The Musée des Arts et Métiers (Museum of Arts and Crafts) in Paris is almost the French equivalent of the Science Museum in London, and it is absolutely packed with the most fascinating historic, scientific, mechanical, experimental and industrial exhibits. Be prepared to allocate plenty of time for your visit!

The museum, created in 1794 and refurbished in 2000, displays 2,400 objects. They are just a small part of the national collection of 80,000 “new and useful inventions” which the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (CNAM) began gathering when it was established in 1704. It occupies two connected buildings on the CNAM campus: the 18th century Priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs and its church.

The main museum building is rectangular on three floors surrounding a courtyard. It has mostly long halls with big windows letting in natural light. Then, at ground level, it connects with the church which is also an exhibition space. The museum’s artefacts are split into seven categories…

- Scientific instruments

- Materials

- Energy

- Mechanics

- Construction

- Communication

- Transport

The recommended route through the museum is to start on the top floor (2nd) and work your way around and down.

2nd Floor – Scientific Instruments and the production of Materials.

The first two galleries have scientific instruments from the period between 1500-1750, and then the second covers the following period up to contemporary times.

In the 16th century, scientists and thinkers were trying to accurately measure the world and the heavens, and they made some exquisite instruments for this purpose. From simple wooden and brass quadrants and backstaffs to measure the angle of celestial bodies, to astrolabes to predict their movements and telescopes to observe them.

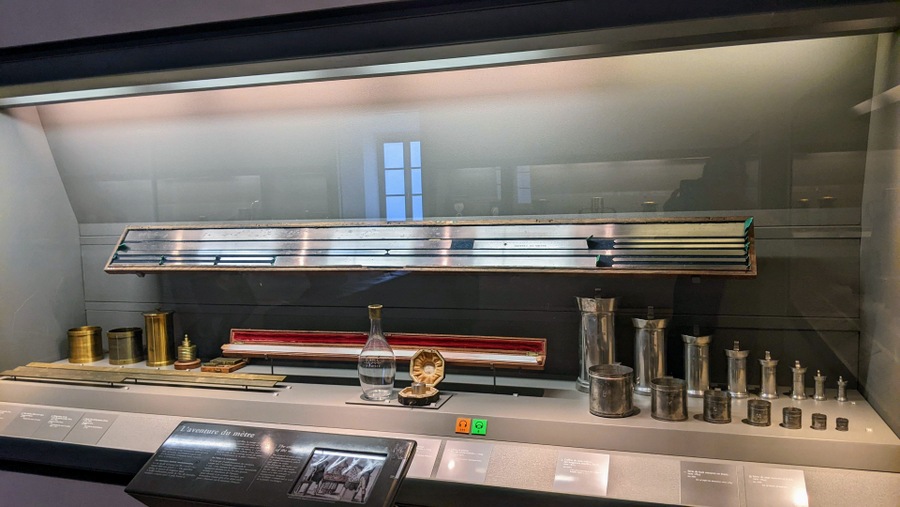

Then, back on Earth, there were the more mundane and commercially important things to measure – height, length, weight, volume, pressure, etc. And there had to be agreed standards for these things. The metre and the metric system were created in France in the 1790s, and with them came the kilogram and the cadil, the original name for the litre.

One of those involved in drawing up the metric system was Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier (1743 -1794), an aristocratic chemist recognised for his study of gases and elements, and being the first to recognise oxygen and hydrogen as elements. In fact he wrote the first proper list of elements. Unfortunately, despite his scientific achievements in those revolutionary days, he was accused of tax fraud and was guillotined. The museum has assembled some of his ‘gasometres’ from his laboratory.

Measuring time reliably was increasingly important in the late 18th century. In France, just as in England, the race was on to develop accurate chronographs that could keep track of time, and thus longitude, for naval and merchant mariners.

One of France’s most important clockmakers was Swiss-born Ferdinand Berthoud (1727 -1807). He became a master watchmaker in Paris in 1753 and, as ‘Horologist-Mechanic’ to the French Navy, was noted for his expertise in marine chronometers. There is a display of his workshop artefacts in the centre of the second Scientific Instruments gallery.

And then we move into the 20th century and a more familiar generation of scientific instruments such as a supercomputer, a cyclotron, an electron microscope and an extra-terrestrial rover.

