples of that transition.

It seems odd now, in these days of climate change and the need for sustainable energy, that electric trams and buses should have lost out to the petrol and diesel engine, but they did.

(sv1ambo CC-BY-2.0)

Electric tramways were all over London in the early 1900s. As the Great War broke out in 1914, there was a network of fourteen electric tramway systems in London – 11 of them run by local councils, three by private companies – and they were carrying 600 million passengers a year.

The museum has an electric tramcar from 1910. No. 102, was one of six built for West Ham Corporation Tramways. It is an elegant Edwardian tramcar with its open-ended balcony and curved staircase, but in some ways the plainer K2 class electric trolleybus next to it, is more interesting. It’s amazing to think that at in 1939, at the start of World War II, we were using electric vehicles on the roads for public transport.

The trolleybus was a sort of hybrid vehicle; not on rails, so lacking the friction benefits, but more flexible in its ability to change route by switching between overhead power cables.

The problem was that they were literally outmanoeuvred by motorbuses, who could go anywhere. A tram on rails or a trolleybus following its power line catenary had nowhere to go if stuck behind a breakdown, accident, or traffic jam. A motorbus could drive around it.

The Age of the Motorbus

The London Transport Museum has some special buses, starting with perhaps its most popular exhibit, the colourful Leyland X2 type motorbus from 1908 (on the right) – why can’t TfL buses be that decorative today?!

Next to it, the not quite so colourful, gold-painted, RT type motorbus from 1954. Actually this became the standard post-war London bus, but it was first introduced in 1939. Its mass-production and deployment were delayed by the war. This one was painted gold to mark the Queen’s Golden Jubilee in 2002.

The red Routemaster bus is famous around the world and is a brand icon for London. This one operated from 1963 – 1985.

The double-decker B-type bus was London’s first successfully mass-produced bus when it first began operating in 1914, but it quickly got caught up in the war effort when over 1,000 of them were sent to the front in Europe.

That too was the fate of this B-type, LH-8186. One day it was happily ploughing its route – No.11, Barnes to Liverpool street – the next, it was off to France as a troop carrier! Hence the green paint.

The Age of the Internal Combustion Engine also moved the Hackney carriage on from its horse-drawn beginnings. By 1936 purpose-built and highly functional vehicles like the Austin Low-Loader taxi had started appearing. And there’s a modern day diesel black cab near the entrance to the museum’s ground floor.

London Transport Museum permanent and temporary displays and exhibitions

The London Transport Museum is not just about vehicles. There are plenty of London Transport artefacts on permanent or semi-permanent display, and a continuously changing series of temporary exhibitions, like the recent gallery of photos of Underground stations being used as bomb shelters.

Things to look out for…

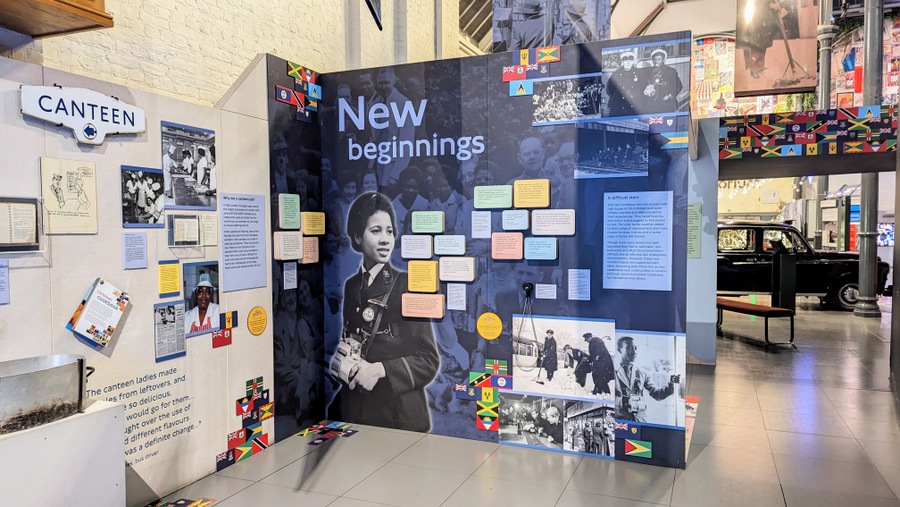

The display area on the ground floor dedicated to the London Transport staff, particularly those from different ethnic backgrounds who found jobs and careers with London Transport, now TfL. It’s a really interesting display with personal stories from immigrants who came to London in, for example, the Windrush generation, or the wave of Ugandan Asians. Look for the uniform embellishments made to accommodate Sikh and Rastafarian staff.

uniform

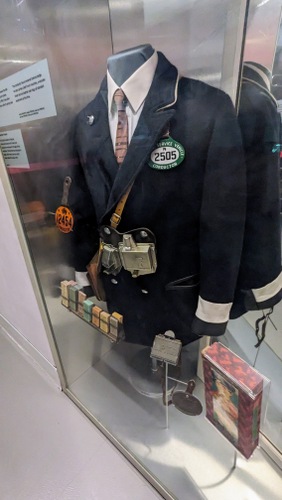

Uniform has always been important to London Transport and you’ll find examples and photos scattered around the museum. The reproduction of a 1939 Central Bus conductor’s uniform for example includes his ticket belt, cash bag, ticket punch, silver griffon buttons, white stripes on the sleeves (to made hand gestures more visible) and an official enamel badge with the conductor’s licence number.

