The Air & Space Museum (Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace), sprawled around the magnificent art deco terminal building at Paris’ former passenger airport, Le Bourget, is France’s premier aviation museum.

It’s huge, and well worth the journey to the outskirts of Paris to visit. Only, make sure you set aside plenty of time because there’s a lot to see!

The Layout

Le Bourget is still an operational airport, but no longer for commercial traffic. Instead it serves as a private aviation hub, and as the venue for the bi-annual Paris Air Show.

In the 1970s, the transfer of international airline traffic to Orly and then Charles deGaulle airports, freed up the glamorous old terminal building, numerous hangers and a large chunk of tarmac for the museum.

Pioneers Hall

The Pioneers Hall is in the elegant north wing of the old terminal, and is the obvious starting point for a visit to the museum. There are some amazing (and rickety!) aircraft in here.

One of the first on display is this supremely elegant 1912 Morane-Saulnier G-type. It looks like it could be in a fine art museum.

The pencil-thin Antoinette VII was a favourite of French aviator Hubert Latham, who was almost the first to fly across the Channel in one of these (he made two attempts), but Louis Blériot beat him. The front fuselage of this aircraft is original. The rear was rebuilt and the canvas replaced and re-doped.

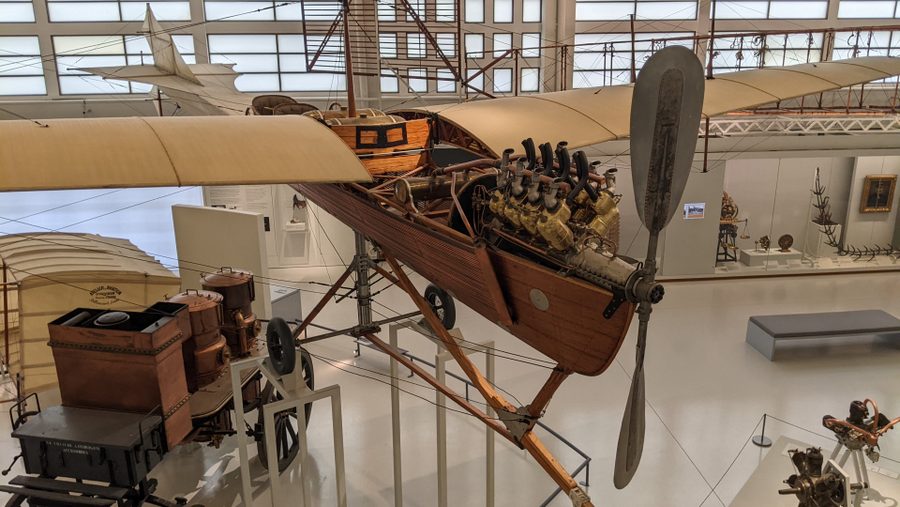

This extraordinary machine (below) is hard to make out in my photo, with all the background clutter.

It is French engineer, Henri Fabre’s Hydroavion, and it became the world’s first seaplane, when on 28 March 1910, with no piloting experience, he took off from the Étang de Berre lagoon outside Marseilles. In fact, he got airborne four times that day and his longest flight was 600 metres. This historic photo is not of him on that day, but rather his Hydroavion being flown by Jean Becue outside Monaco a year later.

Fabre’s design was unusual to say the least. It was a canard controlled aircraft with a push propeller, fabric wings with structured ash wood leading edges, and his own design of aerofoil floats, which at an altitude of just over 2 metres (6½ ft) harnessed the ground effect to add greater lift. The 50-horsepower Gnome 7-cylinder rotary engine not only got him ‘unstuck’ from the water, but also gave him a cruising speed of 55mph. This is a replica built by a team in Toulouse to mark the 100th anniversary of Fabre’s achievement.

The aircraft in the museum is original. The signage notes that the fabric covering and dope have been “redone”.

This Farman HF-20 built in 1912, is the last aircraft in the Pioneers Hall and marks the crossover into the Great War, in that it was the first aircraft to be designed for a specific military purpose – reconnaissance.

Great War Hall

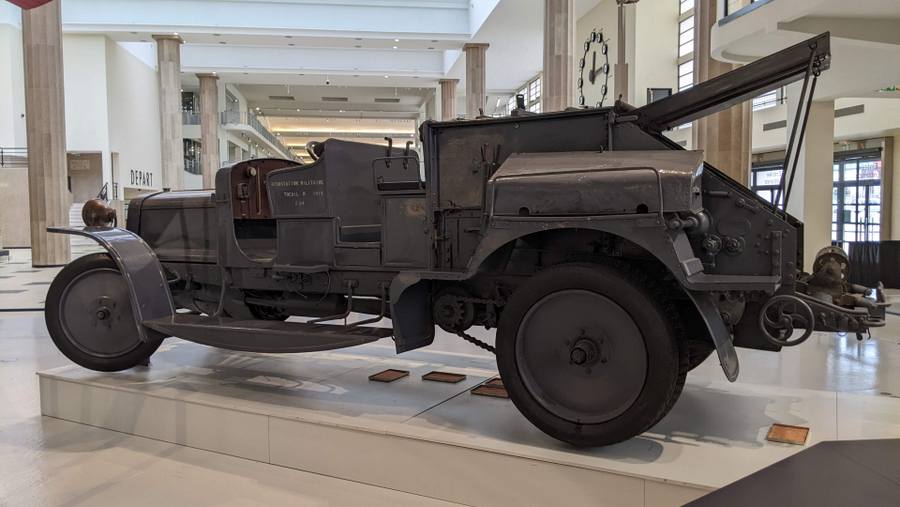

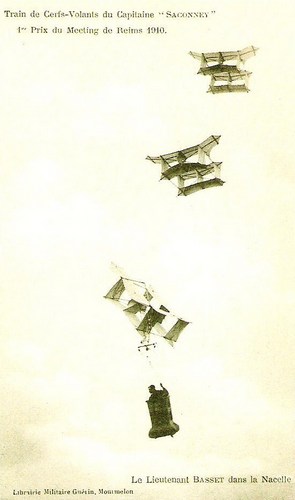

The Great War Hall occupies the other wing of the terminal building, and it starts off not with an aircraft but with an automobile.