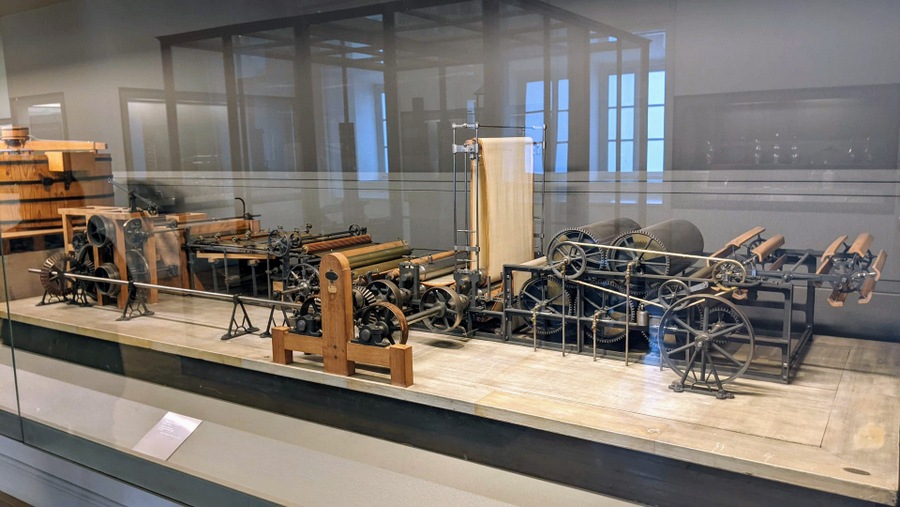

The last gallery on the top (2nd) floor, focuses on ‘materials’, namely fabric and paper manufacturing.

Highlights are, Jacques Vauxcanson’s extraordinary programmable loom for weaving patterns in silk or other fabrics, which he patented in 1748…

…and Louis-Nicolas Robert’s “machine for making paper in very long lengths” that he patented in 1799. The first continuous papermaking machine.

1st Floor – Construction, Communication, Energy and Mechanics.

The Construction gallery, and half-gallery on an upper level, has mostly models of construction techniques and machinery through the ages.

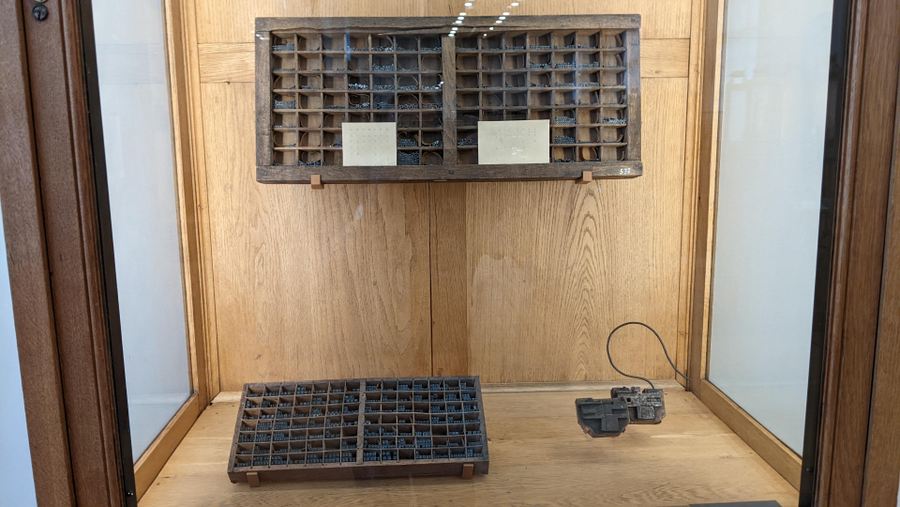

The Communication gallery has two halls and starts with the printed word from the 18th century; remember, CNAM was only established in 1704, so its artefacts date from then). Moveable wooden type (characters) were used for typography in China in the 10th century, but by the 15th century Europeans were casting types in metal.

In 1792, French inventor Claude Chappe demonstrated his design for a semaphore telegraph. Telegraph towers, with large vanes that look rather like a man waving his arms about, were set 5 to 15 kilometres apart. Armed with telescopes, the operatives at each tower could read the coded signal being waved from an adjacent tower and pass it on to the next tower. The vanes could create 98 different shapes, and the system was so successful that before long there were Chappe telegraphs on towers or tall buildings, all over France.