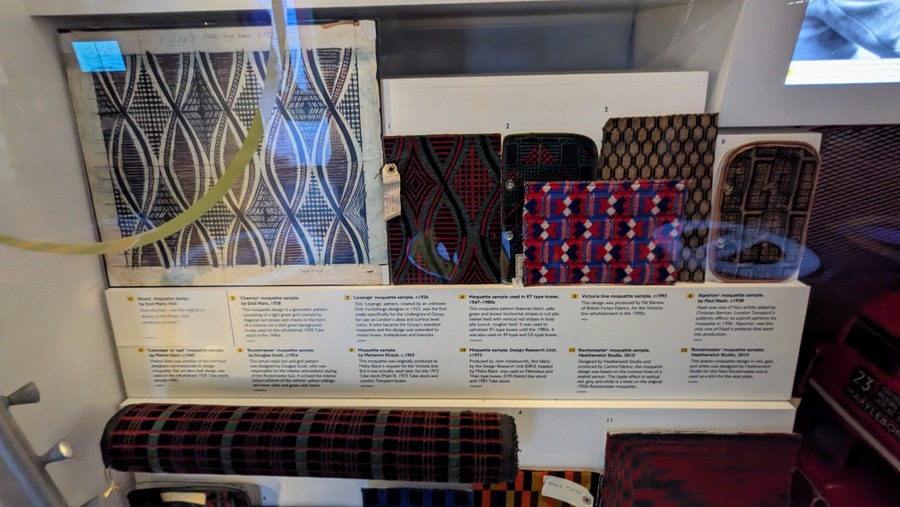

Have you ever given much thought to moquette? No? Thought not!

Moquette is the woven woollen patterned fabric*** used on seats and other furnishings since the 1920s. London Transport used to commission designers to come up with stylish patterns for tube trains, buses, and more recently the cable car over the Thames. There’s a display, taken from the Museum’s collection of 400 samples, showing the history of moquette designs over the years, and surprisingly, it’s not as dull as it sounds!

There’s a display about ticketing systems and passenger flow. Not surprisingly, contactless tickets ensure a faster flow rate at the gates than the old manual card ticket reader, but TfL’s view of future ticketing systems, which appears to use facial recognition, is a little worrying.

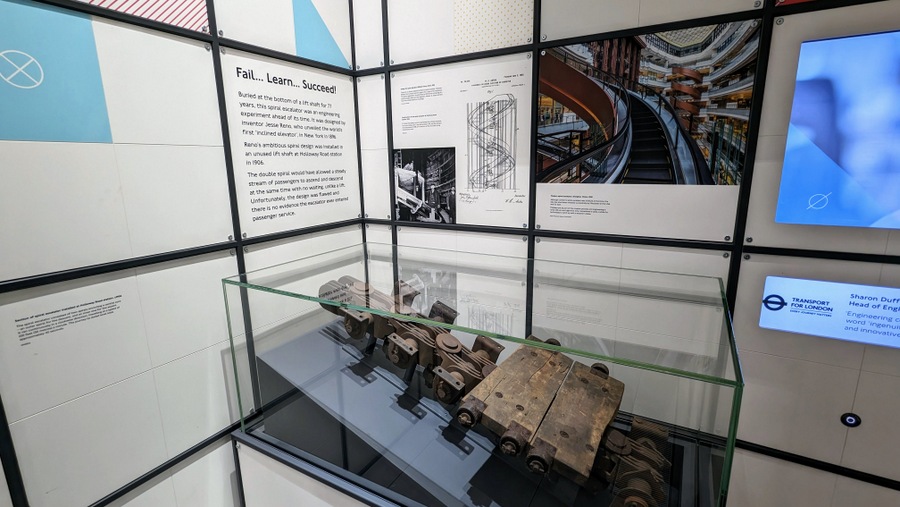

Now I think this (below) is just asking for trouble.

We all know how frequently escalators break down. Actually, they are amazingly reliable, but when they do break down or need refurbishing, they are usually out of action for months. We’re talking about straight line escalators here, but imagine how confident you would feel with a spiral escalator!

