The clock museum, or ‘Musée de l’Horlogerie’, in Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont presents a really interesting social and industrial account of the rise and partial decline of a town focused on a single technology.

Back in the 1950/60s, Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont was renowned in France as a centre of light engineering, particularly clocks. Practically everyone in France woke up to the sound of a Bayard alarm clock, and counted away the hours in the office, workshop, kitchen or shop on a Bayard wall clock. Bayard was the town’s biggest employer and their clocks – alarm clocks in particular – were exported all over the world.

As well as recounting the history of the town’s foremost industry, the museum also looks at the working lives of clock-makers, apprentices and ordinary workers. As an example, they reproduce the Bayard production line of the 1960s when everything was still assembled by hand, to illustrate the workers’ experience.

The birth of clock-making in Saint-Nicolas d’Aliermont

The 60s & 70s were the peak years, but it all began back in 1725 with the arrival of Charles-Antoine Croutte, the first clock-maker to settle down in Saint-Nicolas d’Aliermont. Charles-Antoine was the son of a clock-maker in Dieppe, and he in turn had 12 children who became the foundation of the clock-making dynasty in Saint-Nicolas.

Clock-making was a cutting edge technical skill in the 18th century, so naturally it attracted young apprentices from the region, eager to learn from Croutte and be in on the latest tech. By 1750 there were eight workshops (‘startups’ we’d call them today) in the town, manufacturing components for watches & clocks. By 1789 there were twenty.

The town quickly became known for its style of clock. We might think of them as simply ‘Grandfather Clocks’ but these 17th & 18th century tall case clocks with elegant faces and intricate wooden cases were known as ‘Saint Nicolas Clocks’. The estimate is that around 10,000 ‘Saint Nicolas’ clocks were made. There are around 3,000 still in existence.

In 1807 another well-known watchmaker, Pierre-César Honoré Pons, came to Saint Nicolas.

Pons had trained with Antide Janvier and by 1803 had set up as a clockmaker in the rue de la Huchette in Paris, not far from the Place Saint-Michel where the great watchmakers such as Berthoud, Breguet and Lépine worked. By the time he came to Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont he was well-known for his mantelpiece clock mechanisms. His, completely over-the-top, Galileo clock featuring the astronomer holding a tablet illustrating Copernican heliocentrism (which he championed) is a typical example of his enthusiasm!

He also pioneered the mechanisms and style of carriage clocks, for which the town soon became famous.

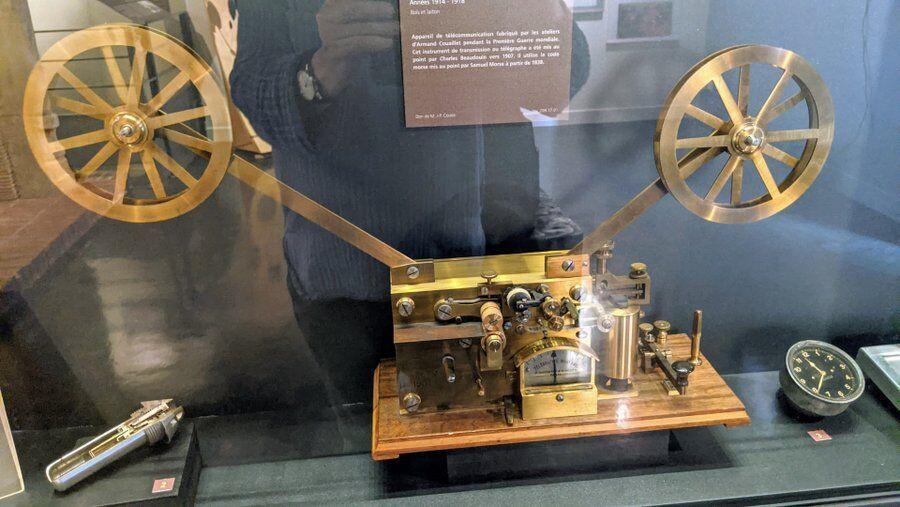

His arrival triggered another wave of start ups and creativity through the 19th century. These included the marine chronometer manufacturers Aimé Jacob, Victor Gannery and Onésime Dumas, the clock manufacturer Armand Couaillet and the watchmakers Villon, Duverdrey and Bloquel, who were to become the future founders of the Réveils Bayard brand.