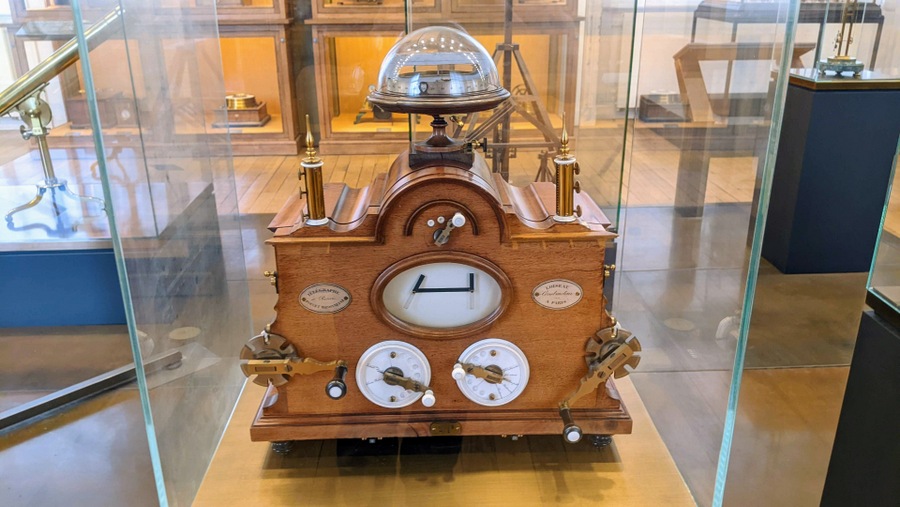

Then, in the new century (19th), came the electric telegraph. Now the nodal points were connected by wire, but instead of going down the route of Samuel Morse, transmitting simple dots and dashes turned into sound or light, the French telegraph machines re-created Chappe’s waving arms! It saved having to retrain thousands of Chappe semaphore operators.

Not all the electric telegraph machines used the Chappe system. This one, made in 1850 by Paul Gustave Froment, used a conventional alphabet.

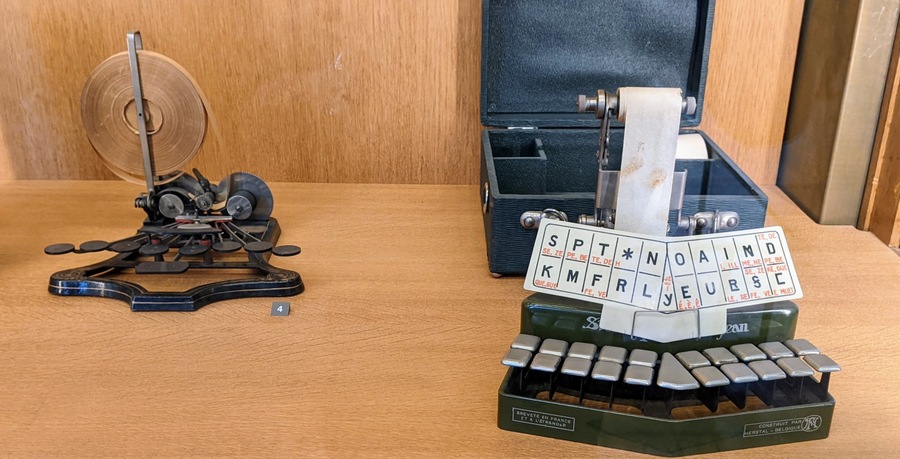

And keyboard machines were also developed to manually record transmissions or conversations.

Also in the 19th century, inventors were beginning to look at moving images…

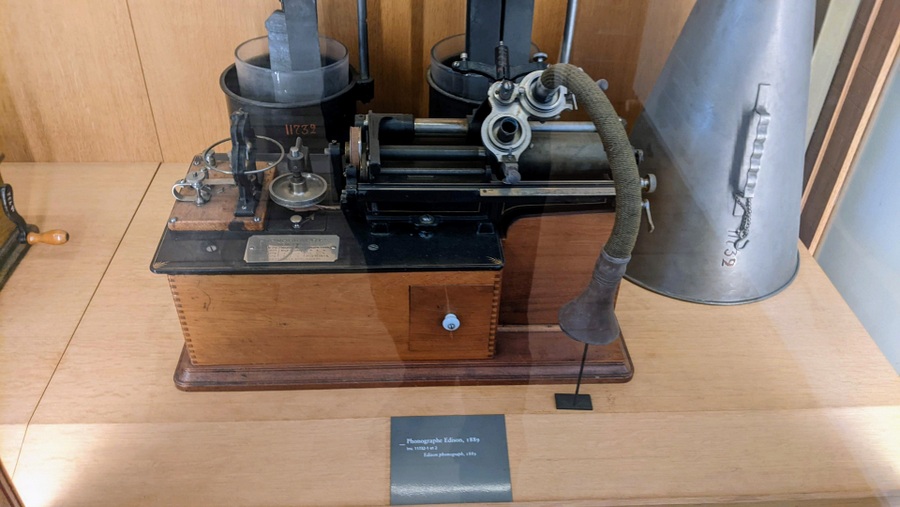

And moving into the second hall of the Communications gallery, we’re finding ways to reproduce sound and images. Starting with some of Gaumont’s gear for early cinematic performances.

