The Battle of Agincourt Museum, or le ‘Centre Azincourt 1415’ as it is officially named, was redesigned, expanded and improved, a couple of years ago. It is now a centre of discovery and learning for all age groups with a mission to explain the background and events of October 1415 in as much detail as you want to absorb or have time for.

Of course, after its inauguration in August 2019, the museum had barely eight months to show off its new design and displays before going into lockdown. It re-opened to the public at the end of May, and hopefully it won’t be too long before restrictions are fully lifted and we non-Europeans will be able to visit easily.

Agincourt – The history

The Battle of Agincourt marked the second high point of English fortunes in The Hundred Years’ War; a collection of bloody skirmishes and battles between England and France competing for the French crown between 1337–1453 – so actually 116 years.

What started as a dispute over Gascony between Edward III of England and Philip VI of France, got off to a flying start for the English who dominated the Channel, took Caen (Normandy) and defeated Philip’s army at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, before heading up the coast to siege and take Calais the following year.

Then there was a brief pause in hostilities while the Black Death (COVID on steroids!) took its toll (75–200 million), before Edward’s son, the Black Prince, started rampaging through central & south France, and routing the French army again at the Battle of Poitiers (1356) where he took King John II of France prisoner – the first ‘high point’.

However, over the next two decades the French slowly began to win back most of the English territories in France leaving only a few towns & cities.

In 1413 Henry V was crowned King of England and launched a new assault of France two years later, on 14th Aug 1415 at the port of Harfleur.

The town put up strong resistance and finally surrendered in late September. The delay had cost Henry momentum and men. His army was now reduced to somewhere between 6,000¹ to 9,000, the majority of whom were archers… and French forces were stirring. It was clear by the beginning of October that Henry could no longer march inland to Paris. He should move north to the English port of Calais and return home to regroup.

He set off quickly but the French were quicker. By 12 October, advanced forces under Boucicault, Marshal of France, and Constable Charles d’Albret, reached the north bank of the river Somme at the first crossing point near the coast and forced Henry’s army to turn inland along the south bank of the river towards the main French forces who were gathering at Péronne.

Eventually, on 19 October, Henry found a relatively uncontested crossing point at Voyennes and finally his tired, hungry and dispirited army (there were rumours that the French numbered 100,000 men) headed for Calais again.

However, the French forces were able to intercept Henry en route between the small villages of Tramecourt and Azincourt (Agincourt).

Agincourt – The battle

The French forces, which probably numbered 12,000 plus, were not led by King Charles VI who suffered from psychotic illnesses, or the Dauphin. They were dissuaded by the king’s uncle, the Duke of Berry who had fought at Poitiers and witnessed the capture of Charles’ grandfather. Instead they appointed d’Albret as commander-in-chief.

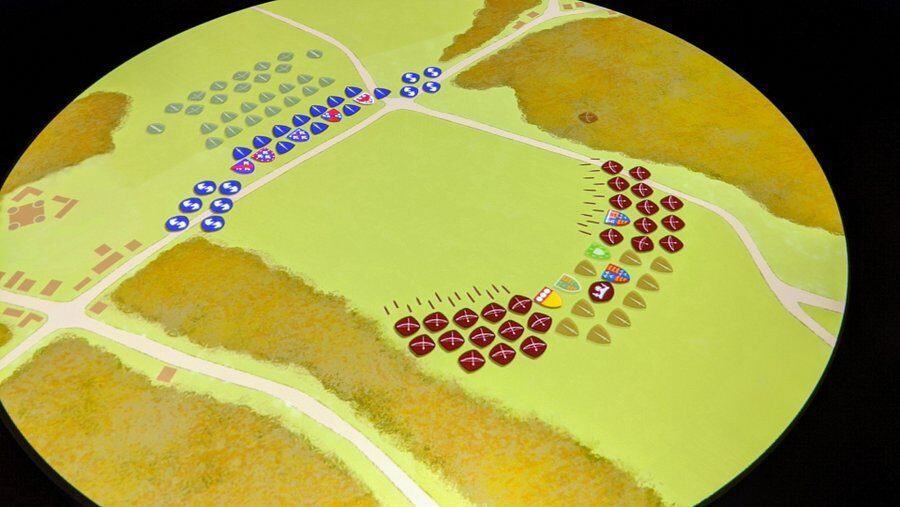

On the morning of 25th October, d’Albret began setting out his forces across the wide part of the battlefield (¾ mile¹). Henry was not overly concerned. He was probably thinking what Rod Steiger playing Napoleon in the 1970 movie ‘Waterloo’ says: “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake”!

The classic ‘mistake’ was that the ground between the French & English armies narrowed to ½ mile between the woods of Tramecourt & Agincourt. As they advanced, the French men at arms & noblemen on foot & horseback would be squeezed into a funnel. The English, on the other hand, with a smaller army, fitted the narrowed space. The English were nearly all on foot, and were comprised mostly of deadly longbow archers.

It gets worse. For the past few days it had been raining heavily. The un-trampled ground might have looked ok at first, but it was sodden and under the weight of armoured cavalry & soldiers it would quickly turn into a mudbath.

The battle was slow to start. Despite the excited enthusiasm of the young French noblemen who were confident of their success, d’Albret managed to restrain them from rushing headlong at the bedraggled English. He hoped that Henry would recognise the mis-match in forces and surrender without a fight. Henry though, was eager to get the French to attack and draw them into the trap. He thought they would attack shortly after dawn and he didn’t want let the ground dry. It was now 11.00am and nothing had happened. So he advanced the army to within 300 yds of the French – bow shot range – and opened fire. That did the trick.

