The Laatzen-Hanover Aviation Museum (Laatzen-Hannover Luftfahrt Museum), to give it its full name, is not a huge museum but it’s a really interesting aviation museum and it packs a lot – some 4,000+ artefacts – into its 3,500 m² of display space.

The museum was founded by a businessman, Günter Leonhard, who was obsessed with aviation. As a young man he’d joined the air force but never got to fly. However his success with his freight forwarding company, Nelke, enabled him to build a large collection of aviation artefacts. He sold the business in 1992 and retained the warehouse in Laatzen for his new museum. His team of aviation enthusiasts also specialised if finding wrecked aircraft and restoring them. He died in October 2011.

The focus of the museum is on the development of aviation and particularly German aviation, which is a sensitive subject that I’ll explain later.

Museum Entrance

If you are reading this post anywhere other than Mechtraveller, it has been stolen.Outside the museum there are two ‘gate guardians’ to welcome you*. They look, as all aircraft exposed to the elements quickly do, slightly shabby, but they are interesting examples of the German aviation industry.

On the ground is a Dornier Do28 D-2, a versatile twin-engine propeller aircraft with Short Take-Off & Landing (STOL) capabilities developed in the mid-1960s. As a light utility aircraft, it was used mostly by the military, although there was a civilian version, and this one is painted in Medevac Red Cross colours.

On a stand above the entrance (Feature photo) is a business jet also from the mid-1960s. The HFB-320 Hansa Jet, manufactured by Hanmburg Flugzeugbau was instantly recognisable because of its forward angled main wings. This was an idea played with by aircraft designers at that time, looking for more agility in fighter aircraft. Whether or not that made it a little more ‘edgy’ to fly, is not clear but it did suffer from a number of crashes that were put down to pilot error. It also served with the German Air Force as an Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) aircraft.

The museum has two halls. The first hall covers the pioneering years of aviation up to the 1930s and is laid out more or less chronologically. The main hall covers everything from the 2nd World War, through to the Cold War ending in the early 1970s, but not really laid out chronologically; the layout seems more dependent on the display space.

The First Hall – Pioneers of Aviation

After a scale model tribute to the Montgolfier brothers hot air balloon experiments, the displays start with the man himself, German civil engineer Otto Lilienthal, widely acknowledged to be the first to fly, or at least glide successfully, multiple times. The board on the wall behind him and one of his gliders generously acknowledges the British engineer Sir George Cayley, who never got airborne himself but used models to develop the key principles of flight and its governing forces that Lilienthal and later, the Wright brothers, used.

There’s a replica of Hans Grade’s 1909 monoplane. Grade had become an aviation enthusiast aged 15 when he first heard of Lilienthal’s glider flights. Five years after the Wright brothers had made the world’s first powered flight in 1903, Grade made Germany’s first motorised flight in his triplane. A year later (1909) he designed and flew his monoplane winning a prize for the first flight by a German aeroplane with a German engine to fly a loop between two pylons a kilometre apart. Another year later he set up the first flying school in Germany.

Then came World War I, and aircraft were armed for war. As usual the pressing urgency of war speeds up research and innovation, as highlighted by the 1915 Fokker Eindecker EIII which was the first purpose-built German fighter aircraft and the first aircraft to be fitted with a synchronization mechanism so that the single machine gun could fire through the arc of the propeller without hitting the blades. Suspended above the Eindecker is a replica of the French Nieuport 17 which entered service with the Allies a year later in 1916 with a single Lewis machine gun mounted on the top wing that had to be reloaded in the air by the pilot. Clearly the Eindecker’s synchronised gun system was superior and before long the Nieuport was refitted with synchronised guns… except by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) for some reason.

Before long the arms race had created a range of sophisticated aircraft including the Fokker Dr.I triplane (made famous by Baron von Richthofen) and the British Sopwith Camel. The museum has replicas of both.

It also has a section of the real thing – the restored tail plane of a German 2-seater Halberstadt CL IV reconnaissance aircraft. It is of interest to avgeeks because it’s the first example of printed camouflage on the tail plane, and on the rudder it displays a simple straight ‘Iron Cross’ called the “Balkenkreuz”. German military aircraft before this used the old curved edge cross. The Balkenkreuz stayed to the end of World War II and then, when the German air force was reconstituted, they returned to using the old cross (see the marking on the F-104 Starfighter below).