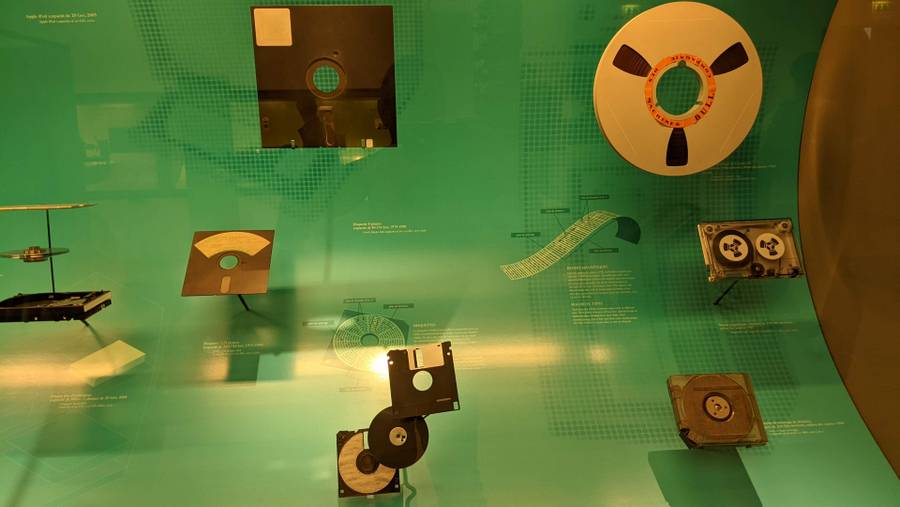

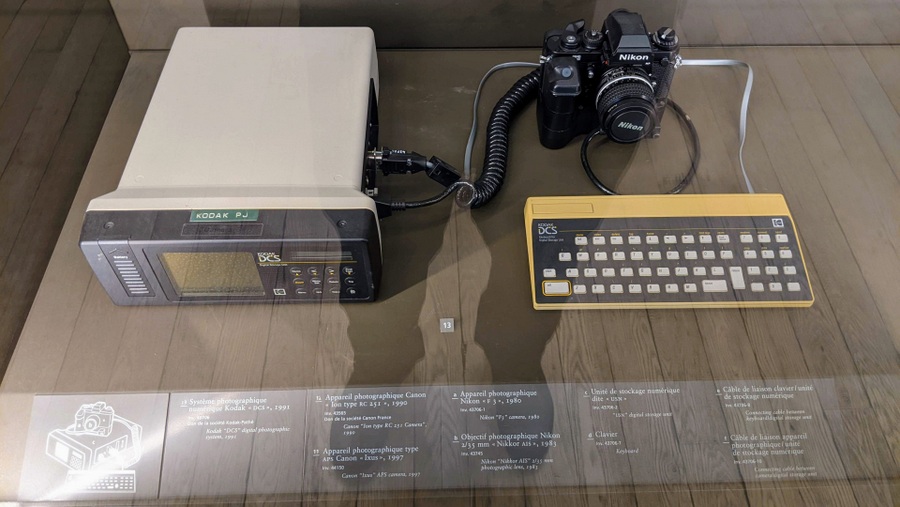

At the start of the 20th century Morse code was still very much with us, now with Marconi’s help, transmitted through the air (remember Titanic’s frantic radio operators in 1914), but the war years accelerated the development of radio and telephonic communication and by the end the century we had global televisual communications and the beginnings of digital communications.

The Energy gallery focuses on energy generating machines or motors mostly through models (rather like the Construction gallery) in this case of hydraulic, pneumatic, and steam machines.

Highlights to look out for include: the 1912 Rateau system steam turbine of the Haut-Katanga Mining Company; the 1844 water turbine (rather more sophisticated than the 14th century Cougnaguet mill turbines); the 1861 Lenoir gas engine; and the 1895 De Dion motor, one of the first gasoline engines.

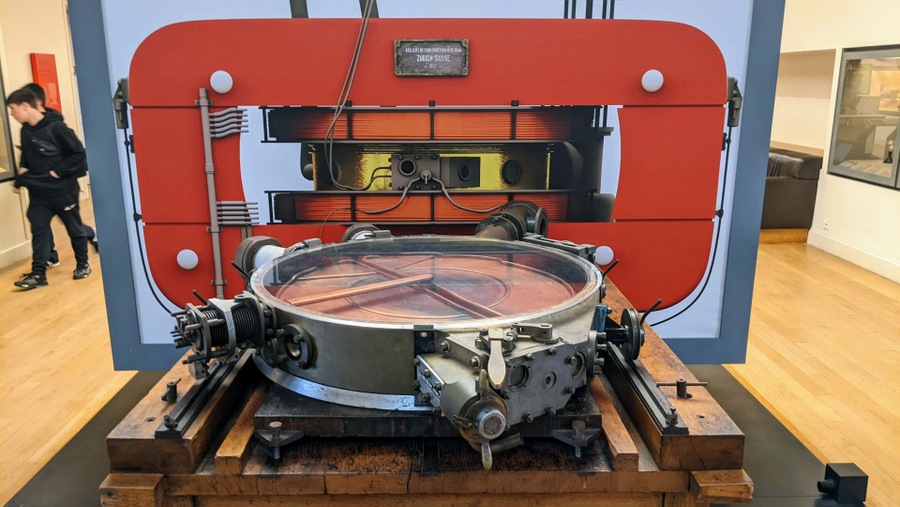

The Energy gallery gives way to the Mechanics gallery which has some amazing machines and models.