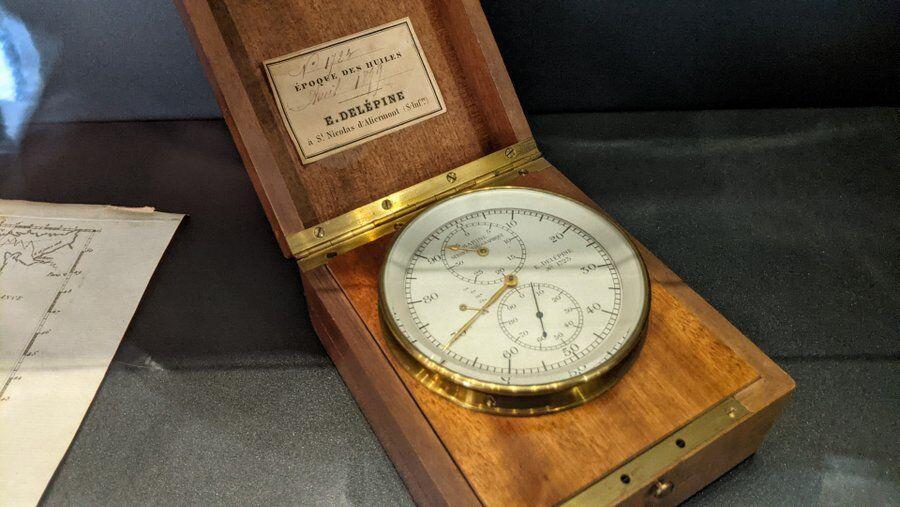

In 1846, when his health was declining, Pons sold his workshops to the watchmaker Delépine. When he died he left a fund of 1,000 francs to support clockmakers who fall on hard times.

Marine chronometers were a specialised branch of the industry. Used to calculate longitude, by keeping the time at a vessels departure point (or a point like Greenwich or Paris) and comparing it with ‘local’ time (from observing the sun’s zenith at noon), a chronometer has to be highly reliable and highly accurate in changing conditions; varying temperatures, varying humidity, varying atmospheric pressures, and varying sea conditions… not to mention salt corrosion! The English clock-maker John Harrison had led the way in 1736 and now other clock-makers were following his lead, and trying to improve on his designs. Once again, Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont became well-known for its marine chronometer production.

Albert Villon established his clock making shop in 1867 in Saint Nicolas. He specialized in marine clocks and carriage clocks. He then partnered with Paul Duverdrey and Joseph Bloquel to make many types of clocks, including traditional carriage clocks with solid brass cases and bevelled glass fronts, sides and backs and visible escapements.

advertising poster

for Bayard

In 1902 Duverdrey & Bloquel succeeded Villon. It was they who changed the name to Bayard and steered the company into the mass production of alarm-clocks. The Bayard brand was famous in France and abroad in the 1920s. The factory employed up to 990 men and women from the village and the surrounding area. Decades later, in 1978 Bayard was taken over by Jaeger-Levallois from Switzerland.

Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont begins to diversify

The First World War marked another turning point in the industrial history of the town. The watch industry becomes a strategic asset in time of war because it can easily switch to produce the precision mechanics needed for armaments. Shell fuses, ammunition and communication devices (telegraphs) were produced in large numbers at Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont between 1914 and 1918.