As soon as World War I ended, the development of civil aircraft restarted, and the museum have an example of a Junkers 13 A. Designed in 1919 and making ground-breaking use of corrugated aluminium, this was one of the first purpose-built commercial transport aircraft. It could carry four passengers in a heated cabin, and two pilots, for 650 nautical miles at 5,000 metres. It was so successful it was sold all over the world despite restrictions imposed by the Versailles Treaty on Germany after the war. That design can easily be recognised as the forerunner to the Junkers 52, of which more in a minute.

At the end of the Hall 1 gallery, there are a number of interesting , unusual or rare aircraft.

The 1922 Rieseler RIII 22 sports plane was built to comply with the Versailles Treaty. With a maximum take off weight of just 338 kg, we’d call it a microlight (max 500 kg) these days. Their test pilot happened to “accidently” land one of these on Berlin’s main street, Unter der Linden, in July 1923, just when, by extraordinary coincidence, there were an unusual number of press photographers in the vicinity…. naturally sales shot up!

Suspended above the Rieseler is an 80th scale model of Charles Lindburgh’s ‘Spirit of St. Louis‘, and on the floor a Focke-Wulf Fw 44 – Stieglitz (Goldfinch) biplane. This aircraft was designed in 1932 to be a two-seat trainer, by the legendary engineer, Kurt Tank, who went on to design the Fw-190 and the Fw-200 Condor. It was a successful aircraft that was built under license in 5 countries and sold to 14 others.

Close by is the fuselage of a rare Rhein Flugzeugbau (‘Rheinflug’) RW-3 Multoplan. Chronologically it should be in the next hall because the 2-seat light aircraft was designed in 1955. What makes it unusual is its propulsion. It is a single-engine pusher aircraft, with the engine mounted in the fuselage behind the cockpit and the pusher propeller mounted between the fin and rudder. Not many were made.

Above flies a Belgian two-seat trainer/tourer biplane designed and built by Stampe et Vertongen in Antwerp. Only 35 were built between 1933 and the start of WW2 when the factory was closed. It reopened and started producing the SV-4c for the Belgian and French air forces. They are still being flown by private owners today.

All along the back wall of the viewing platform in Hall 1, are displays of artefact, equipment, document, photographs and scale models. The museum has over 600 high quality scale models and dioramas, two thirds of which are 1:72 scale. It’s a good way to make up for not having more space for life size aircraft.

The Main Hall

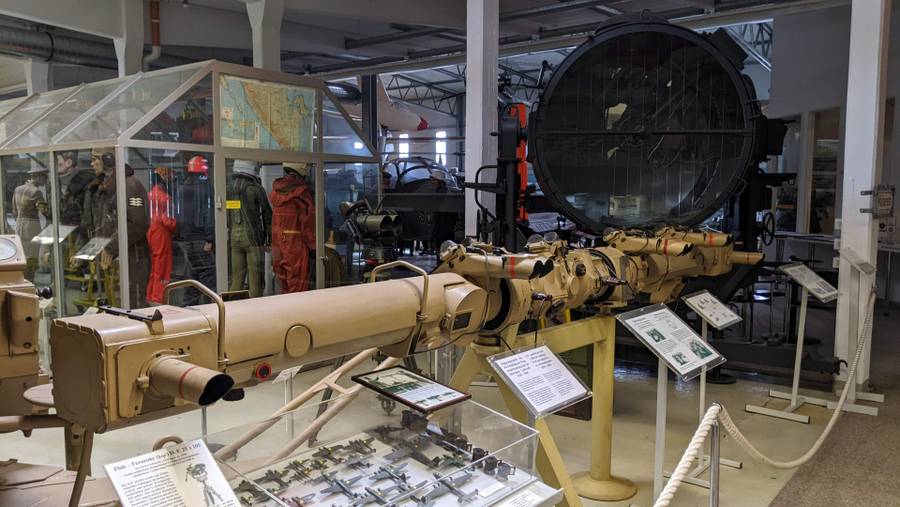

As well as general artefacts such as uniforms and equipment, the main hall also uses its wall space for model and artefact display cases.