This is an army aerial observation post vehicle produced by Delahaye. It had a winch with 2000ft of cable to which a string of large kites were attached, and a one man basket. Obviously, unlike a balloon, it could only be used on windy days to get a man with binoculars and a telephone, up in the sky over the battlefield.

You have to hope it would be a steady wind. Even then it would be a bouncy ride for the occupant, without the confidence a balloon might give. I doubt they had many volunteers.

Something you don’t see often… a gondola from an R-class Zeppelin.

This is the rear engine gondola from Zeppelin LZ-113. It had two engines inside which powered outboard propellers. LZ-113 first flew in February 1917, and was operational, flying numerous reconnaissance and bombing missions, before the war ended in November 1918. In 1920 it was sent to France as part of war reparations.

Does that corrugated metal (above) look familiar? Something of a trademark for Junkers aircraft. Most people would recognise it from the WW2 era Junkers 52 transport aircraft. This is a Junkers J-9 designed for ground attack and, as a low wing monoplane, very modern for 1918. Up until this point, aeroplanes had been mostly biplanes, and all were made of wood and canvas.

Of course canvas is nice and easy to, literally, ‘patch up’ when damaged, but so too was Junkers’ revolutionary corrugated light-weight alloy. You simply replaced panels. This J-9 has had many replacement panels!

The Great War Hall has some important warplanes on display. The 1915 French twin-engine Caudron G.4 was used by the British, Russian and Italian air forces. It had a fast climb rate but was used by the British as a bomber rather than an interceptor. They are rare but there is one Cauldron G.3 in the RAF Museum, Hendon, and a 1917 G.4 at the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in the USA.

There’s a 1913 Maurice Farman MF.7 observation aircraft from the beginning of WW1, and a 1918 Fokker D.VII, the enemy fighter most respected by the Allies. In between, there’s a Breguet XIV bomber/reconnaissance aircraft, and a collection of WW1 engines.

Space Hall

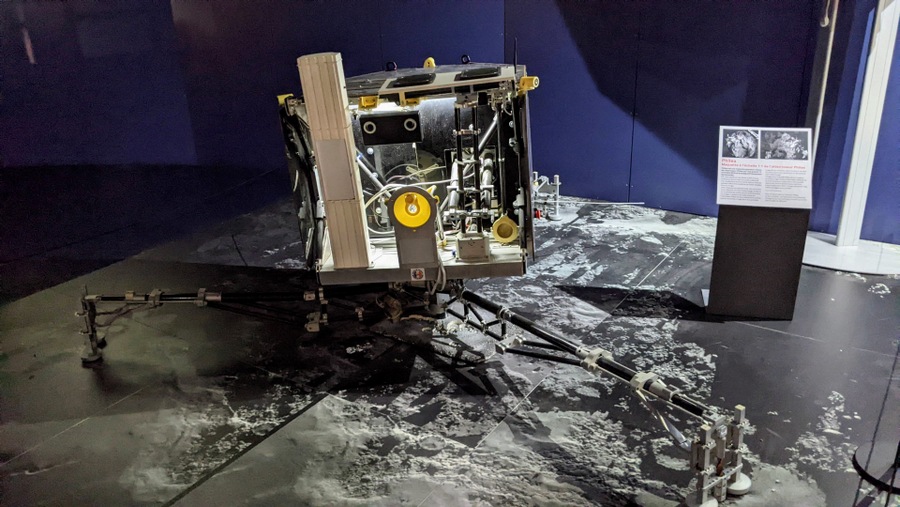

The Space Hall is cavernous with multiple levels of gantries and walkways climbing up and up. I’m not sure what I was expecting, but I was amazed at this hall and spent ages in here, soaking it up. There are plenty of rockets & missiles, from Arianne to Polaris, and plenty of space vehicles, like this classic…

I always though the designer of the rather ludicrous-looking Lunakhod 1 got his/her inspiration from a kid’s pram! This was the USSR’s remote-control lunar rover sent to the moon in 1970 – the year after Apollo 11 landed. As it turned out, it was far from ludicrous. After landing and deploying successfully in the Sea of Rains, it then spent almost a year travelling some 10 kilometres, taking over 20,000 photographs and conducting numerous soil analysis experiments. This, of course, is a replica. The real thing is still up there, and it never bumped into any American astronauts… as far as we know.

That is the interesting thing about the Space Hall. Almost nothing in here is actually real. It’s all reproductions. All the actual satellites and space vehicles are still up there. Rockets & missiles tend to be full of horribly corrosive and explosive chemicals, so all those in the Space Hall are either inert practise missiles or just models.

This is a 1:1 scale model of Philea, the European Space Agency (ESA) vehicle that landed on comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenkov in 2014. There was a certain amount of mystery to the event. Philea sent some images back, but communication was intermittent and its parent, Rosetta, couldn’t see where it landed. Eventually they found it. It had fallen sideways into a crevice, which explained why its transmissions were patchy and its solar panels weren’t charging it up.