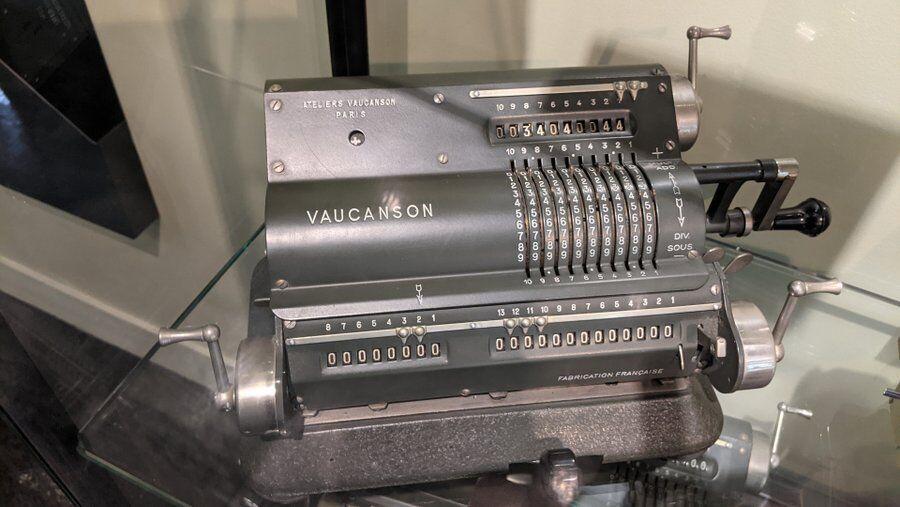

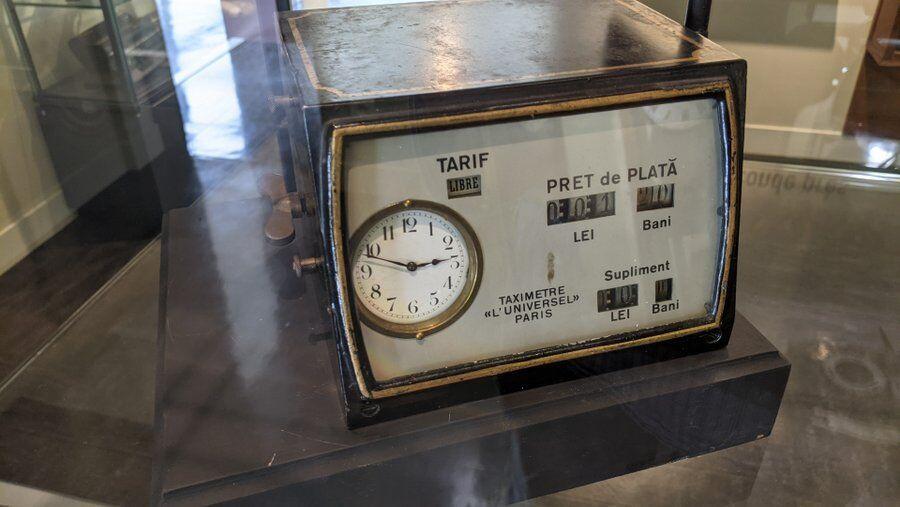

When the war ended, the watch factories continued their diversification into light and precision engineering. The range of products emanating from Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont blossomed, as can be seen on display in the Clock Museum. The town produced everything from typewriters to scientific instruments, from calculators to speedometers.