This bit of rusty old iron and wood is part of a spiral escalator installed in a lift shaft at Holloway station in 1906. It was highly ambitious, having an inner ascending spiral staircase and an outer descending spiral staircase. They were designed to run at 30.5 metres per minute (100ft), which would enable a passenger standing still to ascend to street level in 45 seconds.

Unfortunately it didn’t work, at least, not reliably, and was abandoned. But the concept wasn’t abandoned. The photo in the background is of a working spiral escalator in Shanghai, made by Mitsubishi.

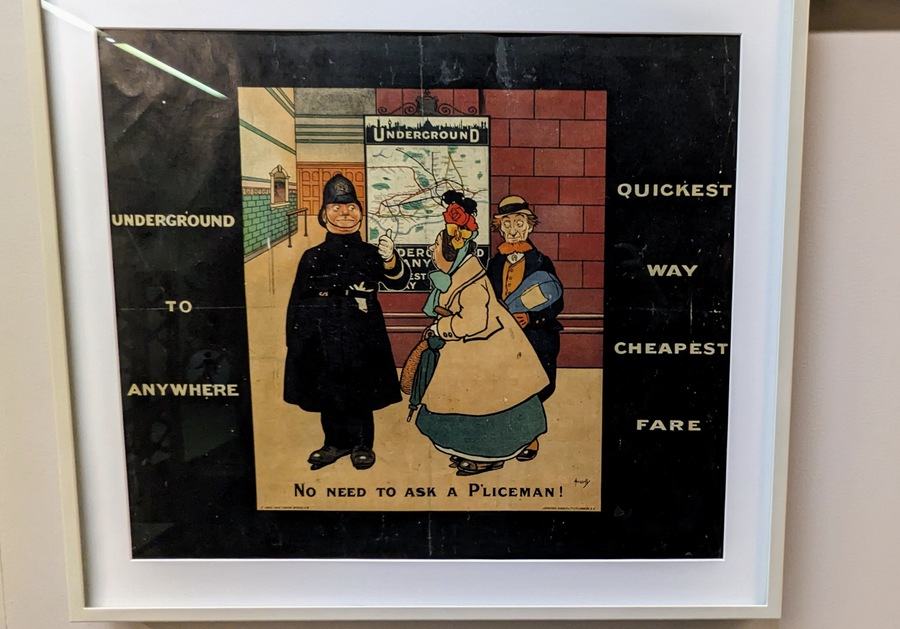

London Transport/TfL has always placed a lot of emphasis on design. There are displays of Tube station architectural design and signage for example, and their advertising posters are respected as artworks. The museum has permanent exhibition of over 100 posters taken from their collection of 30,000, dating from the early 20th century. The gallery runs over two floors.

Their earliest poster, ‘No need to ask a p’liceman’ by John Hassall in 1908 is displayed in the exhibition, and down on the ground floor.

And continuing that focus on design, this September the museum will be running a play in their theatre, about the life of Harry Beck, the designer of the world-famous diagrammatic tube map.

‘The truth about Harry Beck’ will run from 14th September to 10th November 2024.

* The next two bridges, Westminster and Blackfriars, weren’t built until 1750 and 1769 respectively.

** There is a sort of logic to the museum layout. It may be broadly chronological from top to bottom, but the trains on the second floor are both London Metropolitan Railways trains, albeit from different generations.

*** 85% wool x 15% nylon. Very tough, very durable.

Declaration: I was on a press visit to the museum. Entry was complementary.

Review rating (below) criteria

Factbox

Website:

London Transport Museum.

Getting there: London Transport Museum

Covent Garden Piazza

London WC2E 71313.

It’s easy to get to. The nearest Tube stations are Covent Garden or Leicester Square, then Charing Cross, Embankment, or Holborn. The nearest bus stops are Strand or Aldwych

Entry Price (Jul 2024):

The museum has a weird ticketing system. If you are 18 or over, you have to buy an Annual Pass and then you can book your timed entry ticket. Or you can think of it the other way around: you buy your ticket, (the price is not dissimilar to other London attractions) and get the added bonus of being able to return for free anytime in the next 12 months.

There are three types of Annual Pass:

Unlimited – Unlimited daytime entry to the Museum in Covent Garden for a whole year.

Off Peak Annual Pass – Entry to the Museum on weekdays after 2pm (term-time and summer holidays only for a discounted price).

Annual Pass Plus – Unlimited daytime entry to the Museum in Covent Garden plus free entry for you and two children at their Depot Open Days in Acton.

| Unlimited Annual Pass | Adult | £24.50 |

| Concession | £23.50 | |

| Local Resident | £18.50 | |

| Universal Credit/Pension | £1.00 | |

| Off-peak Annual Pass | Adult | £22.50 |

| Annual Pass + | Adult | £70.00 |

Opening Hours:

The museum is open daily from 10:00-18:00