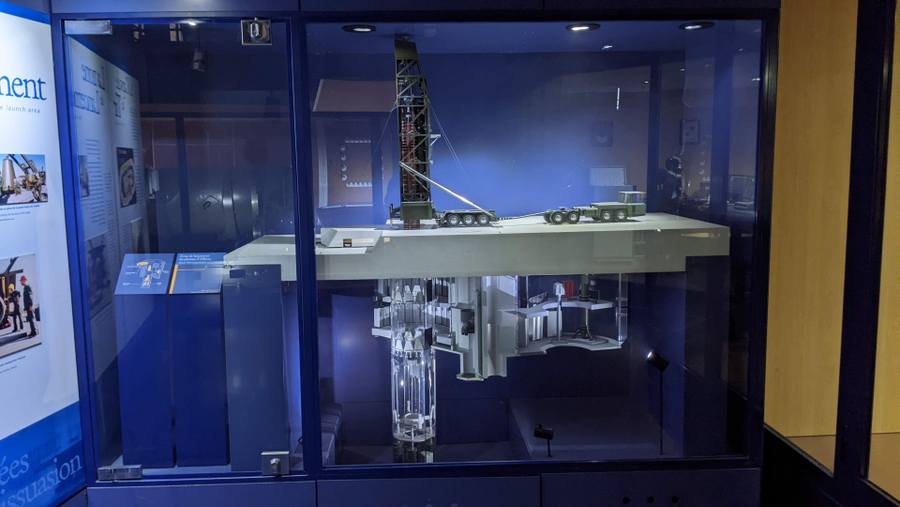

France, of course, was and is an independent nuclear power. During the Cold War its Dassault Mirage IV (See Concorde Hall) supersonic strategic bombers carried nuclear bombs and its Redoubtable class submarines carried nuclear ICBM missiles. What’s less well known is that, like the US, it also had land based ICBMs housed in silos on the Plateau d’Albion in the Alpine foothills of southeast France from 1971 to 1996. The missile facility had 18 silos and two underground command bunkers, each responsible for 9 missiles although either could launch all 18 if there was a problem.

The silos and two fire control stations have been dismantled and the former ‘Air Base 200’, which served as a support base for the installations, is today used by the 2nd foreign engineering regiment of the Foreign Legion as well as by a DGSE listening station.

Inter-War Hall

The Inter-War Hall has been closed over the last few months in order to accommodate part of the museum’s latest temporary exhibition The Roaring Twenties of Aviation, which opened 24 October and runs to 3 March 2024. The exhibition focuses on the cultural and societal impact of aviation in those two revolutionary decades between 1919 and 1939. The two parts of the exhibition, one in an exhibition room in the Grande Galerie, and the other in the Inter-War Hall, tell the tale of those years in eight sections:

- The birth of commercial aviation,

- The long distance challenges – conquering the world

- Aviation in the society of the Roaring Twenties

- The influence of aeronautics on the arts

- The portrayal of aviators – challenges and heroism

- The art of travel

- Aviation as a symbol of power

- The threat of military aviation

It is a chance for the Museum to show off some 300 objects from its own collection, plus some artefacts on loan from other major non-aviation museums, including posters, toys, fashion, photographs, and material from their printed and audio-visual archives.

Meanwhile, most of the aircraft in the hall remain, at least the suspended exhibits do.

Here, on the ground, is some more of that Junkers corrugated alloy. This is the F-13 light transport aircraft. It was designed to carry five passengers – four in the cabin, one in the open cockpit with the pilot. I suppose we might call that ‘steerage’! It first flew in June 1919.

Suspended dramatically in the air, performing a loop, is the Morane-Saulnier 230, a dual seat trainer intended to teach students combat techniques. It first flew in 1929.

The Breguet 19 TF is a record breaking endurance aircraft with extra fuel capacity. On 1 September 1930, Dieudonné Costes took off from Le Bourget and landed at Curtis Field outside New York 37 hours and 12 minutes later. Not sure he’d make it now with all that dust on her! 😉

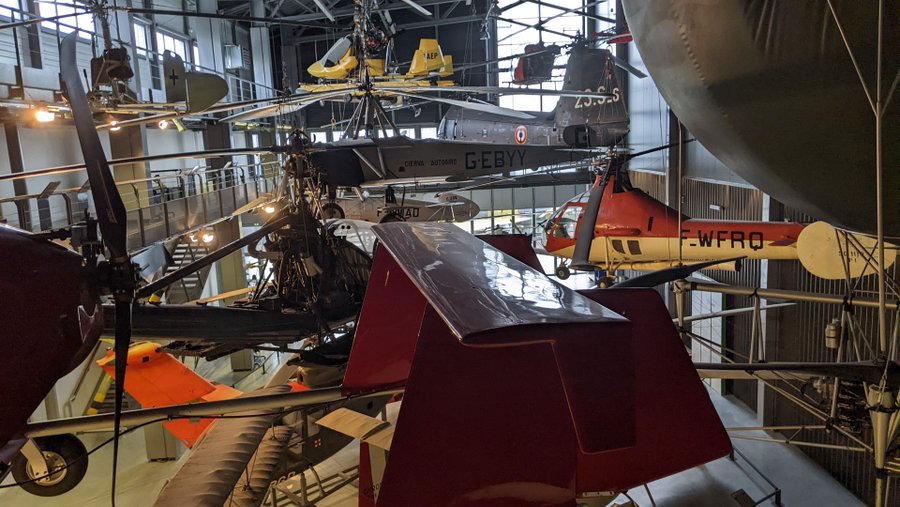

Helicopter Hall

This hall is busy with helicopters and auto-gyros. It is difficult to separate some of them and their signage out from the confusion of other machines around them. Some are to be expected, like the Sikorsky H-34A, the Cierva C-8 autogyro (this one is actually the C-8L-11 version, ordered by the British Air Ministry in 1928), the Focke-Achgelis Fa-330 tethered U-boat autogyro, and the French Army Aerospatiale SA-341 Gazelle. But there are some standout machines.

There is a Sud-Aviation SA-319B Alouette III helicopter, a mainstay of the French military and rescue services, particularly at high altitudes. It first flew in Feb 1959. By 1979 when they stopped manufacturing, over 2,000 Alouette IIIs had been built. This one was with the Gendarmerie for 35 years, based in the Alps in Megève and Chamonix first, then in Briançon. Thirty five years seems to me like a long time to be operational, but her signage says she flew 13,478 hours and saved 16,087 people. If it really was 35 years, that would be an average of 8.8 persons rescued per week!