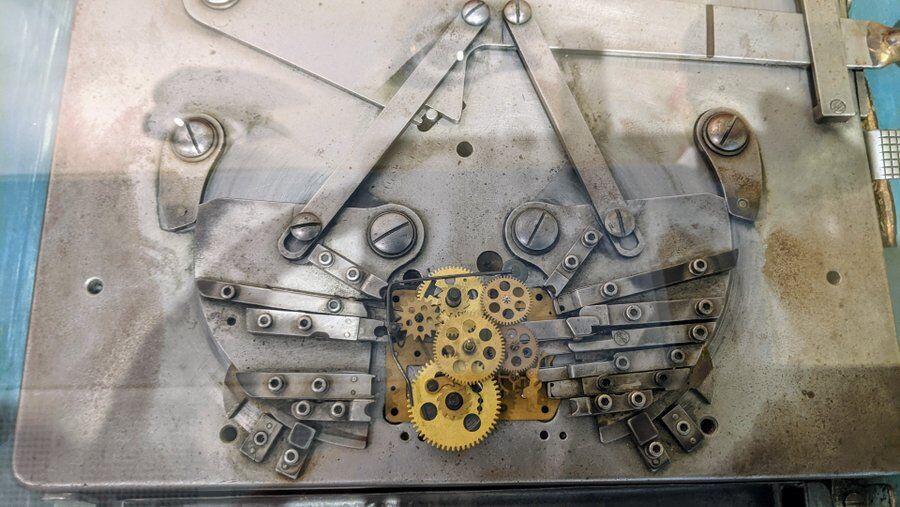

One of the leading companies in the drive to diversify was Ateliers Vaucanson, who took over Lamazière & Bunzli in 1914. Lamazière & Bunzli specialised in making Flaman System recorders for SNCF (national railways). Flaman recorders were invented by a railway engineer, Eugène Flaman. They recorded time, distance and speed on a route. Vaucanson continued with the recorders but also added other products including parts for the automobile industry and equipment for the movie industry. Vaucanson in turn were bought in 1955 by the Danish firm Ericsson who manufactured telephone sets.

The decline of the clock-makers of Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont

The tide began to turn in the 1970s & 80s as electronics took over many of the complex mechanical functions that the town’s factories and workshops were famous for. For example, over three generations the Denis family tried hard to keep up with the times. The son of a traditional watchmaker, Gustav Denis, set up Denis Bros (Denis Freres) to produce miniature counters and timers on an industrial scale. Then between 1942 and the 1960s they focused on manufacturing toy cars and watches.

In the 1950s Gustav’s great-grandsons begin to follow new opportunities. In 1958 they set up a plastic injection-moulding workshop and start making components for the automobile industry, the railways and electronics manufacturers. In the 1970s they pivoted again and began making high precision mechanical components for the military and civil aeronautical industry, earning the stamp of approval from NASA and NATO (they made engine parts for Mirage jets).

In 1975 they switched their attention to electronics and their 120 workers began making intercoms, but soon after they were bought out by another company and set to making thermostats and gas taps. Sadly, due to falling orders it finally closed its doors in December 1991.

If a company as agile as Denis Bros couldn’t stay in business, it’s no surprise that many of the great manufacturing ‘names’ of Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont disappeared in the later stages of the 20th century.

There are still a few light engineering firms in the town, but if you take a drive around the streets you’ll see the former sites & buildings – some in Art Deco style – of the old factories now closed, abandoned, or repurposed.

On a personal note, I am struck by the story of Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont’s growth and decline.

My father founded a light engineering company in the 1930s. They made electrical meters. Very good ones. They were the premier brand in the 1960s to 1980s. Like Denis Bros, in the early 80s they diversified by re-allocating a redundant moulding press to turning out knobs. I ended up ‘broadcasting to the nation’ on a radio studio mixing desk twiddling my father’s knobs (yeah, I know! I did just say that!) while watching his meters.

BUT digital came and analogue declined.

Fortunately my dad had always invested in university research, and one of those projects – fibre optics – came good. The company, already high-precision engineers, started making the ‘fishplates and sleepers’ (building bricks for railways) for the rapidly expanding Fibre Optic industry; IE connecters and beam splitters. When the company was sold in the 1990s, it was into a growing market.

Declaration: I was travelling through France on a self-driving trip. I honestly can’t remember if I paid to get in or produced my press card and got in for free. Assume the latter.

Factbox

Website:

Musée de l’Horlogerie

The museum also has an online audio guide in English. You can listen to it ‘live’ on your phone, or download it in advance.

Getting there:

Musée de l’Horlogerie

48 Rue Edouard Cannevel

76510 Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont

France

It’s on the main road (D56) that passes through Saint Nicolas. Easy to find!

Entry Price:

| Adult | € 5.00 |

| Students, unemployed, disabled, OAPs | € 2.50 |

| Groups (10+) | € 3.00 each |

| Under 18s | Free |

Opening Hours:

High Season: 1 June to 30 September

Tue-Sat 10am – noon & 2pm – 6pm

Sun 2pm – 6pm

Low Season: 1 October to 31 December and from 15 February to 31 May

Wed – Sun 2:30pm – 6pm

The museum is closed from 1 January to 14 February, on 1 May, 1 November, 11 November and 25 December.