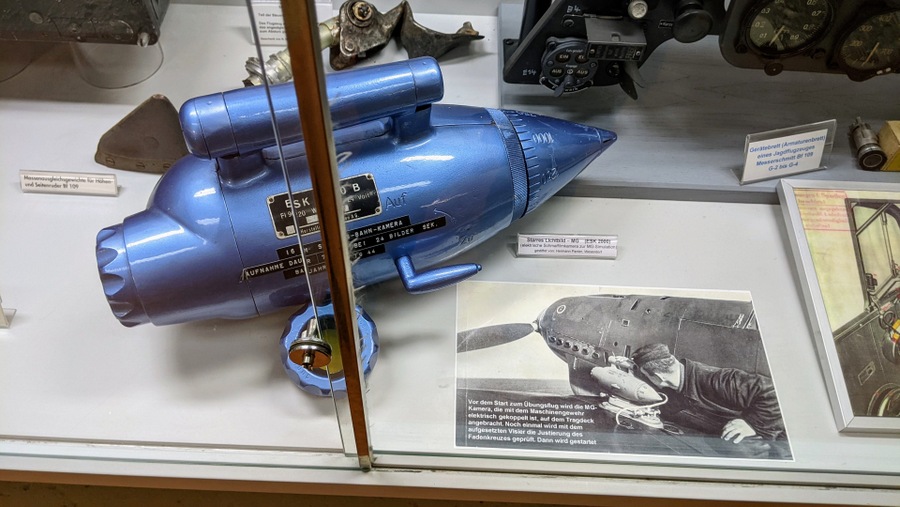

Two models in particular caught my attention because they opened up stories about which I knew nothing (and if you are a regular reader you’ll know it’s always the rare, unexpected or unknown exhibits that excite me).

Lufthansa Catapult Ships

How’s this then? A model of one of Lufthansa’s catapult ships, the Ostmark.

In the 1930s aircraft were beginning to muscle in on the lucrative intercontinental mail services which had been the preserve of shipping for the last two centuries – after all, mail was all about speed of delivery, and aircraft, as Charles Lindbergh had demonstrated in 1927, were beginning to have the range needed.

Deutsche Lufthansa got going on the Europe to South America transatlantic route. They bought two merchant ships and converted them into catapult ships. Later they would build two more, purpose designed, ships, one of which was the Ostmark.

The routine was that the mail was flown first to Seville, Las Palmas, or Bathurst (Gambia). It was then transferred onto a flying boat, which would fly to meet its catapult ship in the Azores or Canary Islands. Once it had landed it would taxi to the catapult ship’s floating mat (for stability) and be lifted on board by crane where the mail was transferred to another seaplane which was waiting fully-fuelled on the catapult. The catapult saved the seaplanes from using valuable fuel taking off from water. The ongoing aircraft took the mail to Natal, Brazil. When they started the service in 1934 it was twice monthly but it soon became weekly, and mail would take just four days to get from Berlin to Natal.

