A new exhibition featuring 23 exotic clockwork treasures beloved by Chinese emperors, and loaned from The Palace Museum in Beijing, opened this week at the Science Museum in London.

The magnificent 18th century automata, called Zimingzhong 凝时聚珍: meaning ‘self-sounding bells’ or ‘bells that ring themselves’, combine timekeeping, music, and movement in a display of amazing craftsmanship.

These are not Chinese clocks. These are clocks made by British clockmakers to be given as trade gifts to Chinese emperors and dignitaries. They played an important role in facilitating early cultural exchanges. Some of the first zimingzhong to enter the Forbidden City were brought by missionaries in the early 1600s, seeking to ingratiate themselves in Chinese society by presenting beautiful gifts to the emperor. Decades later, the Kangxi Emperor (1662-1722) began collecting the automata which he christened ‘zimingzhong’, displaying them as ‘foreign curiosities’ and demonstrating his mastery of time, the heavens and his divine right to rule.

Visitors begin their journey with the ornate Pagoda Zimingzhong, a celebration of the technology and design possibilities of zimingzhong.

The unique piece, over 1m tall, dates from the 1700s and was made in London during the Qing Dynasty in China. The complex moving mechanism is brought to life in an accompanying video which shows the nine delicate tiers slowly rise and fall.

Whilst the demand for Chinese goods was high, British merchants were keen to develop their own export trade and British-made luxury goods like zimingzhong provided the perfect opportunity to do so. This exchange of goods led to an exchange of skills. In the Mechanics section of the exhibition visitors can see pieces like the Zimingzhong with mechanical lotus flowers, which was constructed using both Chinese and European technology.

When the clockwork is wound, a flock of miniature birds swim on a glistening pond as potted lotus flowers open. The sumptuous decorative elements are powered by a mechanism made in China while the musical mechanism was made in Europe.

The Making section of the exhibition explores the artistic skills and techniques needed to create zimingzhong. On display together for the first time are the Temple zimingzhong made by key British maker, James Upjohn, in the 1760s and his memoir which provides rich insight into the work involved in creating its ornate figurines and delicate gold filigree.

The Making section also has four interactive clockwork mechanisms, created by Hong Kong Science Museum, that illustrate the technologies used to operate the zimingzhongs’ complex movement and create their musical accompaniment. Skilled engineers designed sophisticated gearing and programmers would convert written musical scores into mechanisms. This for example is an elegant petal dome movement.

One of the curious aspects of the zimingzhong is that they were mostly designed for the Chinese market by craftsmen who had never travelled to Asia. So they often reflect British perceptions of Chinese culture in the 1700s. A classic example is the Zimingzhong with Turbaned Figure, which mixes imagery associated with China, Japan and India – a generalised European view of an imagined East, reflecting the ‘chinoiserie’ style that was popular in Britain at the time. It highlights British people’s interest in China but also their lack of cultural understanding.

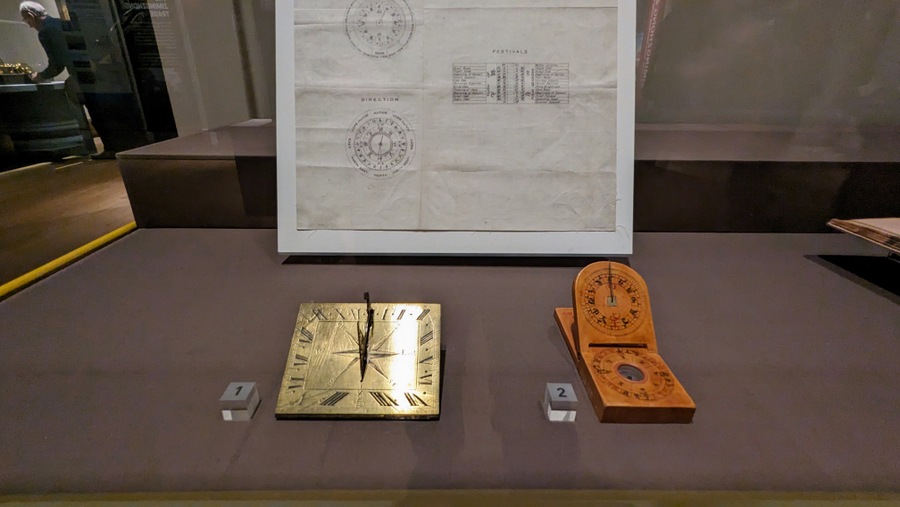

Although beautiful to behold, zimingzhong weren’t purely decorative. They were functional too, in a society that had relied principally on weather-dependent sundials for keeping track of time. As timekeepers, they had a variety of uses, including organising the Imperial household and improving the timing of celestial events such as eclipses. Accompanying the clocks is a publication from 1809 written by Chaojun Xu and on loan from the Needham Research Institute, titled 自鸣钟表图说 (Illustrated Account of Zimingzhong). The document was used as a guide for converting the Roman numerals used on European clocks into the Chinese system of 12 double-hours, 时 (shi) .