The Piasecki H-25/HUP Retriever is a remarkable tandem helicopter. These were produced for the US Army and Navy (the Navy version had folding blades) between 1949 and 1954, so this is really a very early helicopter. The first British tandem, the Westland Belvedere, wasn’t produced till the 1960s. The H-25 model was the first helicopter to loop-the-loop and the first to be equipped with an autopilot, which was important for the naval rescue variant because it helped keep stationary in the hover, which is why the French navy bought 15 of them.

Perhaps the most interesting machine in the hall is the Pescara prototype helicopter. Argentinian engineer Raul Pateras Pescara started experimenting with helicopters in Spain in 1916, but it wasn’t until 1922 in France that he achieved some success with his model 2 aircraft.

It looks like a complicated machine, but essentially it featured two x 3 bladed contra rotating rotors… only, each of those blades was actually two blades paired as a biplane. His model 2F hovered for one minute at a height of one metre. Two years later it flew the best part of a kilometre (736m) at 13 kph.

The important thing about Pescara’s machines were his control systems. He was the first to develop a flight control system using cyclic and collective pitch control. The rotor mast could tilt slightly, giving it directional travel.

Cocarde Hall

The Cocarde Hall and the Prototypes Hall are two halves of the same hanger, with a mezzanine balcony area separating them.

A Cockade is “a knot of ribbons, or other circular, or oval-shaped symbol of distinctive colours which is usually worn on a hat or cap. The word cockade derives from the French cocarde, from Old French coquarde, feminine of coquard, from coc, of imitative origin. The earliest documented use was in 1709.” – Wikipedia. Who knew?!

In this case it refers to the dramatic fanned out display of post 1950s French and American jets used by the French military: a Dassault MD-450 Ouragan, Republic F-84, Mystère IV, F-86 Sabre, F-100 Super Sabre, Super Mystère B2, Mirage F1, Mirage 2000, Sncase SE-535 Mistral, and a North American T-6 trainer.

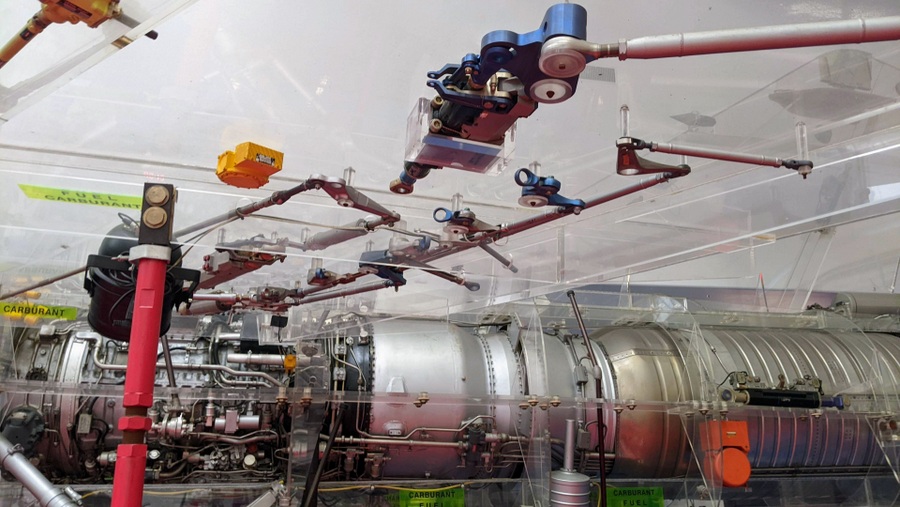

There’s also a really interesting exhibit in here; a transparent Mirage F1 fighter. It’s fascinating to see the engine and cockpit components, and to trace the fuel and electrical connections, but I think the connecting rods and actuators in the wings for the control surfaces are the most interesting aspects. You know what jet engines look like and cockpits look like, but you never really see inside the wings!

Prototypes Hall

This hall is fascinating. There are some extraordinary and bizarre experimental aircraft in here.

The Sud-Ouest SO-6000 Triton was France’s first jet aircraft. It was developed in secret during the German occupation of France in WW2 and first flew in November 1946. It was the brainchild of French aeronautical engineer, Lucien Servanty, who went on to work on the Caravelle and Concorde. It was designed as a 2-seater training aircraft but only five were built post-war; by then jet technology had already moved on. The prototypes were fitted with Junkers Jumo engines at first, since the Servanty’s design bureau were basing their work on German research papers, but then the Rolls-Royce Neme engine was used. This Neme-powered aircraft is the only surviving Triton.

You know that scene in the first ‘Men in Black’ movie, when Tommy Lee Jones hands Will Smith a tiny little ray gun, the ‘Noisy Cricket’? Well the tiny Payen PA-49 Katy reminds me of that! It’s just 5.1m long with a wingspan of 5.3m. How the test pilot, T. Ochsenbien, managed to get into it, let alone get it airborne on 15 Dec 1953, I just don’t know. But, rather like the Noisy Cricket, the Payen Katy performed better than its size might suggest. Over a test programme of 300 flights, it impressed all its pilots with its handling characteristics.

The Sud Ouest SO-9000 Trident I, which first flew in March 1953 was a mixed-propulsion aircraft, powered by a rocket engine in the fuselage and two wingtip-mounted turbojet engines. Designed by our old friend Lucian Servanty, this prototype and its successor, the more powerful Trident II, were developed as part of a programme to develop a high speed, high altitude interceptor. By 1956 the Trident II had broken several height and speed records, reaching a speed of Mach 1.96 at a height of 19,100 m (62,664 ft). Two years later it reached 26,000 metres (85,302 ft), and set a record rate of climb – 15,000 metres in 135 seconds! This aircraft on display is the first Trident I prototype.