It’s not hard to get totally engrossed in some of the beautifully engineered mechanics on display in this room, especially some of the animated examples of clever movements and gearing.

It’s not hard to get totally engrossed in some of the beautifully engineered mechanics on display in this room, especially some of the animated examples of clever movements and gearing.

It’s also not hard to admire the amazing machine tools used to make them.

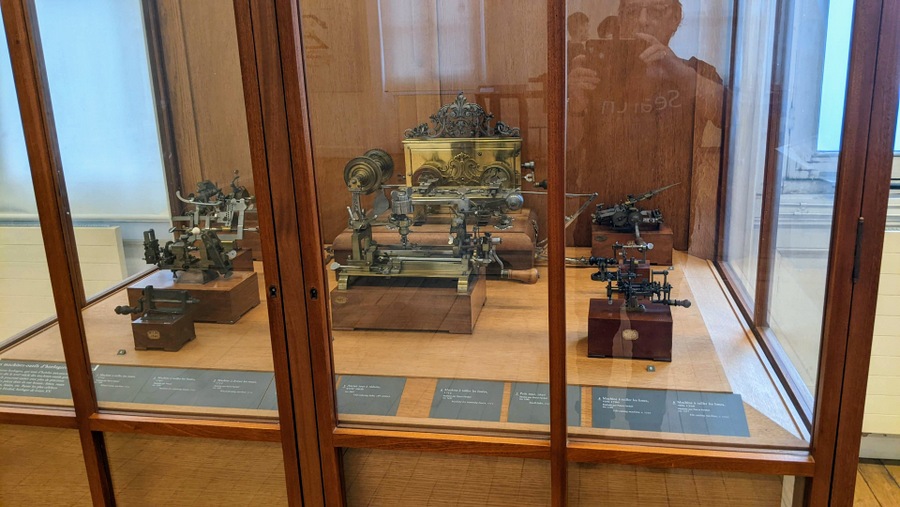

These include tiny precision machine tools made by watchmakers from as early as the 16th century to help them make the parts they need. Craftsmen like Pierre Fardoil, watchmaker to Louis XV, made tools to stamp out wheels, grind out the teeth for gears, and make springs on a tiny scale.

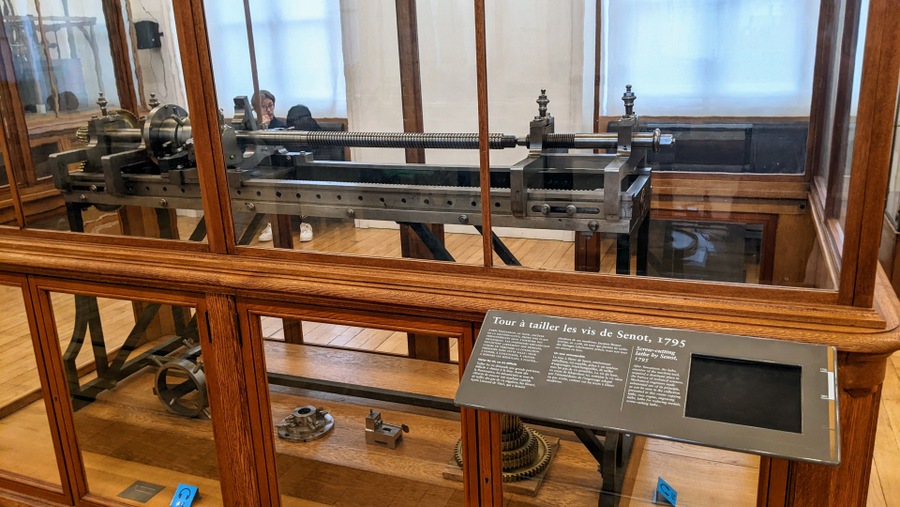

Other engineers were making larger machine tools for shaping, drilling, routing, bevelling, grinding, and cutting screw threads – a particularly difficult process that has occupied the minds of engineers like Leonardo da Vinci since medieval times. In 1568, Jacques Besson invented a reasonably precise screw-cutting (threading) machine based on Leonardo’s designs, but it wasn’t until 1795 that François Senot nailed it (sic) with his screw-cutting lathe.

The Stairwell

At the end of the Mechanics gallery, the hall opens out to a magnificent stairwell with Clément Ader’s Avion III suspended over it.

Clément Ader (1841 – 1925) was an extraordinary French inventor and engineer whose interests and enthusiasms were diverse. He designed machines for the railway industry, and a bicycle with patented rubber tyres. He filed patents on telephony and invented a stereo microphone so he could listen at home to performances at the Paris Opera. He worked on submarine cables and hydrofoils, but he is perhaps best known as a pioneer in aviation – a word he had a hand in inventing.