Launching the exhibition, Jane Desborough, Keeper of Science Collections at the Science Museum, said: “I hope visitors enjoy exploring these intriguing and detailed works of art and can also marvel at the technological skill and mechanisms behind each zimingzhong. Timepieces like the zimingzhong with a crane carrying a pavilion* represent a very special meeting of cultures and technology – its intricate mechanism was made by British maker and retailer, James Cox, but the delicate outer casing and beautiful decorations were almost certainly made in China.”

And not all the clocks were made by British clockmakers… there were Chinese knock-offs too! The Qianlong Emperor often asked his craftsmen to copy existing zimingzhong. This example with cheap materials like paste gems looks like a zimingzhong made by London clockmaker James Williamson, until you notice his name printed back to front and upside down on the dial!

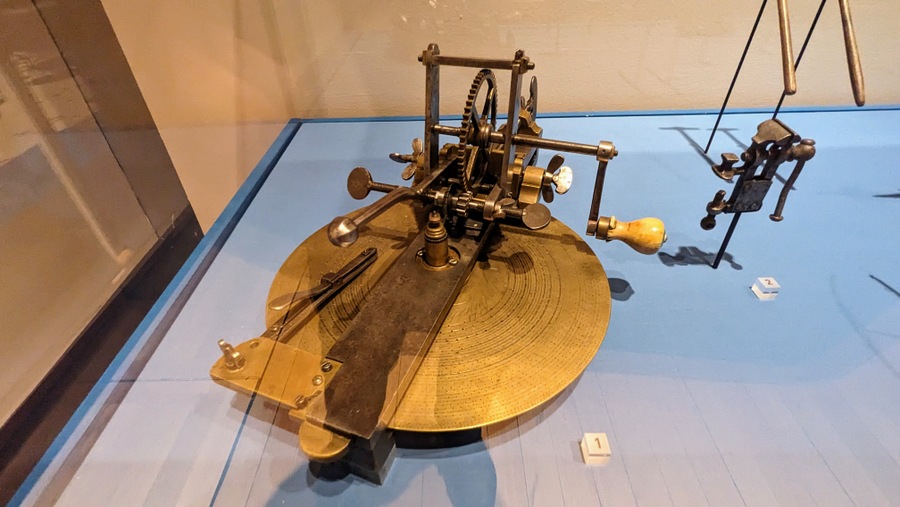

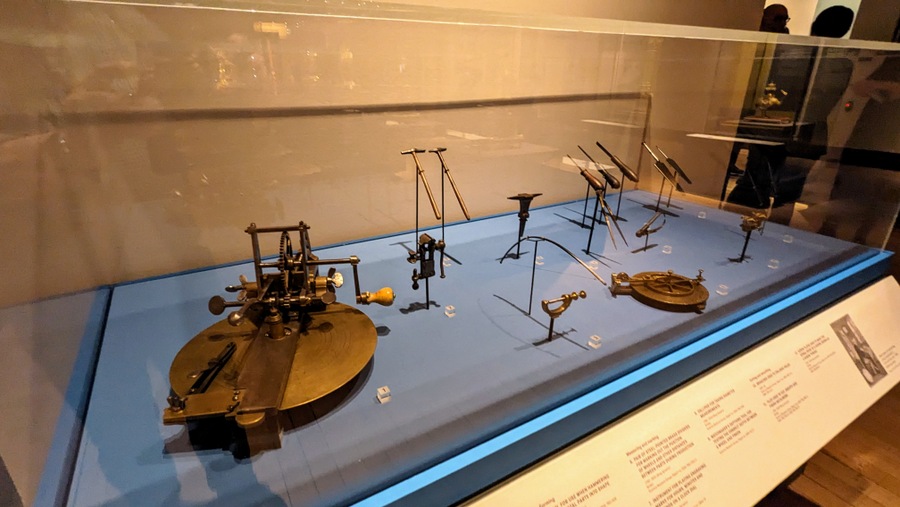

Visitors can also see rare books and archival material from the Science Museum Group Collection, including Louis Le Comte’s account of his visit to China; a clock made by one of London’s leading clockmakers, George Graham; an analemmatic sundial made by the talented mathematical instrument maker, Thomas Tuttell (See pocket sundials above); and a selection of hand tools from James Watts’ workshop.

The tools are fascinating in themselves.

By the way, I’m not sure item No. 2, the clockmakers clamp in the background, is all that rare. I have one floating around in my toolbox at home!

Ok, time to ask me which was my favourite zimingzhong…?

Well, it’s the completely over the top rural setting. They call it: ‘Zimingzhong with moving countryside scene’. I call it the ‘homestead zimingzhong’ It’s fabulous and I’d just love to see it moving. (None of the zimingzhong move any longer. They are just too old and delicate.) The Homestead zimingzhong’s complex mechanism, hidden away in the base, plays music, moves scenery, turns glass rods to look like moving water, and animates no less than 13 animals!

Eventually the zimingzhong trade began to decline after 1796, when Emperor Jiaqing ascended the throne; he believed zimingzhong to be a frivolous waste of money and the trade faded. But zimingzhong continued to be used by China’s elite class and highlighted the growing global links being forged by trade.

The Zimingzhong 凝时聚珍: Clockwork Treasures from China’s Forbidden City exhibition runs until Sunday 2 June 2024. The public are invited to pay what they can to visit the exhibition, with a minimum ticket cost of £1.00 per person.

* looks more like an emu to me!