Also on display are a Dassault Mystère IVa fighter-bomber, the first transonic aircraft to enter service with the Armée de l’Air (French Air Force). This particular aircraft No. 01, made the maiden flight on 28 September 1952 (Yes, you are not hallucinating. There is another Mystère IVa displayed in the cockarde a few metres away.) There’s a Dassault-Breguet Mirage G8 swing-wing supersonic (Mach 2) bomber. The G8 or “Super Mirage” was a variant that never went into production for budget reasons. This was the first G8 to fly. And there’s an interesting streamlined twin-prop aeroplane, the Hirsch H-100 from 1954, designed specifically to test control surfaces in gusts caused by rapid or uneven changes in airflow.

The star exhibits in the prototypes Hall have to be René Leduc’s ramjets, the Leduc 0.10 and Leduc 022. The defining feature of these two aircraft is the cockpit located inside the engine nozzle!

The Leduc 0.10 was designed by French aeronautical engineer René Leduc in 1938, based on a surprisingly ahead-of-its-time ramjet concept patented by another engineer, René Lorin in 1908. Leduc’s 0.10 prototype was built in secret in the Breguet Aviation factory under the noses of the German occupiers during WW2, and completed in 1947.

When at speed, a ramjet compresses the air entering the intake, adds fuel, and ignites it. It needs to be travelling at speed to work, it can’t work from a standstill. So the Leduc 0.10 had to be carried aloft on the back of a large passenger plane and then released at high altitude in a shallow dive. It did this and successfully fired up the engine for the first time in April 1949, flying for 12 minutes and reaching a speed of 680 km/h (420 mph). On later flights it reached Mach 0.85. Three prototypes were built, two were wrecked, the one on display here is the third.

The Leduc 022 was a mixed propulsion aircraft, using a jet turbine to take off, and switching to the ramjet at speed. It was designed to address the air force’s requirement for a fast climbing interceptor, which it certainly was. It could climb to 25,000 metres in just 7 minutes, and achieved a top speed of Mach 1.15.

Unfortunately the Armée de l’Air was looking for budget cuts in the late 1950s. It didn’t really need an exotic supersonic interceptor. It needed ground attack jets like the Dassault Mirage III for its counter-insurgency wars in former colonies, and the Leduc programme was axed in Feb 1958. Sadly that was the last aircraft René Leduc designed. He turned his hand to designing and building hydraulic systems for construction diggers. There are more details on the Leduc ramjets here, and a video of the Leduc 022 in flight.

There is an open area, a taxiway in effect, between the Space, Interwar, Helicopter, Cocarde and Prototypes halls and the two large hangers housing the 2 x Concordes and the WW2 aircraft. I’ll call it…

The Taxiway

There are four jets on display here. As with all aircraft left exposed to the elements, they are looking less glamorous than they once were. They are the classic Swedish Air Force Saab J35A Draken, still an amazing looking aircraft.

Behind it sits a 2-seater Saab 37E Viggen with canards that have their own control surfaces. Normally a canard is a single plane, not jointed with a flap/aileron, but this gives the Viggen a short landing capability and the Swedes are keen on using their roads as runways. What is it with the Swedes? They always seem to go their own unique way when it comes to military design & construction. Look at their tanks! No other nation came up with a Cold War tank design like the Stridsvagn 103 “S-tank”!

The other two jets on the taxiway are Soviet.

There’s a Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23 ML (NATO name ‘Flogger’), the Mach 2, variable-wing successor to the MiG 21. It first flew in June 1967 and thereafter was manufactured in huge numbers (5,800) and exported to over thirty countries. This aircraft was in the East German air force. One thing I’ve always liked about the Mig-23 is the big chunky bent-leg undercarriage. I doubt much change was needed for the MiG-23 K carrier variant. Those legs look like they could take a real pounding!

The last of the four is a Sukhoi Su-22M-4 (NATO name ‘Fitter’), again from East Germany. This variable-wing ground attack aircraft first flew in August 1966 as the Su-17, and with a fixed wing. The Su-22 is a later export variant of the Su-17. It was designed to fly low and fast (max speed Mach 1.7).

Hall Concorde

Ta-dah! Not one, but two Concordes in this giant space! And they look stunning (as Concordes always do)!

They are: one of the prototypes (F-WTSS) used for testing, and one of Air France’s Concorde fleet (F-BTSD). They have been parked nose by nose, so that you can walk through the flying testbed first and then cross over to the Air France Concorde and walk through her before exiting at the tail. Access to the Concordes is an extra on your museum entry ticket.

They both have records. Concorde F-WTSS Prototype first flew in 1969. The next year, on its 102nd test flight, it reached Mach 2 for the first time and flew at that speed for almost an hour. In 1995, Concorde F-BTSD flew around the world in 31h 27m 49s (including stopovers). It was in the air for 22 hours, 46 minutes, of which 18 hours 46 minutes was supersonic – a world record.

The Concorde hall is pretty enormous so it’s no surprise that the museum has put a couple of extra exhibits in the corners. The first is a Dassault Mirage IV A supersonic nuclear bomber. Sixty-six were built and, carrying a 60-kiloton nuclear bomb, were part of France’s nuclear deterrent from 1964 to 1986, when the Mirage IV A was replaced by the Mirage IV P variant.

The second aircraft exhibit is a badly damaged French Air Force SEPECAT Jaguar. Jaguar A.91 was hit by a missile while attacking Al-Jaber during Operation Dessert Storm on 17 January 1991. Amazingly it survived and so did its pilot. The air force kept it as an instructional tool in damage repair for engineers, until 2021 when it was donated to the museum.

Next door is the…

World War II Hall

The presence of the Vietnam War era Douglas AD4 NA Skyraider in a WW2 hanger was a little baffling, but it is a fantastic aircraft and, even with its wings folded, there isn’t enough space in the Cockarde Hall for it. To be fair, the Skyraider first flew in March 1945, just months before WW2 ended, so I suppose it just scrapes inside the technical definition! From 1959 onwards, the French bought over 100 Skyraiders which they used in the Algerian War. If you want to see an airworthy Skyraider, visit the Salis Flying Museum 40 kms south of Paris.