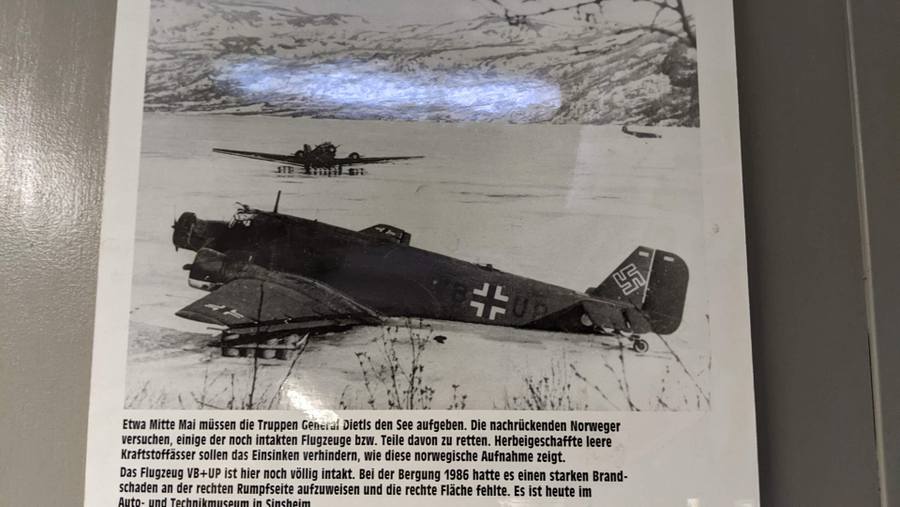

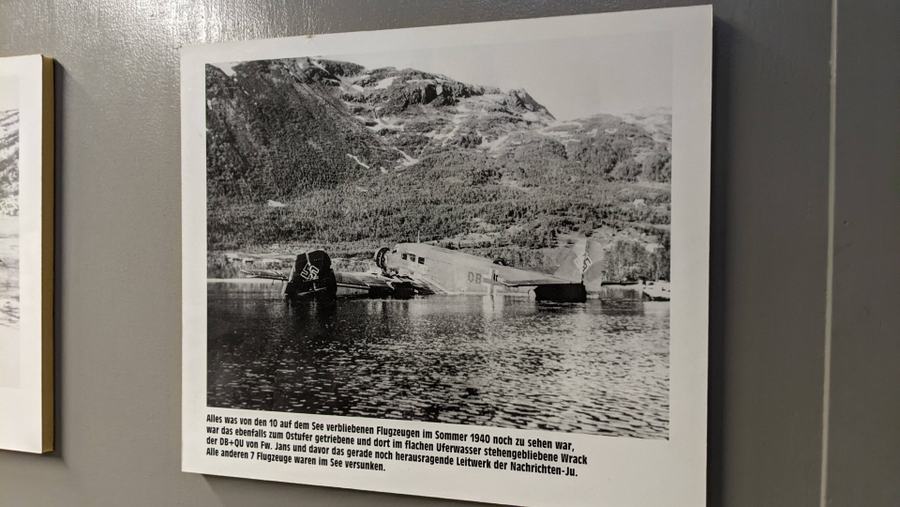

Ju 52s in Lake Hartvik

The second model that caught my eye was of a large frozen lake, with 13 x Junkers 52s on it.

I had never heard of this event, but it turns out to have been a bit of a shambles for the Luftwaffe.

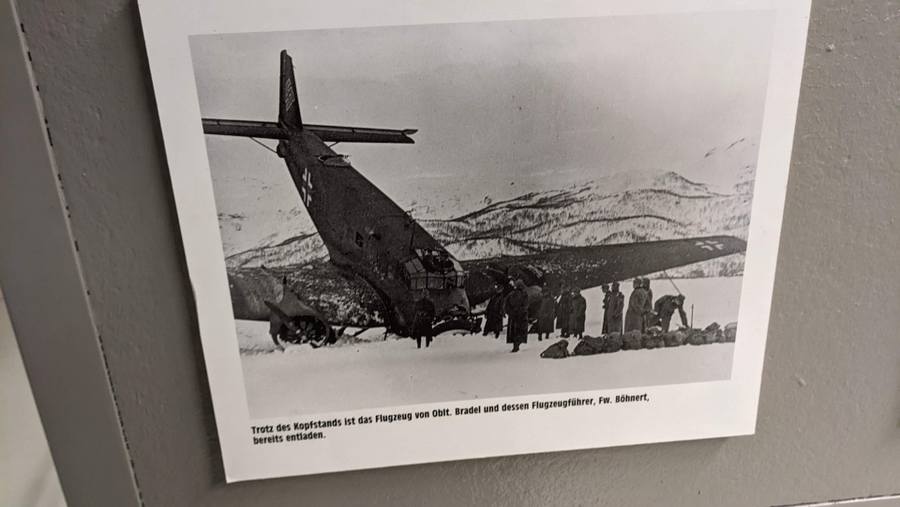

During the German invasion of Norway in spring 1940, the Allies and Norwegians put up stiff resistance at sea and on land around Narvik. The Luftwaffe were brought in to help re-supply the German forces. Thirteen Junkers Ju-52s were used to deliver artillery, supplies, ammunition and troops from Berlin on 13 April 1940. They decided to use the frozen ‘Hartvikvatnet’ (Lake Hartvik)’, 10 miles outside Narvik, as their airfield. Two of the aircraft never made it. They got lost and ended up on a different lake 45 miles away where they came under air attack the next day and were destroyed. The remaining aircraft landed on Lake Hartvik, but several were damaged when they hit an unexpected covering of thick snow & slush, which also prevented the remainder from taking off again. They were becoming trapped and the situation was exacerbated by a shortage of fuel and Allied air attacks that took place over the next two days. Finally just one aircraft managed to take off and make the short hop to neutral Sweden where it was interned.