In 1873 he began experimenting with a tethered glider to measure drag, wing loading, and glide ratios. His calculations led him to realise it wouldn’t need a very powerful engine to achieve powered flight, so he started designing a lightweight steam engine. In April 1990 he patented his prototype aircraft, a “winged device for aerial navigation called an Avion”. Six months later his avion, inspired by the wings of a bat, with its 20hp 4-cylinder steam engine flew 20cms above the ground for 50 metres. It was more of an uncontrolled hop really, aided by ground effect, hardly controlled sustainable flight. But his heavier-than-air take-off piqued the interest of the army who funded him for his second prototype, which wasn’t very successful, and then a third – the twin-engined Avion III.

It is reported that Avion III managed to fly 300m but not necessarily in a controlled fashion. However there was no proof of flight because this was now a military project and thus Top Secret. Shortly after this, the military’s interest and funding waned, and Ader donated his Avion III to the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, which is how, after being restored by the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace, it is to be found flying above the grand staircase here.

Ground Floor & Church – Transport.

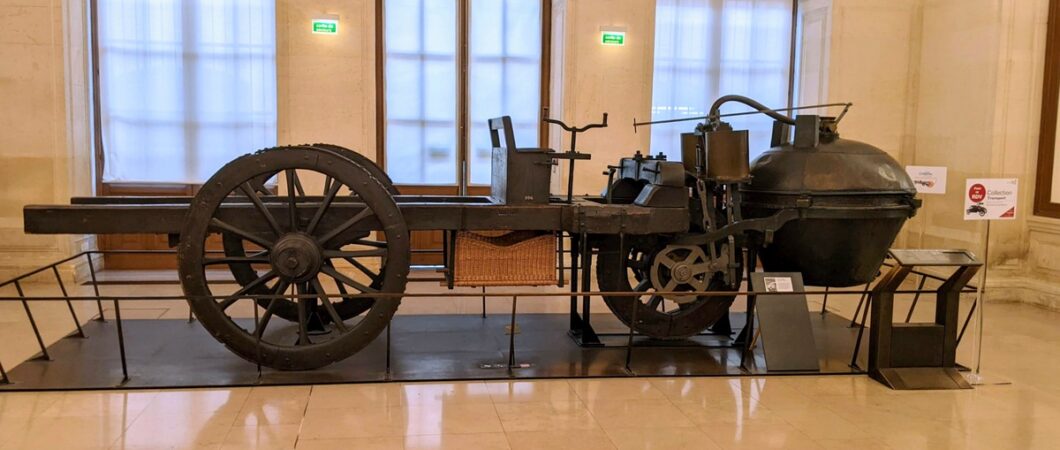

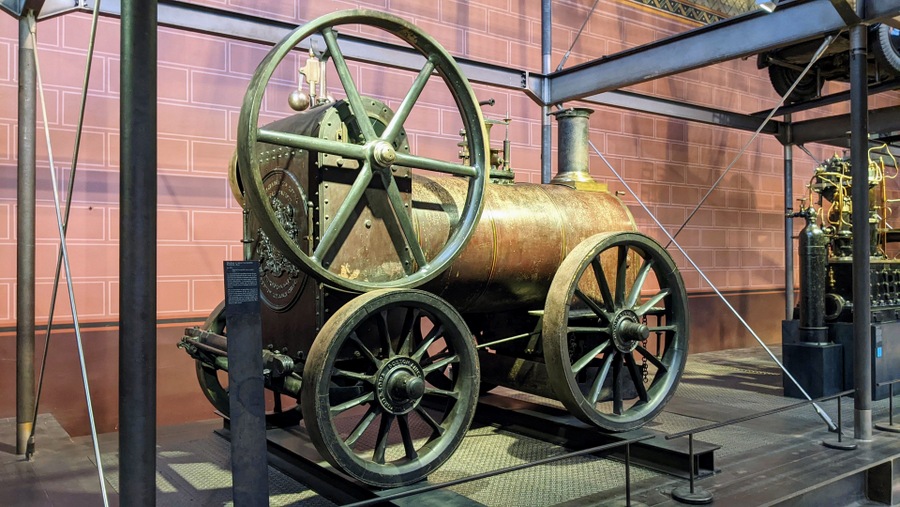

At the bottom of the staircase, standing in splendid isolation is “the world’s first automobile”, although I think I would call it the world’s first truck.

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot (1725 – 1804) was a French army engineer who was interested in developing steam powered vehicles to haul cannon barrels. In 1769 he built a small experimental three-wheeled fardier à vapeur (“steam dray” – a dray was a horse-drawn cart for heavy goods), that used a ratchet system to convert linear piston movement into rotational movement. A year later he built this full-size version, designed to carry four tons at almost 8 kph (5 mph). Unfortunately it barely managed 3.6 kph (2¼ mph), was reportedly unstable in rough terrain, and the boiler kept needing to be relit. The army lost interest and the project was shut down. Cugnot’s fardier was gifted to the museum 30 years later.