I was a little disappointed by the WW2 hall. There’s the ubiquitous C-47 Skytrain, a Focke Wulf Fw-190 A8, a Republic P-47D Thunderbolt a North American P-51D Mustang, a very shiny Supermarine Spitfire Mk16, and a V2 flying bomb. So nothing particularly out of the ordinary.

Except…

The most interesting aircraft in here is the Dewoitine D-520. This was France’s most up-to-date fighter when WW2 broke out. It had a top speed of 335 mph and was armed with a 20mm cannon. First flown in October 1938, it was only just in service with the French Air Force in 1940 as the Germans invaded.

The few D-520s in service, barely saw action against the Lufwaffe before the Battle of France was over and the armistice signed. After that, it’s fair to say, it had a confused history. Some were spirited away to North Africa to avoid capture by the Germans. Some ended up with the Free French Air Force, some with the Vichy government forces who used them to attack Allied aircraft during Operation Torch in November 1942. Some D-520s found their way into the Luftwaffe and the Italian Regia Aeronautica who attacked Allied bombers over Italy. Then, when the Italian Armistice was signed in September 1943 and the Italians joined the Allies those D-520s were turned on the Luftwaffe. The Luftwaffe in turn, gave some of their D-520s to their allies, the Bulgarian Air Force, to be used against the Allies. So the Dewoitine D-520 was pretty much flown by everybody, against everybody!

This D.520 is actually in flying condition, but not licensed to fly. The last flying 520 crashed at an airshow in 1986, so now, out of 891 that were built, there are only two on static display: this one and one at the Musée de l’Aéronautique Navale in Rochefort.

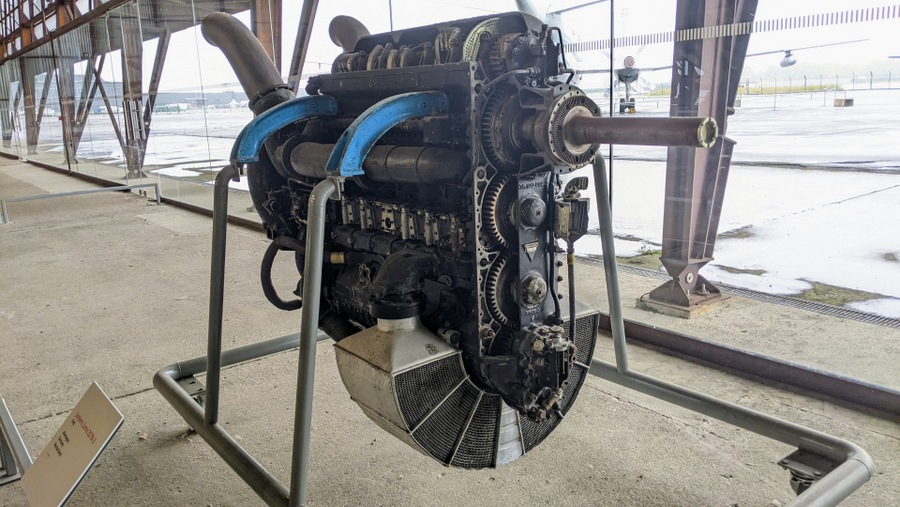

The WW2 Hall also has some interesting aero engines. There’s a fabulous Napier Sabre II, forerunner of the fabulous Sabre III. There’s a Daimler Benz DB603 A2 , and a Junkers Jumo 213, used in the Junkers Ju 188 (successor to the Junkers 88), Focke-Wulf Fw 190D, and the long-nosed Focke-Wulf Ta 152. Most interesting is the super thin Junkers Jumo 207 B2 inline diesel engine. Its weird configuration had six cylinders and 12 opposed pistons (i.e. 2 per cylinder) operating a two-stroke cycle with a supercharger. It could output the same power from sea level to 7,900 m (26,000 ft) and powered Junkers Ju 86 reconnaissance/bomber aircraft up to 15,000 m (49,000 ft).