So, a total loss! In the spring thaw, the remaining ten aircraft sank to the bottom of the lake. Thirteen turned out to be an unlucky number for the Luftwaffe.

But the story doesn’t end there. In 1986 the museum’s founder Günter Leonhard led an expedition to the lake to find them and if possible, recover some. In a laborious 18-year salvage operation, they managed to pull four Ju 52s from the water – the last one surfacing in 2004.

“When after 46 years,” he later told a newspaper, “the first machine came up from a depth of 72 meters, I had palpitations – that was the greatest experience of my life.”

There is a small section of one of those Ju-52s in the museum, but the building is just not big enough to house a fully restored Ju-52, which is what the museum’s team of restorers have done. That aircraft is now housed 35 kilometres away at the associated Ju52-Halle museum next to Wunstorf Air Force Base.

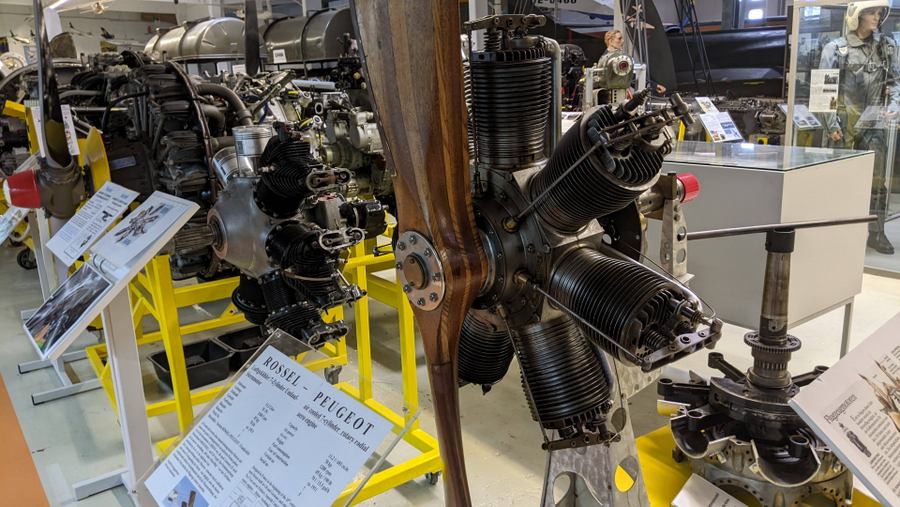

Aero Engines Display

In addition to equipment, uniforms, and aircraft in this hall, there is a collection of important aircraft engines, some of them extremely rare, like the Junkers Jumo 004 A turbojet that powered the legendary Messerschmitt Me-262.

This engine is from the A series, the prototypes used mainly for testing, which is what makes it rare. The B series were the production models.

The engine collection starts, at least chronologically with a Rossel-Peugeot 7-cylinder 70 hp rotary radial engine. These engines were designed almost as soon as aviation began, and first appeared in 1907 – 4 years after the Wright brothers flight. It was so new, the French car manufacturer, Frédéric Rossel who had persuaded the Peugeot brothers to create an aviation startup venture with him, couldn’t actually find an aeroplane to test it on! They ended up having to spend 3 years building their own aircraft. This engine was made in 1910. The engine design was released under licence to several manufacturers, and so the engine and its siblings ended up opposing each other during WW1 in Fokkers, Sopwith Camels and Nieuports.

The Junkers Jumo 205 diesel engine is presented as a cutaway. It’s not an engine I’d ever given much thought to. It’s design goes back to 1932 when Lufthansa were looking for a reliable and economic engine for their long distance seaplanes… remember the catapult ship earlier? This 6-cylinder, 2-stroke diesel produced 880hp and the low fuel consumption they needed. An interesting side note: the military were not interested in it – diesels are not responsive enough to the sudden and frequent changes to rpm, that fighters & bombers demand.