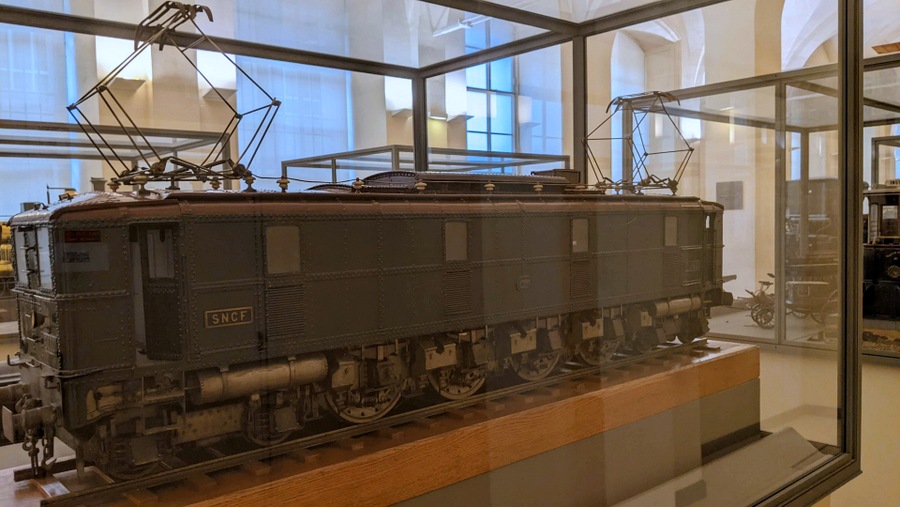

The Transport galleries on the ground floor have an interesting collection of 19th/20th century railway models, ship models, automobiles and bicycles.

The ground floor galleries lead directly into the church, which is a display area still focused on Transport, but also has a couple of Science displays, the most notable of which (and hard to miss) is Foucault’s Pendulum, suspended on a cable inside the spire.

In 1851, French physicist Léon Foucault, used a pendulum to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth. He first demonstrated the principle at the Paris Observatory, before scaling up. He suspending this pendulum with its 28 kg lead ball encased in brass on the end of a 67m cable from the dome of the Panthéon in Paris. It has been at the Arts et Métiers since 1869, swinging slowly over a graduated circle on the floor. Originally released in a straight line, the pattern described on the floor has become an oval path, which you can see change minutely as you watch it.

In the nave of the church are a number of vehicles on the ground floor, two aircraft suspended from the ceiling, and they have a gantry* of staircases and platforms that makes good use of the vertical space by displaying a range of cars, including a 1935 Hispano Suiza and a Peugeot from 1909. The downside is that, when busy, the museum restricts the number of people who can be on the display gantry at a time. It was busy when I was there**, and there was quite a queue of enthusiastic youngsters waiting to climb it. So I never got the chance to explore it – a mission for next time!

The vehicles and artefacts on the ground floor are an odd mix. On the one hand there is a Vulcan rocket motor from the Arianne 5 space launch vehicle. On the other, there is a mobile agricultural steam engine made by the Norfolk based manufacturer Tuxford & Sons in the 1840s. It looks like a traction engine but it doesn’t move under its own power. Tuxford would build their first traction engine in 1857.

Another oddity is Félix Théodore Millet’s petrol engine tricycle 1887. Millet designed a radial engine in the drive wheel weighing just 13 kgs. But also, take a look at that spongy wheel – a forerunner of the Moon and Mars rovers!

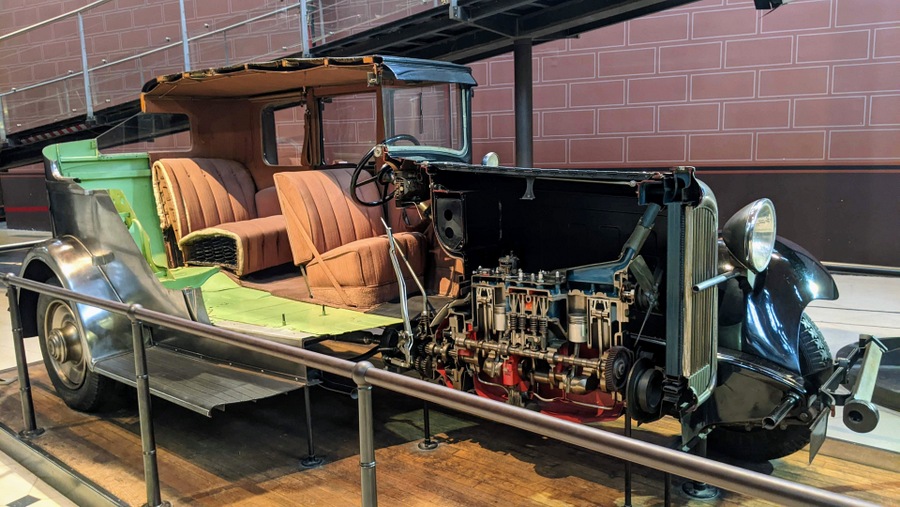

There’s also a fascinating cutaway example of a 1931 Citroën Type C6G, one of the company’s most successful models. The cross-section shows clearly how it was manufactured and how so many of its design features were the gold standard for vehicles of its time and after.