The last indoor space, if you don’t count the Planetarium, is the…

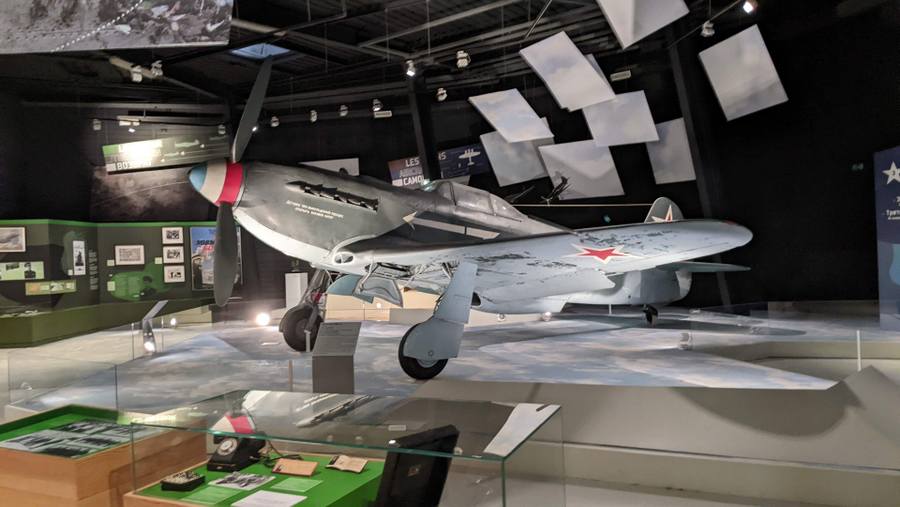

Normandie-Niemen Hall

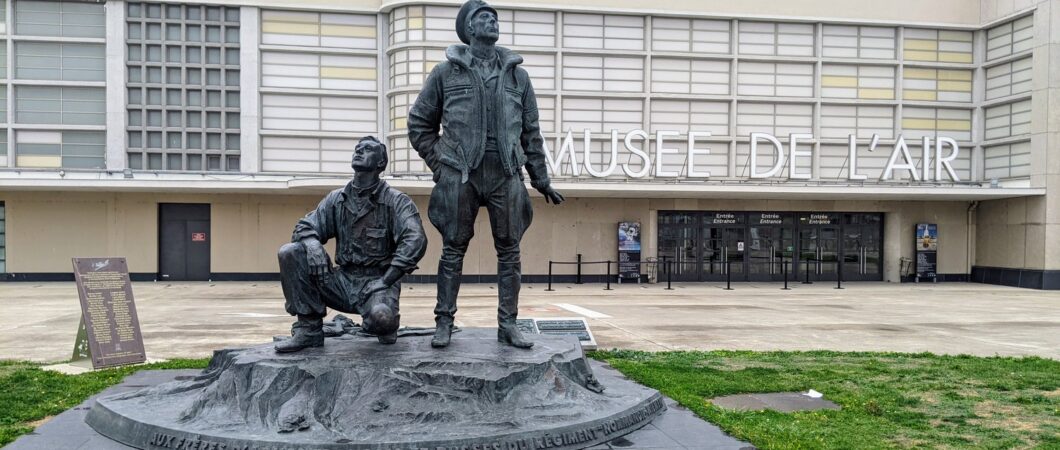

This is one of the best things at the Air & Space Museum. The Normandie Nieman squadrons of Free French pilots flying with the Russians in WW2 are legendary, and as I heard a historian saying recently, went a long way to expunging any guilt, and restoring the national pride of a defeated nation. The statue of two pilots at the front of the museum (feature image) is a tribute to them.

General de Gaulle, commander of the Free French forces, was keen to see Frenchmen fighting on all fronts. So in 1942, he agreed with the Russians, to send a French fighter group to fight with the Red Army on the Eastern Front. Fourteen pilots and 58 ground crew were formed into the initial unit of Fighter Group 3 ‘Normandie’, based in the Lebanon.

(The name was accidental. Their commander, Joseph Pouliquen had wanted to use his home region, Brittany, but it was already in use with a Free French bomb group. So, they picked Normandy instead. Later, in July 1943 the group helped breach German defences on the Niemen river in Lithuania, for which the Soviets awarded them the name ‘Niemen Regiment’. So they became the ‘Normandy-Niemen’ regiment.)

The group travelled to Russia via Tehran in November 1942. It must have been a real shock moving from the Middle East to an airbase northeast of Moscow in the middle of winter!

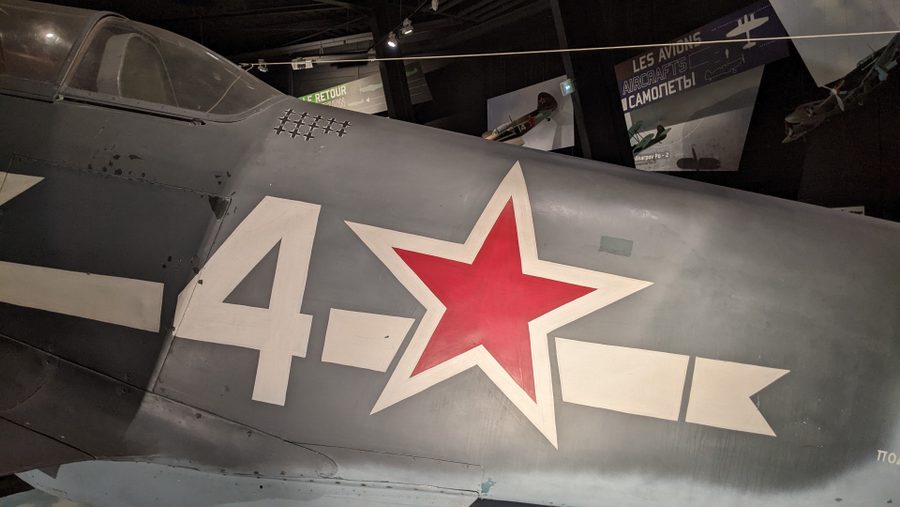

During their service from 1943 to 1945, 100 Normandie-Niemen pilots destroyed 273 enemy aircraft and 37 ‘probables’ during 5,240 missions. On the ground they destroyed 27 trains, 22 locomotives, 2 E-boats, 132 trucks, and 24 staff cars. They lost 42 pilots.

The hall is a small circular building, with a Yakovlev Yak-3 fighter as the centrepiece. The rest of the space has information panels, displays of photographs, documents, personal artefacts, and items of uniform from the French pilots of the Normandie-Niemen squadrons in Russia.

The Yak-3 belonged to pilot Lt Roger Marchi. He was flying it on 20 June 1945 when 37 Yaks returned to Le Bourget at the war’s end. It was a triumphant ceremony that started with a flypast over Paris and some aerobatics by Marchi, and ended on the ground with a revue, speeches, flowers and champagne before an audience of French ministers and dignitaries, plus senior Red Army Air Force officers who had flown in on C-47s with the Normandie ground crew and mechanics.

If you can find a copy (it’s out of print) there’s a very good book on the Normandie-Niemen squadrons ‘French Eagles, Soviet Heroes’ by John D. Clarke, published by Sutton Publishing in 2005, ISBN 0-7509-4074-3.

The Apron

Outside, on the apron is where the museum has the BIG stuff, starting with the two enormous Ariane space rockets, Ariane 1 and Ariane 5 (both replicas). The Ariane programme was started by the European Space Agency (ESA) from its launch base in French Equatorial Guinea in 1973. The mission was to enable European countries to launch their satellites into space. Ariane I, developed and built by the French space agency CNES, first launched on 24 December 1979. From then to the end of its service in 1986, Ariane 1 made eleven launches (9 successful, 2 failures) delivering 14 satellites to orbit.