I had not heard of the Argus As 410, a 600hp V6 engine produced by Argus Motorenbau in Berlin. It was produced from 1938 to 1945, and then after the war was made in large numbers by the French SNECMA company. It had an unusually efficient air-cooling system and it powered some of the Luftwaffe’s less well known aircraft like the Arado AR-96 advanced trainer, Focke-Wulf Fw 189, Henschel Hs 129A, Siebel Si 204 transport aircraft… and the Argus Fernfeuer.

Wait! What? The Argus Fernfeuer was a proposal made in 1939 for an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for mine-laying, torpedo bombing, bombing and reconnaissance. By 1941 the project had been dropped in favour of another unmanned bomb, the V1.

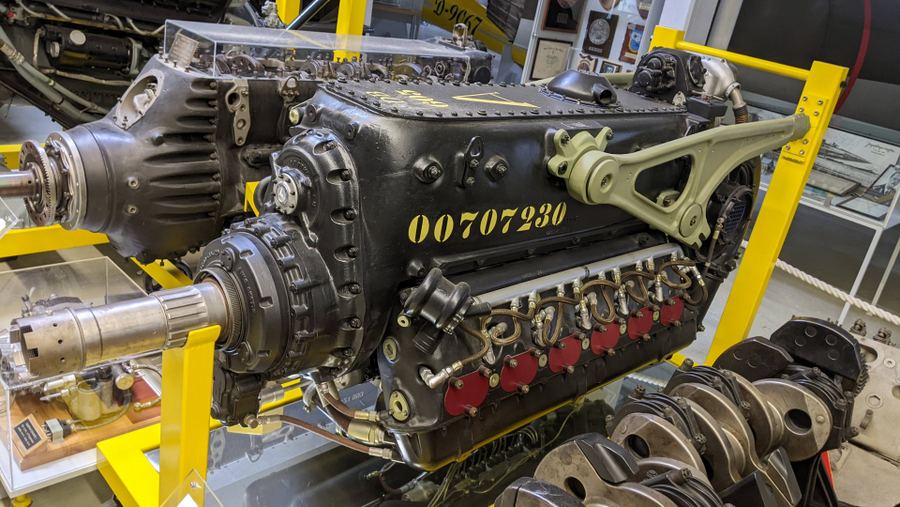

Then come some of the better known engines of WW2…

- The Rolls Royce Merlin, fitted to Hurricanes, Spitfires, Lancasters, Halifaxes, Mosquitos. It started out at around 1,000hp and by the end of the war Spitfires and American Mustangs were whizzing about at high altitude with a 2-stage supercharger version churning out over 2,000hp.

- The two main iterations of the powerful Daimler Benz fuel-injected engines (that would humiliate early Spitfires by not cutting out in negative G manoeuvers)

- The 1,075 hp DB-601 was fitted to Messerschmitt Bf-110, Bf-109 E & F models, the Heinkel He-100. 19,000 of these were built in Germany and also under license in Italy & Japan where they powered the Machi 202 & Kawasaki Ki-61.

- And its successor the 1,475hp DB-605 fitted to ME-109 G & K models. These two engines were also made under licence in Italy for the Fiat 55 and Macchi 205

- And the Junkers Jumo 213 engine, an upgrade on the Jumo 211 which powered the Ju-87 (Stuka), Ju-88 and Heinkel 111 bombers, now with a 2-stage supercharger producing 1,750hp and taking Ju-88s, Focke-Wulf FW-90 Ds and TA-152s to greater heights at greater speeds.

Speaking of horsepower, the museum does have another engine on display over on the other side of the hall. It’s the mighty Napier Sabre III. In terms of horsepower, its early variants started with 2,200 hp (more than the Db 601/5 or Merlin ended with) and finished up at 3,500hp! This particular engine is awaiting restoration, which is why it isn’t displayed with the other engines. It comes from a Hawker Tempest that was shot down by AA fire near Stade in Northern Germany in April 1945.