The mounted men-at-arms on the French flank charged, followed by the men-at-arms on foot. As the dense cloud of armour-piercing arrows fell on them and their horses, the mudbath became a bloodbath. The horses went wild, throwing those riders who were not already wounded to the ground and knocking over or trampling those on foot. The bodies began to literally pile up as the first and subsequent rows of foot soldiers arrived on scene. Men still standing, pressed in close to each other couldn’t raise or swing their weapons.

A suit of armour weighed around 50-60 lbs. (22-27 kg). Flaying around in the mud, soldiers became quickly exhausted. Once knocked over, an armoured foot soldier could barely get back to his feet (there were no pages to help them), before being knocked down again and have somebody fall on top. The pile of French bodies stacked 3-4 high, and in among them leapt agile, bare-footed English archers, smashing them back down with axes, swords, billhooks and any weapon that came to hand. They killed many, but hundreds of the French dead were crushed, drowned or suffocated.

It was a shattering defeat for the French.

Agincourt – The museum

The exhibition space starts with a moving tableau (feature image); a recreation of the battleground with discarded armour, broken weapons and tattered banners, overlaid with the names of the French noblemen killed.

There are many history books with exaggerated numbers of the French dead, says Christophe Gillot, Director of the Centre, as many as 6,000 plus*. He and Anne Curry, Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at Southampton University, were the conceptual team behind the new museum and their research puts the number at around a more realistic 1,000 of which 534 – and they are quite specific on this number – were noblemen.

The English, by contrast, lost around 400 men (mostly archers) including just two noblemen.

The new museum is designed to explain the context, characters and details of the Battle of Agincourt using modern, often digital, displays that a young generation will recognise & engage with. It’s clever because it allows visitors to superficially skip through topics if they want, or dig down into a subject as deep as they want to go.

For example, Prof Curry, set Christophe Gillot and his team a challenge: explain the 100 Years War in 100 seconds! Their AV presentation does just that. Whether you’ll remember all the details afterwards is unlikely, but you will get a sense of how long, how complicated, and how many different factions were involved!

The museum is laid out so that there are two galleries separated by a 360° cinematic presentation of the battle itself.

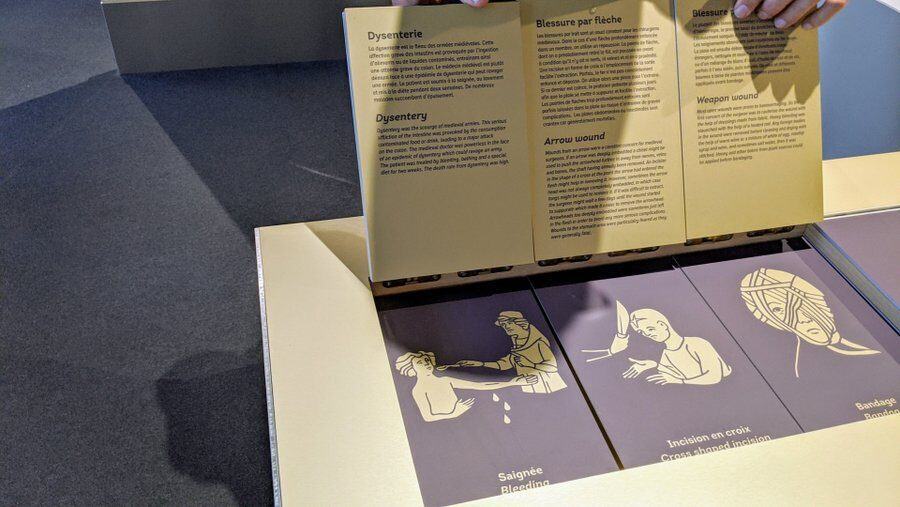

In the first gallery there are displays that cover the history, politics and culture of the period, such as food, dress, religion, medicine, etc.

Again, many of these topics are explained using interactive digital displays, such as the one covering medieval siege weapons.

The second gallery focuses on weapons, armour and equipment used at the Battle of Agincourt.

There are movie clips from the famous films of the battle, an explanatory video of a knight dressing himself in armour, and a rather scary interpretation of what it is like to be at the receiving end of repeated volleys of arrows.

To draw kids and families in, there is a display where you can physically test the strength required to draw a longbow, lift a sword, and wind a crossbow. Not easy!

Agincourt – The Battlefield

The Centre Azincourt 1415 is in the village of Agincourt itself. The battlefield is now wide open fields between Agincourt and Tramecourt with roads around the edge (see map above).

Sadly the all-important woods that so constricted the French army have long gone, but it is still worth seeing. You can drive (15 min) around or walk it (1hr 15min), and there are some viewpoints along the way.

* The estimates of the numbers and makeup in the English and French armies differ from historian to historian, as do the numbers of dead & captured. There’s a summary of their calculations, including Anne Curry’s, in the Wikipedia account of the battle.

¹ Agincourt – Christopher Hibbert, Windrush Press 1995.

Declaration: I was on a self-driving press trip as a guest of Nord-pas-de-Calais Tourisme. Museum entry was complementary.

Factbox

Website:

Centre Azincourt 1415

Getting there:

Centre Azincourt 1415

24 rue Charles VI

62310 AZINCOURT

France

Just over an hour’s drive south from Calais. (According to Google Maps it would have taken Henry and his men 14 hrs 22 mins!)

Entry Price:

| Adult | € 9.00 |

| Child (age 5+) | € 6.00 |

| Students, job seekers, journalists. | € 7.50 |

| Family (2 adults + 2 children) | € 25.00 + € 2 per extra child |

Opening Hours:

Open all year, every day except Tuesdays from 10 am to 6.30 pm. Last entry: 5.30 pm.