Ariane 5 had 82 consecutive successful launches between April 2003 and December 2017. Its successor, Ariane 6, is still in development, delayed by the impact of COVID. Arianespace, which has been operating the launch programme since 1986, now offer its customers a choice of launch vehicles Ariane 5 & 6 and Vega & Vega C. They were also offering Soyuz until recently as part of a joint co-operation programme with Russia but it was suspended in March 2022 in line with European sanctions on Russia.

The other two ‘biggies’ on the tarmac are the Boeing 747 and Airbus A380 airliners. The B747 is one of the aircraft that’s accessible to the public. The giant Airbus A380 arrived at the museum in 2017 and is not yet ready to be open to the public, but you can get up close and walk around it.

Personally, I’m delighted to see my favourite aircraft, the Breguet Br-1150 Atlantic long-range maritime reconnaissance aircraft. I’ve talked about this before. It’s hard to put my finger on it exactly, but I love aircraft that are specifically designed for a role, and look the part! Others that might fall into that definition are the A10 gunship (and the A4 Skyraider) or the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk, for example. Anyway, the Atlantic was ordered as a NATO replacement for the Lookheed Neptune. It first flew in 1961, and was operational with the French, Italian, German, Dutch and Pakistani navies. In 2012 it was upgraded to the Atlantique 2 – more or less the same airframe and engines, but with new capabilities, new weapons systems, and electronics. It is expected to remain in service with the French Navy until 2032. You can’t keep a good plane down!

There’s a small prop plane on the tarmac which I took to be a transport/utility aircraft, but it turns out, although that was its intended role with the French Army and Navy when the Nord-Aviation Frégate first flew in 1962, but in 1977 the Navy turned theirs into the Nord 262 E, another maritime surveillance aircraft. It was operational to 2009.

One one side of the tarmac there is a row of three aircraft covers with some fast jets on display inside. The first cover has two jets; Dassaults’ Étendard IVM and its successor, the Super Étendard of Falklands war fame. (In 1982 the Argentinian Air Force sank two British warships with their Super Étendards) Actually, this one on display is a SEM, a Dassault Super Étendard Modernisé, upgraded in 1990.

Under the middle cover is the Dassault Rafale A prototype that was first flown in 1986 and demonstrated a month later at the Farnborough air show. There were long delays getting it into service with the French air force and navy, but it is now established as a successful multi-purpose jet with export sales to seven countries, and potentially six more.

The last cover has a pair of SEPECAT Jaguars. Ask me what SEPECAT stands for – you’ll wish you hadn’t! Société Européenne de Production de l’avion Ecole de Combat et d’Appui Tactique (told you!). SEPECAT was a joint Anglo-French manufacturer (British Aircraft Corporation and Breguet). The Jaguar was intended as a subsonic trainer, but the spec changed and it became a supersonic assault aircraft. It flew with the RAF and French Air Force in the 1990 Gulf War (See the Jaguar exhibit in the Concorde Hall, above), and was exported to India, Ecuador, Nigeria, Oman. The pair displayed are a Jaguar A which joined the French Air Force in 1973 and retired in 2005, and a Jaguar E, two-seater trainer.

There are a small number of other aircraft on the tarmac at any one time, but the aircraft displayed do tend to change position and get swapped in and out. Looking at a recent image of the tarmac, it’s not clear if the elegant Sud-Aviation Caravelle passenger jet is currently on display.

The Caravelle was a successful short range regional French jet airliner that first flew in May 1955 and was in service from 1959 with 93 airlines all over the world including Air France, SAS Scandinavian Airlines, United Airlines, China Airlines, but never British Airways. Production ended in 1972.

I’m not going to tell you that it was the first aircraft I ever flew on, because that would be an embarrassing age revelation…oops.

Declaration: I was visiting Paris. Museum entry was complementary with my press card.

Factbox

Website:

Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace

Getting there: Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace

Aéroport de Paris – Le Bourget

CS 90005 – 93352 Le Bourget Cedex

France

Le Bourget is a little way out of town. Not as far north as the main airport, Charles de Gaulle (CDG) but still, depending on the time of day, it’ll take 50 mins to 1hr 15mins from the centre of Paris if you are driving or in a taxi. By public transport it’ll take about an hour.

The suggested routes are:

- RER Line B to Le Bourget station, then the 152 bus (Direction: Gonesse, ZAC des Tulipes Nord) to the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace stop.

- Métro Line 7 to La Courneuve then the 152 bus (Direction: Gonesse, ZAC des Tulipes Nord) to the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace stop. (NB. Part of the La Courneuve station is under construction at moment. It’s not clear whether the Ligne 7 platform is affected.)

When I went, I caught the Métro 12 route to Porte de la Chapelle and then a 350 bus (Towards Roissypole – Aeroporte CDG) to the museum. When you come up out of the métro, you need to cross over the dual-carriageway to where the buses are located. The Musée de L’Air Et de L’Espace bus stop is only the third stop but you spend the first part of the journey on the motorway (Autoroute du Nord), so don’t be alarmed.

Entry Price (2023):

The ticketing structure is a little complex. Their “Check-in” ticket gives entry to the museum. The “Boarding Pass” grants access onto some of the aircraft – The C47, The Concordes and the Boeing 747. But the standard ticket is a “Check-in and Boarding Pass”. Prices vary according to date and age, and there are extra add-ons for things like the Planetarium, the Le Bourget Control Tower, and guided tours.

| Check-in & Boarding Pass | |

|---|---|

| Adult (26+ yrs) Before 31 Dec 2023 | € 16.00 |

| Adult (26+ yrs) From 1 Jan 2024 | € 17.00 |

| Adult (18-25 yrs) | € 8.00 |

| Youth (4-18 yrs) | € 6.00 |

| Child (under 4 yrs) | € Free |

| Extras: | |

| Planétarium | € 6.00 |

| Control Tower visit (4+ yrs) | € 4.00 |

| Guided tour | € 6.00 |

Opening Hours (2023):

The museum is open every day except Mondays:

- between 10am and 6pm from April 1st to September 30th

- between 10am and 5pm from October 1st to March 31th