Moving into the jet era, there’s the aforementioned Junkers Jumo turbojet, then a Klimov VK-1 RD-45 centrifugal flow turbojet. Now this was based on the latest development of Sir Frank Whittle’s first turbojet designs, which was the Rolls Royce Neme engine. Much to the Americans’ annoyance, they were exported and licensed to the Soviet Union in 1947. The Americans were right to be annoyed because the next time they saw these jet engines they were inside the revolutionary Mig 15s in the skies over Korea!

The aircraft

The largest aircraft in the museum is the amazing Soviet Antonov An-2, designed in 1947 to be a rugged and reliable transport aircraft, crop-sprayer, fire-fighter, ambulance… and anything else a high-lift utility aircraft could be used for. It was produced in big numbers (18,000+), especially in its 12-seat passenger variant, and was still being produced in 2001! I remember seeing dozens and dozens of them littering the airport at Odessa in 1994.

Next to the Antonov is another Soviet post-WW2 aircraft, the Yakovlev Yak-18U trainer, designed in 1946. Again, produced in large numbers (11,000), this military trainer was exported and licensed to almost 30 Eastern bloc and USSR-friendly countries.

And the Museum’s third high volume (17,300) Soviet aircraft is the famous Mikoyan-Gurevich MIG-15, using the Klimov engine mentioned above. It’s good that they have it, but these days, rather like Enigma code machines, it’s hard to find a museum that doesn’t have one!

Opposite the MIG is an exciting sight; the 5-bladed, clipped wing, Supermarine Mk XIV Spitfire.

The Mk XIV was one of the more numerous of the later Spitfire variants – 957 were built. It had a 2,050hp Rolls Royce Griffon engine with a 2-stage supercharger. This aircraft, restored by the museum, is one of around ten examples still flying or on static display, and the only one in a German museum. It is displayed in a little tableau setting of an RAF airfield, with pilots, ground crew and an MG sports car.

Next to the Spitfire are two of the museum’s most important and impressive restorations…

A Messerschmitt Bf 109G-2. The G (‘Gustav’) variant was powered by the new DB-605 engine and was a significant upgrade. This aircraft however didn’t last long. It was shot down over Sardinia in 1943 (the pilot survived but was shot down & killed a year later) and fished out of the Mediterranean by the museum in 1988.

A Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A-8

The A-8 variants were produced from Feb 1944. This one (below) is a new-build/restoration hybrid – a mongrel! It was the first prototype for a set of new-build FW-190s being built in 1996 by Flug Werk GmbH at Gammelsdorf, based on original plans and some original parts. It was the test bed before 16 airworthy FW-190 A8s were built. It was bought by Gunter Leonhardt and completed using parts from seven wrecked aircraft including one pulled out of the nearby Cheiner marshes outside Salzwedel in Saxony-Anhalt in 1997, and it was put on display in the museum in 2006.

The three most modern aircraft in the museum include the only helicopter.

The reason the French Sud Aviation/Aerospatiale Alouette II appears in the collection is that its roots lie in German expertise. After WW2, Prof Heinrich Focke and his colleagues, who had pioneered the development of helicopters in Germany, in particular the twin-rotor Focke-Wulf Fw-61, were hired by Sud Aviation in France. They designed the Alouette I with a piston engine, then in 1955 Sud Aviation introduced the turbojet-powered Alouette II, which was hugely successful and sold around the world. This Alouette II came from the German Army helicopter training unit in Bückeburg.

The 1953 Italian 4/5-seater Piaggio P-149D utility/liaison/trainer, also has a German connection. The D variant was made by Focke-Wulf under license and the Lycoming engines were made under license by BMW. The Federal German Air Force bought 72 from Piaggio and a further 190 from Focke-Wulf to be used mostly as trainers between 1957 – 1990.

Probably the most glamorous aircraft in the hall, is the Lockheed F-104G Starfighter. The Mach 2 interceptor became the mainstay of West German Cold War air defences. Always on high alert, they even attached rockets to them so they could be instantly launched into the air. The downside was that they could be notoriously skittish in the air and the West German pilots had more than their fair share of accidents in them. They became known as “widow-makers”.

Here’s something I hadn’t seen before. The Starfighters had an emergency Auxiliary Power Unit (APU), which the pilot could pop out to generate power to restart the engine in a flame-out situation.