For me, though, this was the highlight of my visit…

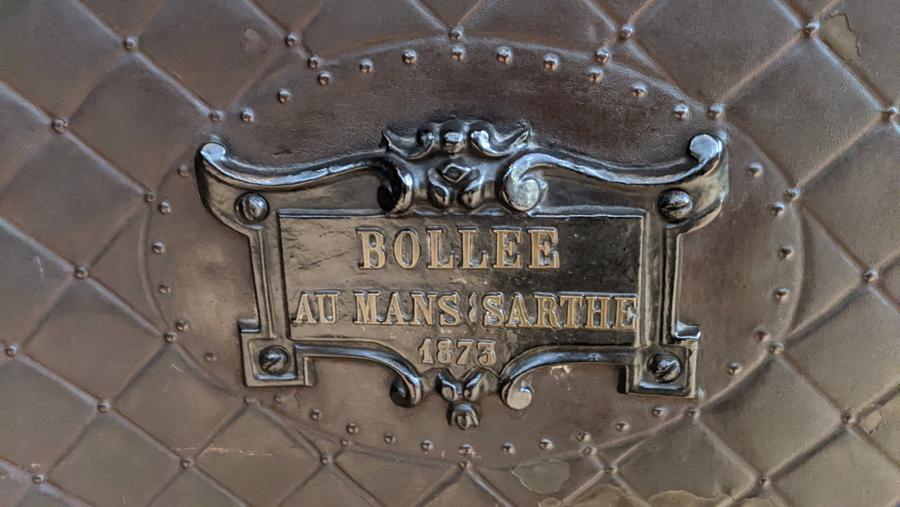

I had learned of Amédée Bollée’s L’Obéissante when visiting the Le Mans 24hr Museum, but I didn’t know it was kept here at the Musée des Arts et Métiers. When I saw it, I recognised it immediately. This was an extraordinary and revolutionary machine.

Amédée Bollée (1844 – 1917) was a bell-founder and inventor in Le Mans. In 1873 he built the first steam powered road vehicle, which he referred to as a ‘locomobile’, which was fair enough since the word ‘automobile’ (“that which moves by itself”) wasn’t invented, or at least listed, by the Académie Française (attributed with a male gender), until two years later.

It was capable of driving 12 passengers plus a driver and a fireman at speeds up to 40 kph, and could cruise, moderately comfortably thanks to its 4-wheel independent suspension, at 30 kph. Its chain belt drive system had three gears – slow, fast and reverse. With its low gear and its two 2-cylinder steam engines it could climb 12% gradients.

In order to allay fears that this 4,800 kg machine might run out of control, Bollée named it L’Obéissante (The Obedient) and successfully applied for permission from the authorities to drive it on the road.

On 9 October 1875, he drove his passengers the 230 kms from Le Mans to Paris in 18 hours, including stops for water and meals!

* I’m not sure ‘gantry’ is quite the right word for this structure, but I can’t think of a better one!

** I had to nip back to get photos of it looking quieter.

Apology: I’m sorry about all the glass reflections. I try to get angles that reduce the glare, but some museums are just not good at this.

Declaration: I was visiting Paris on a pleasure/research trip. Museum entry was complementary with my press card.

Factbox (2024)

Website:

Musée des Arts et Métiers

Getting there:

60 rue Réaumur

75003, Paris

Getting there is easy. Take the Metro to Réaumur-Sébastopol (Lines 3 or 4), OR Arts-et-Métiers (Lines 3 or 11). Both are close to the museum. By bus, you want the 20, 38, or 39.

Entry Price:

| Adult | € 12.00 |

| Under 26 | Free |

There are reductions for large families with an SNCF card, and Paris Museum Pass holders.

Opening Hours:

The museum is open year round, Tue – Sun, 10.00 – 18.00. On Fridays it stays open till 21.00.

It is closed on Mondays, and on 01 Jan, 01 May, and 25 Dec.

Two things to note:

The museum is, quite rightly, extremely popular (220,340 visitors per annum) especially with school groups during term time. I recommend visiting around mid-afternoon, by which time many groups have departed.

Thanks to a high level of security in the Paris region at the moment, you can’t take large bags/suitcases. Only small day bags, which you have to keep with you. The only items you can store in the cloakroom are coats and umbrellas.