One of the museum guides (ex air force, I think) told me he had seen or known of a Starfighter pilot manage to use it twice as he plummeted to earth, to get his engine re-started. He survived.

Passion

I realise that what makes this museum special is passion. Driven by its founder, Günter Leonhard, the museum has had to battle with two hardships in particular…

1) After both the First & Second World Wars very few German aircraft or equipment were left intact, and those that were were snapped up by the victors to be studied or as war reparations. Most German military aircraft are in foreign museums.

There is still a stigma.2) There is still a stigma. One of the volunteers was quoted ¹ in a local newspaper a few years ago: “We’re a taboo that you don’t want to go to. When we approach foundations [for support], they don’t want anything to do with us. Because there is a “shadow” that lies over the museum. And it’s some exhibits that cast that shadow. Some of the historic aircraft were developed as war machines and equipped with machine guns or bombs. Other exhibits bear symbols such as the swastika, the star of the Soviet Union, the hammer and sickle of the communists or the emblem of the GDR. They are machines built to kill and symbols of war.”

It’s true. For example, the swastika is a banned symbol in Germany for obvious reasons. You can display swastikas for historical purposes if you have official permission to do so. This means swastikas can be displayed on museum aircraft on static display, but reportedly not on airworthy aircraft unless part of a historic flight** .

So, over the last thirty years, Günter Leonhard, and his volunteers worked tirelessly to source artefacts that are sensitive for some parts of the population, and to find rare aircraft, some as wrecks which they have lovingly restored. They have created an amazing collection with absolutely no funding from outside agencies, the state, or the federal government. Their only income has been from entrance fees, membership fees for the museum association, and donations.

It’s a great shame there hasn’t been more support, because the museum draws visitors from all over the world but proportionately not so many from Germany. Since the museum’s mission is to show German aviation prowess and its place in the global development of aviation, today’s generation of Germans are the audience it wants to reach. We foreigners all know what a key role the extraordinary engineers, designers, and aviators of Germany have played in the development of aviation. Wouldn’t it be good if Germans themselves could feel more pride in their achievements?

And if the museum’s dogged determination to promote Germany’s aviation history isn’t a sign of real passion, here’s another that I noticed. Many small aviation museums are run on a shoestring, and struggle to keep their artefacts in top condition and laid out well, especially when there’s a lack of space. The Laatzen-Hannover Aviation Museum is spotless! No dust. No broken bits. Nothing looking shabby (except the weathered aircraft outside) and there’s space to move around objects. Honestly, you could eat your lunch off the floor, and I’m not sure I’d try that at the RAF Museum or IWM Duxford!

It’s as if they are saying “we are going to show off German aviation excellence, even if unloved by some, and we’re going to do it properly!”

…Passion.

* The museum has one other gate guardian-tyle aircraft. A few hundred metres away on a main road next to the Hanover Messe (Exhibition Centre), a Soviet MiG-21F-13 Fishbed-C flies at a dramatic angle, high up on a metal stand, to advertise the museum.

** Which must apply to the reproduction ME-262 jet that flew this week in the RIAT air show and is normally based in Manching, Bavaria.

¹ Friedrich-Wilhelm Korff, a former professor of philosophy at Leibniz Universität Hannover in Hannover Allgemeine 04/12/2018 .

NB: If you are reading this post anywhere other than on Mechtraveller.com, it has been stolen. You should exit immediately.

Declaration: I was on a press trip in the region as a guest of the 9 Cities of Lower Saxony and Visit Hannover. Museum entry was complementary.

Factbox

Website:

Luftfahrtmuseum Laatzen-Hannover

Getting there:

Ulmer Straße 2

30880 Laatzen

Germany

The museum is just one block away from the Hanover-Laatzen Convention centre.

Entry Price:

| Adult | € 10.00 |

| Child (over 5), student | € 5.00 |

| Family (2 adults & 2 children up to 15 yrs) | € 25.00 |

| Groups (from 15 persons) | € 8.00 each |

Guided tours are available (Adults: € 50, Children up to 14 years: €30)

Opening Hours:

The museum is open from 10.00am – 17.00pm (last entry 16.00pm) year round on Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays. (Check for public holidays).